BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – A new project is documenting the history of LGBTQ people in the Deep South, a region that once all but forced gays, lesbians and others to live in hiding.

Bob Burns, who is gay, both lived through some of the toughest times for LGBTQ Southerners and documented them through years of activism. Now 66, he compiled a trove of information from years that included the AIDS epidemic and the systemic oppression of gay people in the Deep South.

Burns is now among the donors to a nonprofit organization that's gathering information about the hidden history of gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, transgender people and others in the Southern United States.

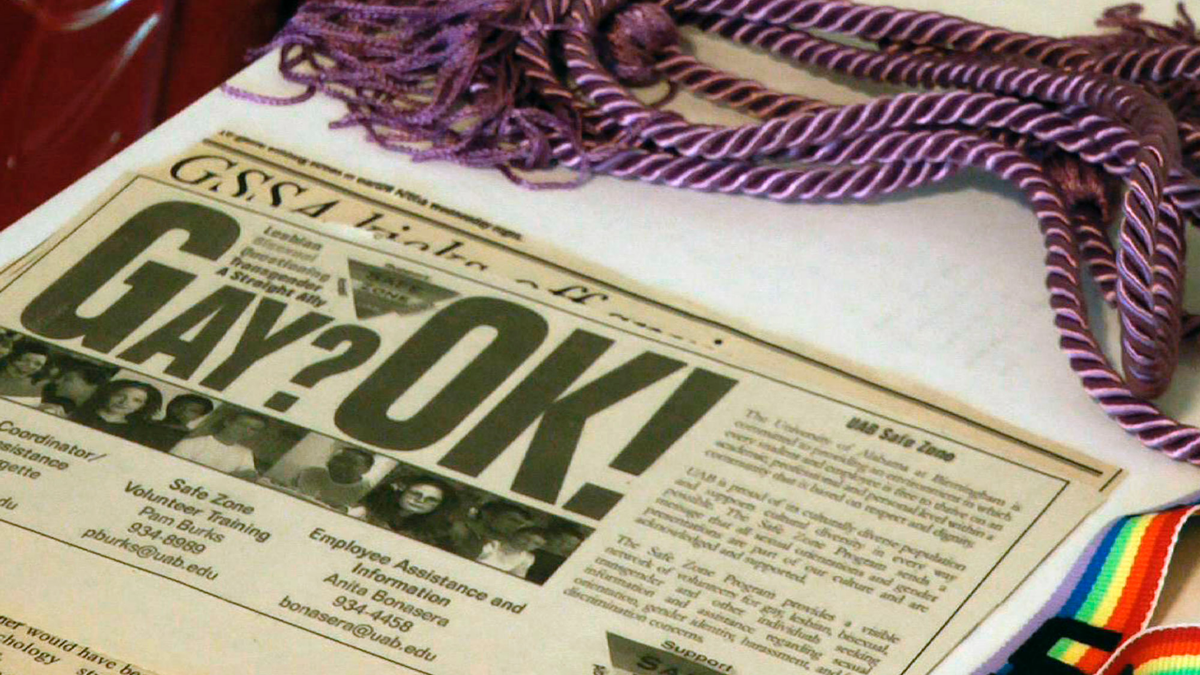

Established in late 2016, the Birmingham-based Invisible Histories Project already has gathered boxes full of information about gay life in Alabama, including decades-old directories of gay-friendly businesses dating to the late 1960s; activist T-shirts; records from gay-rights groups; and rainbow-themed material.

The organization will expand its work to Mississippi and Georgia later this year, and organizers hope to cover the entire Southeast within a few years.

The Stonewall National Museum and Archives in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, has thousands of books and artifacts documenting LGBT cultural and social history across the nation, and the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco tells the story of the Bay Area community. The History Project does the same in Boston for New England gays.

Historian and archivist Joshua Burford said the goal of the Invisible Histories Project is to create a uniquely Southern collection that will "give Southern history back to queer Southerners."

While the stereotypical LGBTQ person might live openly in an urban center and have plenty of money, he said, plenty of Southern gays live both in cities and in rural areas where they hold working-class jobs.

"If the model is always the West Village or Boy's Town or Fire Island, then the South can never be the same as that. So we have to stop pretending like we want to be," said Burford, engagement director of the group. "What we are is very queer and very Southern, and those two things are always overlapping."

Items in the collection include documents about a conflict over plans to hold the Southeastern Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual College Conference at the University of Alabama in 1996. U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Alabama's attorney general at the time, unsuccessfully argued that holding the event at a public university conflicted with a state law then in effect, prohibiting homosexual acts.

The meeting went ahead as planned without incident, and Alabama voters elected Sessions to the U.S. Senate later that year.

The archive also includes documents related to the arrest of about 20 men accused of cruising for gay sex in a weeklong police sting conducted in a park in Tuscaloosa in 2002, said Burford, who originally researched the cases for school and is giving personal materials to the project.

Rather than developing a mammoth, gay version of the Smithsonian Institution that could be difficult for people to visit, the Invisible Histories Project plans to store items in smaller, local repositories. Much of the Alabama archive is housed at Birmingham's main public library.

"We want to make sure that people who really care and are most affected by the materials can access it easily," said development director Maigen Sullivan. "So we're working with a number of smaller institutions that are closer to the community so that we can store their things there."

Burns, a prominent architect, likes the idea.

After hearing about the project through a friend, he met with Burford and donated items including the results of lengthy surveys he helped compile in 1989 and again in 1999 documenting what he called almost continual discrimination and rights violations directed at LGBTQ people in Alabama.

"That all had been sitting in a trunk here because there was no one to give it to," said Burns, who has lived in Birmingham nearly 40 years.

He also donated a report compiled following a daylong event held years ago at a gay-friendly church to assess the needs and desire of the gay community around Birmingham.

"There was no place for that information to go so it was basically wasted," he said. "But at least now it's part of history. We know what people in whatever year it was, 15 or 20 years ago, thought was important."

Burford said it's important to document the past accurately because LGBTQ people have been lied about and disregarded for generations.

"Queer people are orphaned from American history," he said.