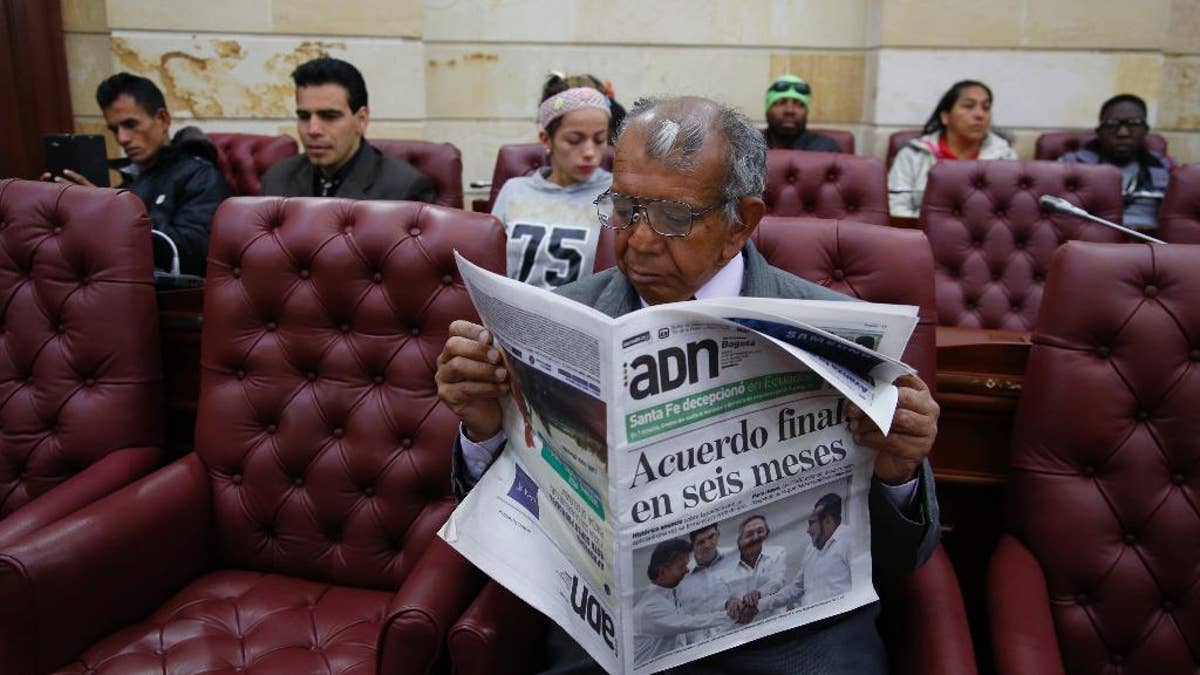

Pedro Osuna Ramirez, 67, who says that he and his family were pushed from their land in central Colombia by rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC, reads a newspaper during a hearing with victims of the guerrilla group inside Congress in Bogota, Colombia, Thursday, Sept. 24, 2015. Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos and leaders of the FARC met in Havana on Wednesday, and vowed to end Latin America's longest-running armed conflict in the coming months. The newspaper's headline reads in Spanish "Final agreement in six months." (AP Photo/Fernando Vergara) (The Associated Press)

HAVANA – President Juan Manuel Santos and leaders of Colombia's largest rebel group vowed to end Latin America's longest-running armed conflict in the coming months after reaching a breakthrough in talks that put the country closer to peace that it has been in half a century.

Speaking in Havana, where talks between the sides had been dragging on for years, Santos announced on Wednesday that government and rebel negotiators, prodded by Pope Francis to not let a historic opportunity for peace slip away, had set a six-month deadline to sign a final agreement. After that, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia would demobilize within 60 days.

"We are on different sides but today we advance in the same direction, in the most noble direction a society can take, which is toward peace," said Santos, minutes before a forced, cold-faced handshake with the military commander of the FARC, known by his alias Timochenko.

The U.S. government lauded the breakthrough, with Secretary of State John Kerry saying that "peace is now ever closer for the Colombian people and millions of conflict victims."

In a joint statement, Santos and the FARC rebels said they had overcome the last significant obstacle to a peace deal by settling on a formula to punish human rights abuses committed during about 50 years of bloody, drug-fueled fighting. The formula is designed to demand accountability from belligerents while insulating a deal against possible legal challenges from victims.

