International Holocaust Remembrance Day marks the liberation of the infamous Auschwitz death camp 71 years ago.

As Germany’s dwindling survivors of Nazi death camps mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day Wednesday, they and younger members of the nation’s Jewish community are fearful of a new tide of anti-Semitism driven by old hatred and a new influx of Muslim refugees.

Commemoration of the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the camp in Poland where 1.1 million Jews were murdered, is always a somber event, but on the 71st anniversary current events have cast a new and dark shadow. Waves of refugees from countries where hatred of Jews is taught and practiced have flooded Germany, prompting some of the nation’s 100,000-strong community to fear for their future.

“There are growing anxieties in the Jewish communities about a potential rise in anti-Semitism and the security of Jewish life,” said Deidre Berger, director of the American Jewish Committee’s Berlin office.

“There are growing anxieties in the Jewish communities about a potential rise in anti-Semitism and the security of Jewish life.”

Berger and others note anti-Semitism has persisted for decades among the extremist fringe, which ironically is gaining strength in reaction to the Muslim influx. While Germany has long condemned the Nazi regime and the genocide it carried out, the flame of deadly prejudice was never fully extinguished.

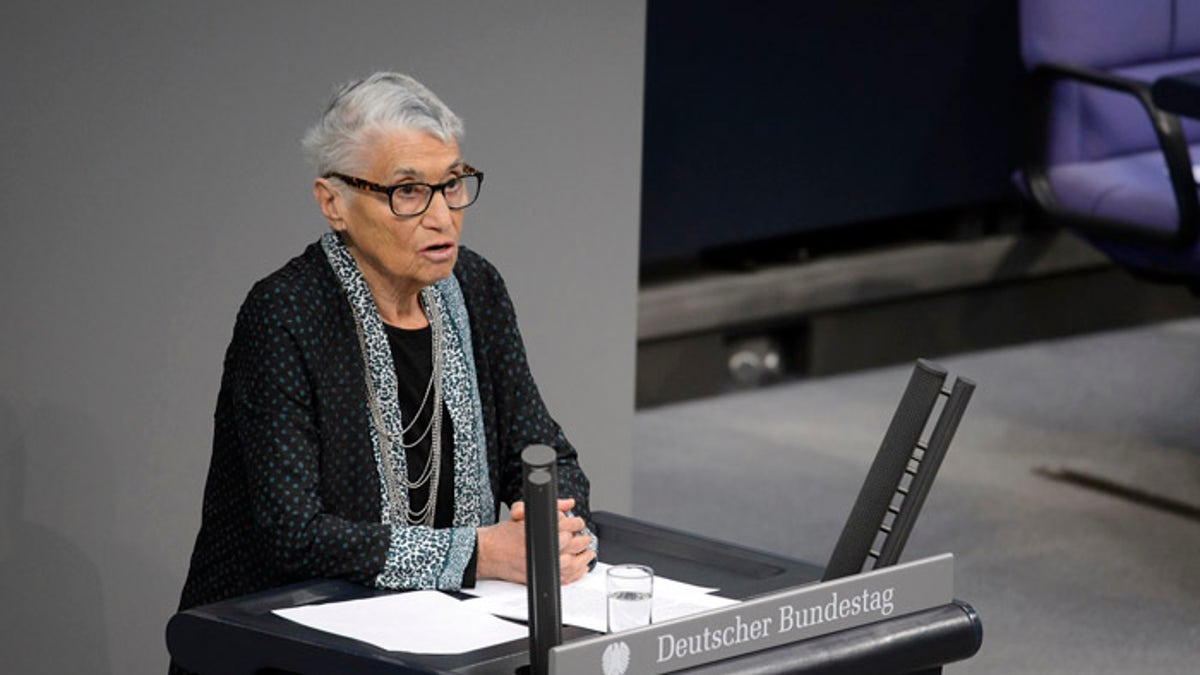

Ruth Kluger's story of survival in the Holocaust gripped German leaders Wednesday. (German Federal Government/Marvin Güngör)

“After the Holocaust, only the explicit manifestations of anti-Semitism vanished, but the thoughts did not disappear,” said Monika Schwarz Friesel, a professor of linguistics at the Technical University in Berlin and an authority on anti-Semitism.

On Wednesday, Ruth Kluger, 84, a Holocaust survivor, addressed the German Bundestag with a chilling reminder of Germany’s Nazi past. She said she is alive today only because a stranger told her to lie about her age and say she was 15 instead of just 12. To her Nazi tormentors, the age difference meant she could work and was worth keeping alive.

German officials Stanislaw Tillich, Joachim Gauck and Chancellor Angela Merkel greet Holocaust survivor Ruth Kluger after she adressed the German Bundestag Wednesday. (German Federal Government/Marvin Güngör)

“The lie was whispered to me from a friendly writer two minutes before; she was a prisoner like me, and I just bravely repeated it,” Kluger recalled. “The SS man looked at me and said that I would be very small. The writer claimed boldly that I had strong legs, ‘Look at her, she can work.’

“He shrugged his shoulders and accepted it,” Kluger continued. “I owe my life to a coincidence of few minutes and to a kind young woman, who I saw only once in my life. The rest of the transport to Theresienstadt that I arrived with was gassed in the next days.”

Such haunting memories have long been passed on to new generations of German Jews as a means of honoring their past and safeguarding their future. But now, some leaders are concerned that some of the more than 1 million Muslim refugees that Germany accepted last year are anti-Semitic. This week, the centrist newspaper, Der Tagesspiegel, published articles about two Jews who are debating whether to leave Germany.

“Some of this hatred from refugees comes from young people who come from countries where hatred for Jews is widespread,” Chancellor Angela Merkel warned earlier this month, adding that the new wave of anti-Semitism “must be dealt with urgently, and “has no place in German society.”

A German expert has similar concerns.

“Most Middle Eastern and African countries have fostered fervent anti-Semitism,” said Professor Wolfgang Bock, an expert on national security at the Federal Academy for Security Policy. “A large part of the Muslims living in European nations harbor deep-seated anti-Semitism as well.”

A report in Tuesday’s Die Welt, a leading German newspaper, indicated that anti-Semitic graffiti was seen by a visitor to Berlin’s Tempelhof airport, which is now being used to house refugees seeking asylum in Germany.

Die Welt reported that an Israeli Jew, wearing a skullcap, saw maps of the Middle East with Israel absorbed by its Arab neighbors. The visitor also saw a swastika and a Star of David next to 666, which represents the devil.

There’s been widespread criticism of Merkel’s open-door policy for refugees fleeing war zones, which Merkel asserts is Germany’s obligation given its own role in creating so many refugees generations ago. Opponents say the country can’t house and school the staggering influx of refugees, especially given their different cultural and religious backgrounds.

“If the chancellor, who said the security of Israel is the raison d’etre of German policy, pursues a refugee policy that makes Jews anxious or threatened, this would be a great blow to her policy,” Malte Lehming, opinion editor of Der Tagesspiegel, told FoxNews.com.

Lehming said Jews are leaving France because of anti-Semitism.

“If the Jews start leaving Germany for the same reason, that would be the end of the chancellor’s government.”

Norbert Lammert, the leader of the Bundestag, told the legislature when it marked the liberation of Auschwitz in 2011 that 20 percent of Germans harbored anti-Semitic sentiments. The number came from a study sponsored by the German government.

“That is 20 percent more than we should have in Germany,” Lammert said at the time.

Four years later, many Germans, including members of the Jewish community, fear a Europe-wide trend could mean the figure is rising.