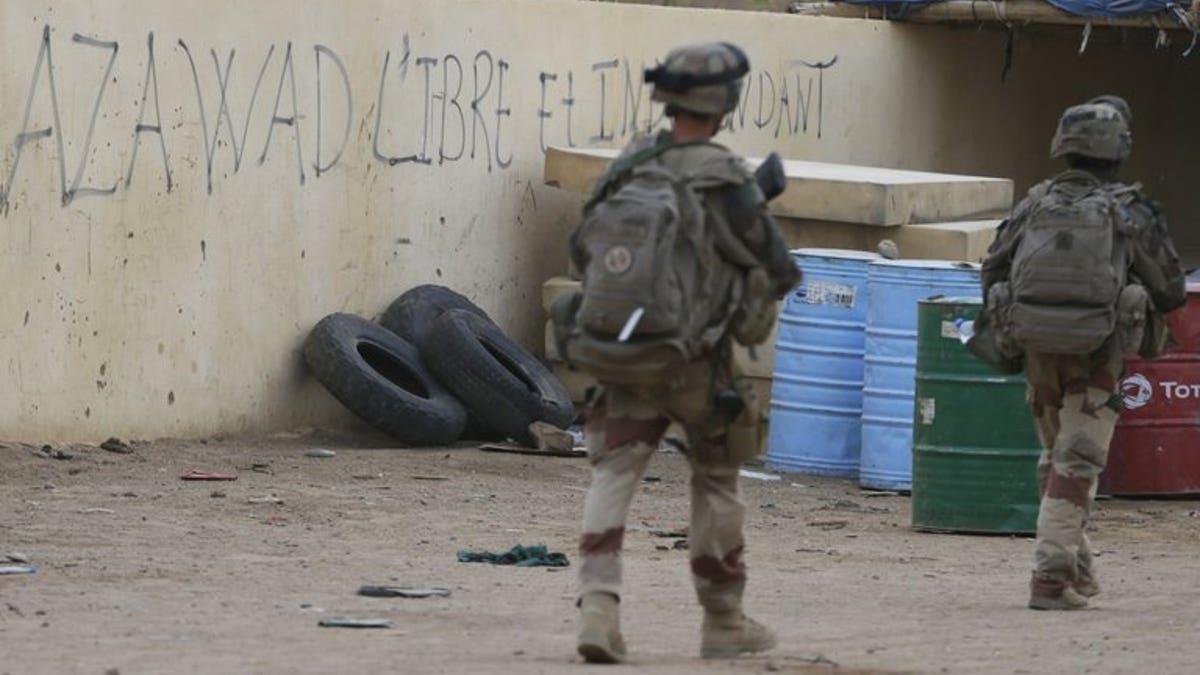

French soldiers walk past a graffito that reads "Azawad free and independent" as they patrol on July 27, in Kidal, Mali. On the eve of Mali's watershed presidential election, the authorities in the rebel bastion of Kidal were confident Saturday of well-run polls, although they were under no illusions about getting a big turn-out. (AFP)

KIDAL, Mali (AFP) – On the eve of Mali's watershed presidential election, the authorities in the rebel bastion of Kidal were confident Saturday of well-run polls, although they were under no illusions about getting a big turn-out.

There was no evidence on dusty, sun-baked streets of the remote desert settlement that polls seen as pivotal to conflict-scarred Mali's future were less than 24 hours away -- no campaign posters or slogans, no Malian flags even. "There was no campaign here," said one resident. One emblem, however, was ubiquitous: the four-colour flag of Azawad, the name Tuareg separatists give to northern Mali.

Graffiti on the walls of Kidal, 1,500 km (930 miles) northeast of Bamako, proclaims: "We are not Malians." "I am responsible for organising the elections, I am not responsible for delivering the voters," smiled Kidal governor Adama Kamissoko, who has temporarily abandoned his army colonel's uniform and wears a "Mali elections 2013" cap.

"But at least 13,000 voter cards have been distributed within a fortnight in the Kidal region, which is very encouraging." Kidal has 35,000 people on the electoral roll, a drop in the ocean when seen in terms of the seven million voters registered nationwide. But well-run polls in the settlement, near the Algerian border, are vital for the credibility of the elections nationwide.

Kidal, the cultural stronghold of the Tuareg people and the historic birthplace of their most influential clans, is also something of a powder-keg.

The region, also called Kidal, has been marginalised by successive administrations since Mali gained independence and the town has been the centre of various Tuareg uprisings.

A kidnapping of five election officials in the Kidal region last week was blamed on the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a rebel group founded to fight for independence for Mali's minority Tuareg.

The election is considered vital to the future of Mali which is battling to restore democracy after an 18-month crisis that saw it suffer a Tuareg rebellion, a military coup and the seizure of more than half its territory by Islamist extremists.

The MNLA took control of Kidal in February after a French-led military intervention ousted Al Qaeda-linked fighters who had piggybacked on the Tuareg rebellion to take control of most of northern Mali then chase out their former MNLA allies and impose a brutal form of Islamic law.

The Malian authorities finally reclaimed the city after signing a ceasefire deal with the MNLA on June 18 in Burkina Faso's capital, Ouagadougou.

The kidnappings came after violence between the lighter-skinned Tuaregs and Mali's majority black population rocked Kidal earlier this month, leaving four people dead, businesses looted and ransacked and the city's central market burned.

Meanwhile observers have increasingly cast doubt on whether Kidal will be ready for the election.

One of 28 presidential candidates, Tiebile Drame, dropped out of the race ahead of the election saying the country was not prepared, especially Kidal.

"This election is a political Caesarean section, an abnormal birth that makes the mother suffer. But that doesn't mean that it generates a stillborn child," said Ambeiry Ag Rhisa, acting secretary-general of the MNLA. "But it is necessary for Azawad and Mali to establish an agreement that recognises Azawad with its own personality and acceptable governance, which leaves us to manage our business by ourselves."

Aliou Zeimi, 18, who will vote for the first time on Sunday, said he was backing Dramane Dembele of Adema, Mali's largest party, as he picked up his voting card at his former school, which has been vandalised and closed for more than a year. "These are the bandits of Azawad who did this. It is important to vote for our country, we want peace. We want to take back our country," said Zeimi, a member of Kidal's black community.

If the MNLA's official line is to back the election, this position has nothing like unanimous support among the rank-and-file.

Many Tuareg do not feel a "Mali" election has anything to do with them, a little over a year after their brief proclamation of independence for Azawad.

"I am a member of MNLA but I am against the Ouagadougou agreements, like everyone else here. We respect them because we gave our word, but not the Malians, they haven't released a single prisoner," said Aminatou Walet Bibi.

The activist, who has organised several demonstrations by women against the return of the Malian government and soldiers to Kidal, said her people would "rise up again" if the Azawad issue was not resolved. "We have no water and no electricity but we do not need it if it comes from Mali. If Mali is staying here, I'd rather die.

"My father died in the revolution against France, my uncle took part in the revolt in the 60s, my brother in the 90s... My son will be another revolutionary. Until we are liberated from Mali, it will be revolution, generation after generation." thm/stb/ft/lc