NH leads nation in overdoses from deadly drug Fentanyl

New Hampshire leads nation in overdoses from deadly drug Fentanyl.

PLAISTOW, N.H. – On an autumn afternoon in 2014, Jim Zanfagna received a phone call from his son-in-law, alerting him to a string of alarming messages that were surfacing on Facebook.

His 25-year-old daughter, Jacqueline, had died, and friends were posting condolence messages before the Zanfagnas ever heard from authorities.

“Social media learned before we did,” Zanfagna said, as he fought back tears inside his Plaistow, N.H., home.

The cause of death was an accidental overdose from heroin laced with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that is killing more people in New Hampshire than in any other state.

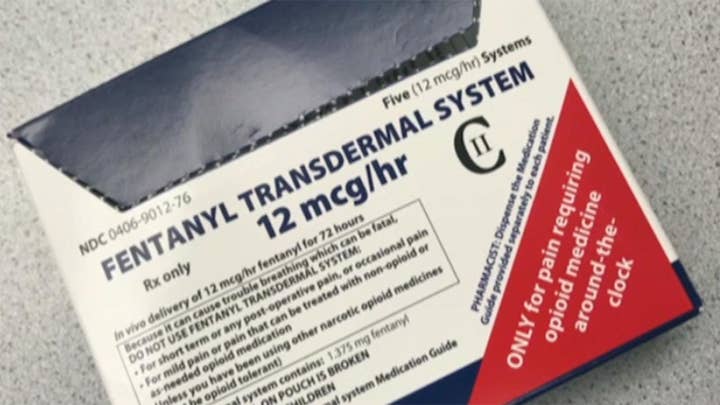

Fentanyl is deadly at two milligrams – akin to a few grains of salt – making the risk of a fatal overdose high. While the drug is commonly used by hospitals, it is also made illicitly in China and imported into the U.S. by Mexican drug cartels.

“Fentanyl is extremely powerful and was intended mainly for use in anesthesia and postoperative pain control,” said Dr. William Goodman, medical director at the Catholic Medical Center in Manchester.

“One thing that makes abusing street drugs so dangerous is that quality control is very poor,” Goodman told Fox News. “You may get a chunk of white stuff with a lot of fentanyl and it takes very little to kill you.”

For Jim Zanfagna, trouble began shortly after his wife, Anne Marie, was prescribed Vicodin – a widely-used narcotic drug – to relieve her debilitating knee pain. One day, Zanfagna said she noticed a depleted supply of pills and confronted her daughter about it.

“I would always ask Jackie and she would say, ‘No,’” Zanfagna said.

Before long, it was obvious to the family that their daughter was addicted to the pain killers.

“I stopped her from leaving the house with a bottle of it – a big bottle of it. And she said, ‘You’re choking me’ and I guess I was but I couldn’t let her take it,” Zanfagna recalled.

Jacqueline Zanfagna’s drug use would later progress from prescription opioids to heroin. So strong was her addiction that the young woman would often steal her mother’s jewelry and sell it at a nearby pawn shop to get cash, according to her family.

Zanfagna’s story is a sad representation of the nation’s opioid crisis – an epidemic that does not discriminate based on age, race, income level or location.

“We know that the people using street drugs – illicit opioids – four out of five started with prescription pills,” said Goodman. “Either they had them prescribed directly or they’re using diverted pills. And often what leads them to go from pills to injection of fentanyl or heroin is that it’s easier to get. You don’t need a prescription and it’s often much less expensive.”

“In the 1960s, most people abusing heroin started with heroin – not pills,” Goodman said. “Now that’s changed. First-time users start with pills, then go to heroin, as opposed to the past when they started with the injection drugs.”

In 2016, there were more than 20,000 deaths in the U.S. related to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The three states with the highest rates of death due to drug overdose are West Virginia, Ohio and New Hampshire.

Daniel Goonan, the Manchester city fire chief, said firefighters routinely carry Narcan -- a life-saving anti-overdose drug which also goes by the generic name naloxone -- when responding to the scene of an overdose. It takes just a tiny amount of fentanyl or its derivatives, which can be inhaled or absorbed through the skin or mucus membranes, to result in an overdose – making it dangerous for anyone who comes across it, including first responders.

“We don’t have a heroin problem in New Hampshire. We have a fentanyl problem. It’s almost all fentanyl,” Goonan said. “I don’t know how to describe the death that we’re seeing here as a community. It’s mind-boggling.”

After the death of her youngest daughter, Anne Marie Zanfagna, a talented artist, channeled her grief by painting faces of the opioid crisis – 120 victims to date from all over the country.

“The first portrait I painted was Jackie,” Zanfagna said as she sat in front of an easel in the art studio of her home. “I spent two months painting it. It was like spending time with her. There was joy and there was sorrow.”

After showing the colorful oil painting of her daughter to a support group, Zanfagna said she received requests from other families. She soon started a non-profit, called “Angels of Addictions,” to make portraits for people who had lost loved ones to opioids.

“The families are amazed by them. They feel that their son or daughter is not forgotten,” she said. “And when you see the portraits all together, it is extremely powerful. It shows you that this is a tragedy that can happen to anyone.”