Why ISIS may be more dangerous than Al Qaeda

Insight from the Heritage Foundation's Peter Brookes

Syria’s bloody civil war has spawned a separate rift with ramifications well beyond the region known as the Levant -- a battle for the very soul of the global jihad movement.

Islamic militants who poured into the embattled nation to help the Free Syrian Army in its bid to topple dictator Bashar Assad are now fighting Assad, the rebels and each other in a barbaric free-for-all. At the center is the split between Al Qaeda’s regional affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, and the newly emerged Islamic State, which are fighting each other on the battlefield and in the war for recruits to the cause of Islamic terrorism.

“The two groups are now in an open war for supremacy of the global jihadist movement,” according to Middle East scholar Aaron Zelin in a research paper published by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a U.S.-based think tank.

Throw in the jihadist-led insurgency in neighboring Iraq, which has become intertwined in the insurrection in Syria, and the shifting alliances are becoming for many even harder to understand.

[pullquote]

Last week, Al-Nusra, struggling to stay relevant and recruit fighters, released a video featuring three of their fighters as they head off in northern Syria near the city of Aleppo to battle the Islamic State, which was disowned by Al Qaeda. The message was that they, not Islamic State, have the purer motives.

“We in the Al Nusra Front only fight to raise the word of Allah, to make the oppressed triumphant,” one fighter says. “We only fight to get rid of the enemy Bashar and his soldiers. We have come to fight them so that we can impose Allah’s laws on the country. We have not come to oppress people, steal from people, or take their property.”

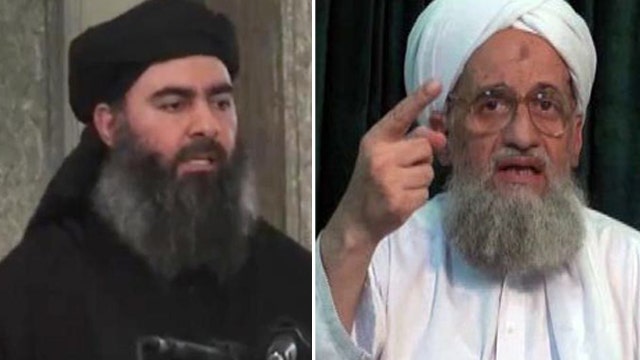

Another fighter urges Islamic State fighters to defect and “return to the truth” by joining Al Nusra, which is aligned with several Islamist rebel militias in Syria and has been fighting against the Islamic State since last winter, when Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri disavowed Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the boss of the upstart group then known as ISIS.

“Al Qaeda announces that it does not link itself with [ISIS] ... It is not a branch of the Al Qaeda group, does not have an organizational relationship with it and [Al Qaeda] is not the group responsible for their actions,” the terror network’s General Command declared.

The pointed disavowal sparked mass defections from Al Baghdadi’s burgeoning operation. Jihadist and rebel groups eager to avenge ISIS assassinations of their comrades, took it as a sign it was open season on ISIS.

But Al Baghdadi, whose mentor was Abu Mousab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian militant who himself was rebuked in 2005 by Al Zawahiri for excessive extremism in Iraq, clawed back. The success Islamic State, as it is now known, has enjoyed since is testament to his leadership skills and strategic savvy of the jihadist veterans from Iraq and Chechnya who are at the core of ISIS. By forming alliances with Sunni tribes along the border and deep into Iraq, Al Baghdadi managed to magnify his power.

Some terror experts believe Al Zawahiri, Usama bin Laden’s successor as Al Qaeda chief, was too slow in identifying Al Baghdadi as a serious rival for leadership of the global jihad movement. Tensions had existed within the jihadist movement in Syria since April 2013, the year before the disavowal, and “core Al Qaeda failed to take a genuinely commanding line,” said Charles Lister, a terrorism expert with the think tank Brookings Doha Center.

Some analysts view the split as having been prompted by Al Qaeda’s leadership fear that Al Baghdadi was too cruel with his beheadings, beatings and whippings and imposition of religious Shariah law on territory his men controlled.

But the dispute is, in some ways, more of a generational difference and a vying for the loyalty of jihadists affiliates and offshoots around the world – a jostling that is fracturing the jihadist movement and represents the biggest challenge Al Qaeda has faced since U.S. Navy SEALs took out bin Laden.

Many of the younger generation of jihadists support the Al Baghdadi idea of seizing territory and carving out a jihadist caliphate. They want their own state and have tired of Al Qaeda’s traditional approach of gradualism.

Caliphate refers to a system of government stretching across most of the Middle East and Turkey that ended nearly a century ago with the fall of the Ottomans.

And Al Baghdadi has been smart in his marketing – outshining Al Nusra in the use of social media to recruit and message.

“Taken globally, the younger generation of the jihadist community is becoming more and more supportive, largely out of fealty to its slick and proven capacity for attaining rapid results through brutality,” Lister said.

Al Baghdadi’s announcement of a caliphate in the summer straddling the border of Syria and Iraq – he has ambitions to spread it all the way west to Lebanon -- has increased his standing among jihadi groups worldwide and more foreign fighters are choosing to join him than Al Nusra.

Several important affiliates have sworn allegiance to ISIS, while many others are avoiding declaring their choice between al Baghdadi or Al Qaeda, preferring to hedge their bets and wait to see who comes out on top.

On the ground in Syria and Iraq, the top dog at the moment is ISIS. With the advanced weaponry it has captured from fleeing Iraqi forces and the money it looted from Iraq’s regional banks, it has taken over the group and has much to offer recruits.

But Islamic State’s expansion has brought new battlefronts that could stretch the terror group to the breaking point. In Iraq, where it has carried out horrific executions of Christians and other religious minorities, it now faces hardened Kurdish fighters, the Iraqi Army, U.S. airstrikes and a budding international coalition and even Iran.

All that comes even as Islamic State, estimated to include less than 20,000 fighters, continues to seize villages and kill enemies in Syria. If the well-funded upstart terror group hopes to stay on top of the global jihad movement, it will have to maintain its momentum.