Under the terms reached, rebels that confess abuses to special peace tribunals, compensate victims and promise not to take up arms again will receive from 5 to a maximum 8 years of labor under unspecified conditions of confinement but not prisons. War crimes committed by Colombia's military will also be judged by the tribunals and combatants caught lying will face penalties of up to 20 years in jail.

While a final accord may be within reach, the huge challenges of implementing it are just beginning. Negotiators must still come up with a mechanism for rebels to demobilize and then the government needs to come up with additional money to spread the benefits of peace in parts of Colombia's vast, jungled countryside that have known little else than war and where the state's presence is almost nil.

A more immediate test will come in the form of a referendum, in which Colombians will get a chance to endorse or reject any deal, which must also clear congress. Foreshadowing what's likely to be a bitter political fight, conservative former President Alvaro Uribe lashed out at the Wednesday's agreement, calling it a gift to the FARC and Venezuela's "tyranny," even before details were known.

"The government accepts that the criminals aren't going to jail," said Uribe, whose military offensive last decade winnowed the FARC's ranks and pushed its leaders to the negotiating table. "This is a bad example for society that will generate more violence."

Wednesday's agreement was reached after a week of frenzied negotiations away from the klieg lights of Havana at the Bogota apartment of a former president of Colombia's constitutional court, two of the six lawyers involved in the talks told The Associated Press.

Negotiators said the surprise advance came as rebels rushed to demonstrate progress ahead of a visit this week to Cuba by Pope Francis, who during his stay on the communist-led island warned the two sides that they didn't have the option of failing in their best chance at peace in decades.

"Without even being present physically in the room he was a very important presence," said Douglass Cassel, a University of Notre Dame law professor who represented the government in the talks.

The sticking point was what would happen if the FARC lied to special tribunals and guarantees that the rebels wouldn't be extradited to the U.S., where they face charges for cocaine trafficking, if they honored their commitments, according to Cassel. The breakthrough came during a marathon 20-hour negotiating session last Thursday that wrapped up at 5:30 a.m. just three hours before the FARC's advisers were on a flight to Havana to get the commanders' blessing.

In the end negotiators fell just short of receiving the pope's blessing but advanced faster and further than anyone could've imagined.

"It's satisfying to us that this special jurisdiction for the peace has been designed for everyone involved in the conflict, combatants and non-combatants, and not just one of the parties," Timochenko, whose real names is Rodrigo Londono, said in a statement.

As part of talks in Cuba, both sides had already agreed on plans for land reform, political participation for guerrillas who lay down their weapons and how to jointly combat drug trafficking. Further cementing expectations of a deal, the FARC declared a unilateral cease-fire in July.

But amid the slow but steady progress, one issue had seemed almost insurmountable: How to compensate victims and punish FARC commanders for human rights abuses in light of international conventions Colombia has signed and almost unanimous public rejection of the rebels.

The FARC, whose troops have thinned to an estimated 6,400 from a peak of 21,000 in 2002, have long insisted they haven't committed any crimes and aren't abandoning the battlefield only to end up behind bars. They say that they would only consent to jail time if leaders of Colombia's military, which has a litany of war crimes to its name, and the nation's political elite are locked up as well.

The government has gone to great lengths to insist that its framework for so-called transitional justice doesn't represent impunity for guerrilla crimes such as the kidnapping of civilians, forced recruitment of child soldiers and sexual violence. Only lesser crimes such as rebellion will be amnestied.

But Human Rights Watch said it was difficult to imagine how the provisions for justice could survive a review from Colombia's constitutional court and the International Criminal Court if those who committed abuses don't spend a single day in prison.

Supporters, however, are optimistic it can withstand the myriad of challenges.

"The most important court the agreement will face is the court of public opinion in Colombia," said Bernard Aronson, President Barack Obama's special envoy to the Colombian peace process. "There's a tremendous longing for peace after 50 years of war and I'd be surprised a final settlement didn't receive support."

___

Goodman reported from Bogota, Colombia. AP Writers Jacobo Garcia, Libardo Cardona and Cesar Garcia contributed to this report from Bogota.

___

Follow Goodman on Twitter: https://twitter.com/apjoshgoodman