US school districts are hiring more foreign educators

Teachers come here to educate American students in a number of subjects on a J-1 cultural exchange visa

LAS VEGAS – Adrian Calabano, 23, left his native Philippines to fill a void of teachers in a Nevada suburb. He said he sold his car to pay for his flight and hefty administrative fees so he could get a salary several times higher than he would receive in his homeland.

But his salary is still lower than an average American teacher. He was hired to teach sixth grade special education class at Greenspun Junior High School in Henderson, Nev., a suburb of Las Vegas.

“My salary is much better than what I receive and get from the Philippines,” he told Fox News.

As debate over low teacher salaries makes its way across the country – there have been statewide protests in at least four states the past two months – this little-known U.S. program for foreign teachers is growing.

U.S. school districts are increasingly hiring teachers from abroad to fill a dearth of teacher in school districts across the country. They are brought in through a cultural exchange visa program offered by the U.S. State Department. Known as the J-1 visa, it is the ticket for teachers abroad to come to the U.S. and teach American students.

Adrian Calabano, 23, readies his classroom. Filipino and here on a J-1 visa, he teaches sixth grade special education at a junior high school outside Las Vegas. (Fox News)

But the program has come under heavy criticism by educators who feel it is depressing already low teacher wages and displacing America educators who would earn higher wages.

Because the foreign teacher is working on a visa considered a “cultural exchange,” the district does not have to offer them the perks and benefits a regular teacher would get. States increasingly using the program to hire teachers include Arizona, California, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Nevada.

There were 2,867 J-1 visa holders placed in U.S. schools in 2017, up from about 1,197 in 2010, according to the U.S. State Department. The J-1 visa is temporary, lasting about two to three years.

Critics say the foreign teachers don’t hold the same credentials as local educators and are a legal loophole for districts to pay even lower teacher salaries. Plus, critics say, it’s not solving the overall issue – teacher shortages.

"It's just putting a Band-aid on a huge gaping wound,” said Michelle Kim, a spokesperson for the Clark County Education Association, the local teacher's union. “What kind of message is the district sending? They can solve the issue if they were to prioritize and compensate educators that they have.”

Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, the largest union for educators in the country, said the visas are not in the best interest of teachers. She calls the program an “abuse of an exchange program.”

“Every classroom in America needs a well-supported, well-trained, well-paid educator helping students learn and thrive,” Weingarten said. “Teachers fight every day for the resources to do their job, and we fight for and with them — that includes solving shortages by improving wages and working conditions and giving teachers the professional respect, voice and latitude they need to succeed.”

Calabano acknowledges that he and his other fellow Filipino colleagues have come under criticism.

“I’ve heard some complaints from my other Filipino teachers, I mean, from my friends, that some American teachers, they think we’re incompetent, especially in speaking English,” he said. “For some parents, I’ve heard some of my friends, they told me that some parents are hard to deal with. I’m not sure if it’s because of their kids or if it relates to our country.”

Supporters say the foreign teachers are filling a critical need – and it benefits everyone who takes part in the program.

“It’s a mutually beneficial program that brings experienced foreign teachers with specialized training and education into American classrooms,” said James Bell, president of Alliance Abroad, which sponsors many foreign teachers. “U.S. children receive bilingual teaching experiences, learn about other cultures and countries, and benefit from the teachers’ expertise in areas such as special education, STEM education and foreign language.”

This is all taking place among a fraught political background as U.S. teachers are solidifying their political might. This year, thousands of educators have organized walkouts of their classrooms, temporarily paralyzed school districts and amassed in multitudes at their state capitols to demand higher wages, more school resources and to renegotiate their pensions and benefits.

States like Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and West Virginia have, for the most part, conceded to teachers’ pleas, avoiding protracted battles between legislators and unions by agreeing to give educators raises and investing more tax dollars in schools.

