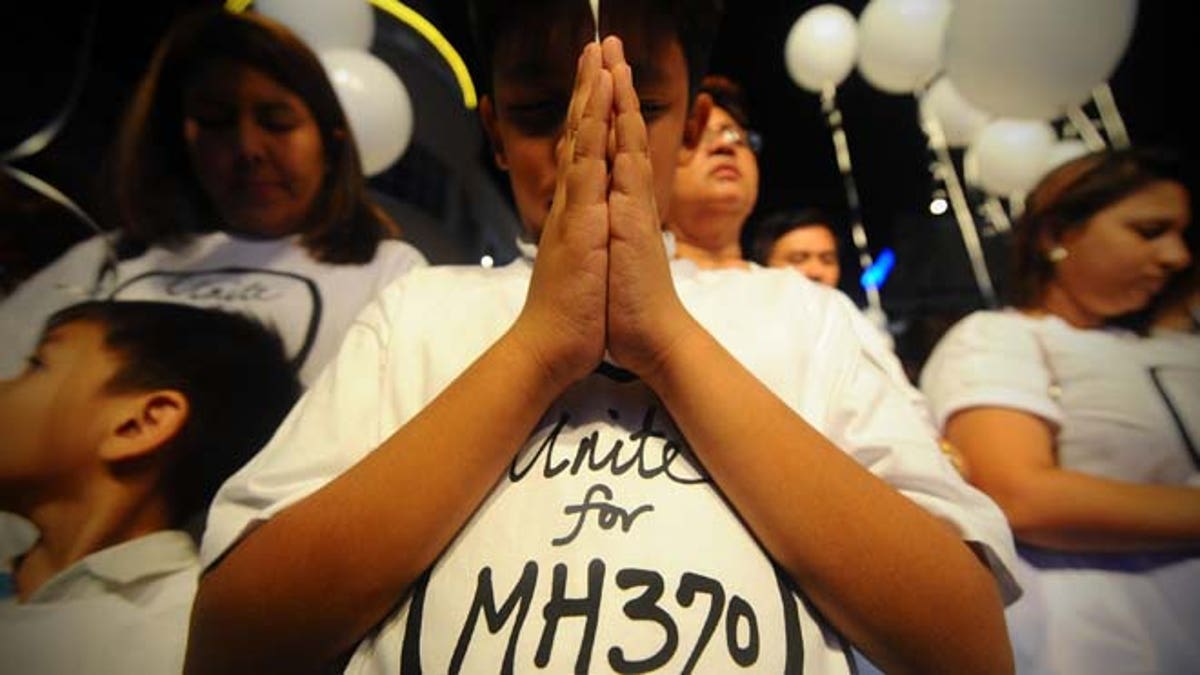

March 18, 2014: A young Malaysian boy prays at an event for the missing Malaysia Airline Flight 370 at a shopping mall in Petaling Jaya on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. (AP)

SYDNEY – After a four-month hiatus, the hunt for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is about to resume in a desolate stretch of the Indian Ocean, with searchers lowering new equipment deep beneath the waves in a bid to finally solve one of the world's most perplexing aviation mysteries.

The GO Phoenix, the first of three ships that will spend up to a year hunting for the wreckage far off Australia's west coast, is expected to arrive in the search zone Sunday, though weather could delay its progress. Crews will use sonar, video cameras and jet fuel sensors to scour the water for any trace of the Boeing 777, which disappeared March 8 during a flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing with 239 people on board.

The search has been on hold for months so crews could map the seabed in the search zone, about 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles) west of Australia. The 60,000-square kilometer (23,000-square mile) search area lies along what is known as the "seventh arc" — a stretch of ocean where investigators believe the aircraft ran out of fuel and crashed, based largely on an analysis of transmissions between the plane and a satellite.

Given that the hunt has already been peppered with false alarms — from underwater signals wrongly thought to be from the plane's black boxes to possible debris fields that turned out to be trash — officials are keen to temper expectations.

"We're cautiously optimistic; cautious because of all the technical and other challenges we've got, but optimistic because we're confident in the analysis," said Martin Dolan, chief commissioner of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, the agency leading the search. "But it's just a very big area that we're looking at."

That area was largely unknown to scientists before the mapping process began in May. Two ships have been surveying the seabed using on-board multibeam sonar devices, similar to a fish-finder. The equipment sends out a series of signals that determine the shape and hardness of the terrain below, allowing officials to create three-dimensional maps of the seabed.

Those maps are considered crucial to the search effort because the seafloor is riddled with deep crevasses, mountains and volcanoes, which could prove disastrous to the pricey, delicate search equipment that will be towed just 100 meters (330 feet) above the seabed. Two of the search ships will be using underwater search vessels worth around $1.5 million each.

"You can imagine if you're towing a device close to the seafloor, you want to know if you're about to run into a mountain," said Stuart Minchin, chief of the environmental geoscience division at Geoscience Australia, which has been analyzing the mapping data.

The terrain isn't the only challenge. The area is prone to brutal weather, and is so remote that it takes vessels up to six days to get there from Australia. Water depths are also tricky: They range from 600 meters (2,000 feet) to 6.5 kilometers (4 miles). That's about the deepest the sonar equipment can go, Dolan said.

"In all sorts of ways we're operating towards the limits of the technology that is available," Dolan said.

With the mapping nearly complete, the GO Phoenix, provided by Malaysia's government, will begin hunting in an area considered the likeliest crash site, based on an analysis of satellite data gleaned from the plane's jet engine transmitter and a series of unanswered phone calls officials on the ground made to the plane.

The other two vessels, the Equator and Discovery, provided by Dutch contractor Fugro, are expected to join the hunt later this month.

Malaysia and Australia are each contributing around $60 million to fund the search.

The ships will use towfish, underwater vessels equipped with sonar that create images of the ocean floor. The towfish, which transmit data in real time, are dragged slowly through the water by thick cables up to 10 kilometers (6 miles) long. If something of interest is spotted on the sonar, the towfish will be hauled up and fitted with a video camera, then lowered back down.

The towfish are also equipped with sensors that can detect the presence of jet fuel, although that would likely be a longshot.

David Gallo, who helped lead the search for Air France Flight 447 after it crashed in the Atlantic Ocean in 2009, said that even if the fuel tanks had survived the impact, strong currents in the search area probably would have dispersed any leaking fuel by now. Still, he said, it's worth a try.

"In some of the steep rugged areas any kind of additional information would be useful to help peer into the dark shadows," Gallo, an oceanographer with the U.S.-based Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, said in an e-mail.

There will be between 25 and 35 people on each ship, and crews will likely work around the clock. The ships can stay at the search site for up to 30 days before they must head back to shore to refuel and resupply.

"The most efficient way is to keep going," Dolan said. "But you have to be careful with the well-being of your crews, to be sure you're not pushing them too hard."

The work will be painstaking. The ships can move no faster than 11 kph (7 mph) while towing the sonar equipment. If a vessel needs to change direction, the crew must first pull the towfish up enough that it won't fall to the seafloor during the turn — a process that takes hours.

"None of this happens very quickly," Dolan said.

Irene Burrows, whose son Rodney Burrows was on board Flight 370 with his wife, Mary, believes the plane will be found. Not knowing her son's fate has made moving forward a near impossibility.

"We're in limbo," she said. "It will be good to know where it is — I think that's what is important to all the family."

Search officials are acutely aware of the sentiment.

"We're doing this primarily because there are families of 239 people who deserve an answer," Dolan said. "We will give it every possible effort and we think our efforts will be really good — but there's no guarantee of success."