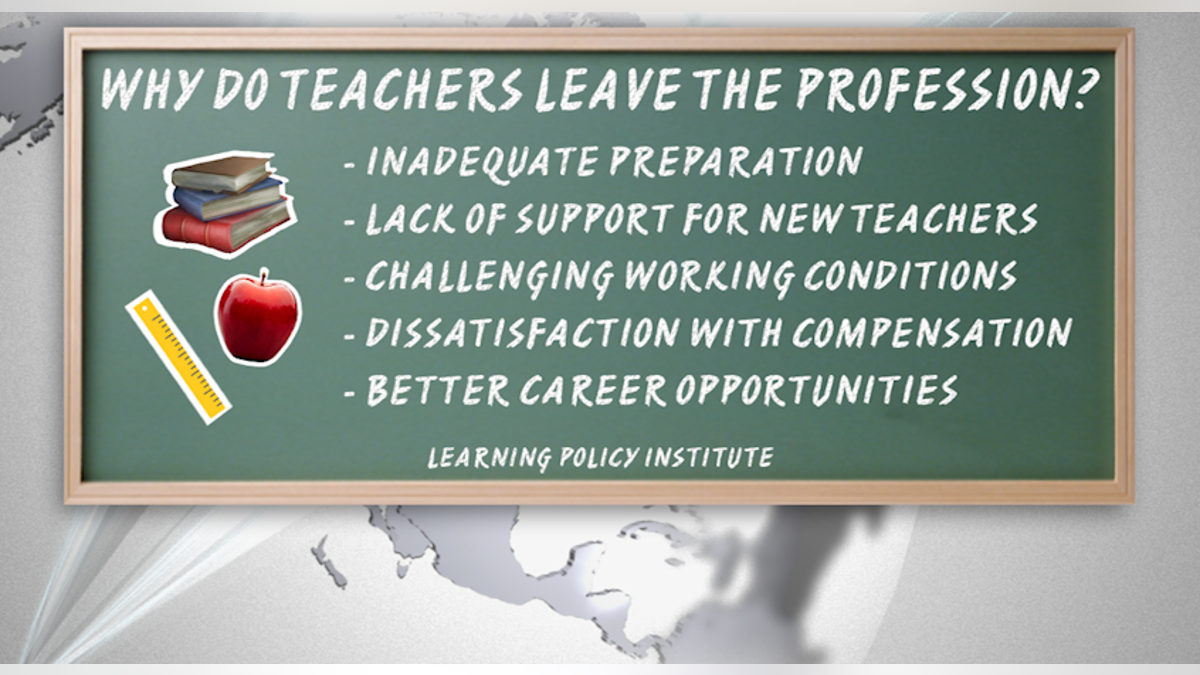

And, amid all this democratic noise, every state in the country for the 2017-2018 school year was experiencing a teacher shortage, according to the Learning Policy Institute, an education think tank that compiles such data.

Data compiled by education think tank Learning Policy Institute show why U.S. teachers leave the profession. (Fox News)

In Clark County, Nev., Calabano and about 80 Filipinos were hired by the Clark County School District to teach special education. As the fifth largest district in the nation, it employs approximately 18,000 teachers.

For Calabano and those teachers wanting to come here, the visa application process is lengthy, costly, and has a number of requirements.

Would-be visa holders need to have a sufficient level of proficiency in English and are required to have been a teacher and must have been teaching in their country of origin for at least two years. Many nonprofits work in tandem and sponsor applicants for a fee to help them get recruited to teach in U.S. schools.

The J-1 visa goes beyond teachers, also including au pairs, camp counselors and foreign exchange students, professors or researchers.

For some school districts, it is a critical lifeline for districts dealing with severe teacher shortages.

“The district uses the J-1 Visa program as part of its recruiting program. Due to the extreme shortage of teachers in Arizona and the United States, we work on every aspect of recruiting to obtain teachers but it is virtually impossible to fill the number of teachers needed with candidates who are U.S. citizens. This is a temporary, legal way for the district to hire teachers and provides a cultural diversity our schools need and want,” said Nedda Shafir, a spokesperson for the Pendergast Elementary School District in Phoenix.

Shafir disputes the notion that her district is prioritizing international teachers over U.S. citizens. Since 2015, around 50 foreign teachers have been hired out 500. Shafir said the hires take place not instead of, but in addition to, American hires.

Once the visa expires, the foreign teacher musts return home. They cannot request to return to the U.S. for two years.

Calabano said he has learned a lot and wishes he could extend the visa.

“For me I want to stay, but I’m required to go back to the Philippines, for a certain time,” he said. “Long term, if I can get a working visa, I would love that.”