Behind the scenes of rescue task force training

Drills teach first responders to work in tandem as police and medics train to work together in emergencies; Laura Ingle reports from Poughkeepsie, New York.

Imagine being a paramedic or firefighter trying to save the life of someone who has been shot, or badly injured while you are under the threat of being shot yourself. It sounds like a scene from a battlefield overseas, but it has become a reality for many paramedics and firefighters working to bring medical aid to victims during active shooter situations.

In most cases, law enforcement agencies find themselves in a position to hold EMTs back until a scene is declared safe or "cold" to help prevent further injuries or deaths.

In recent mass shootings like the one in Parkland, Fla. at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where 17 people were killed and many others wounded and waiting for help, some paramedics reported being frustrated after they were told they couldn't go into the school because law enforcement feared the situation was still "hot," or active.

In recent mass shootings like the one in Parkland, Fla. at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where 17 people were killed and many others wounded and waiting for help, some paramedics reported being frustrated after they were told they couldn't go into the school because law enforcement feared the situation was still "hot," or active. (AP)

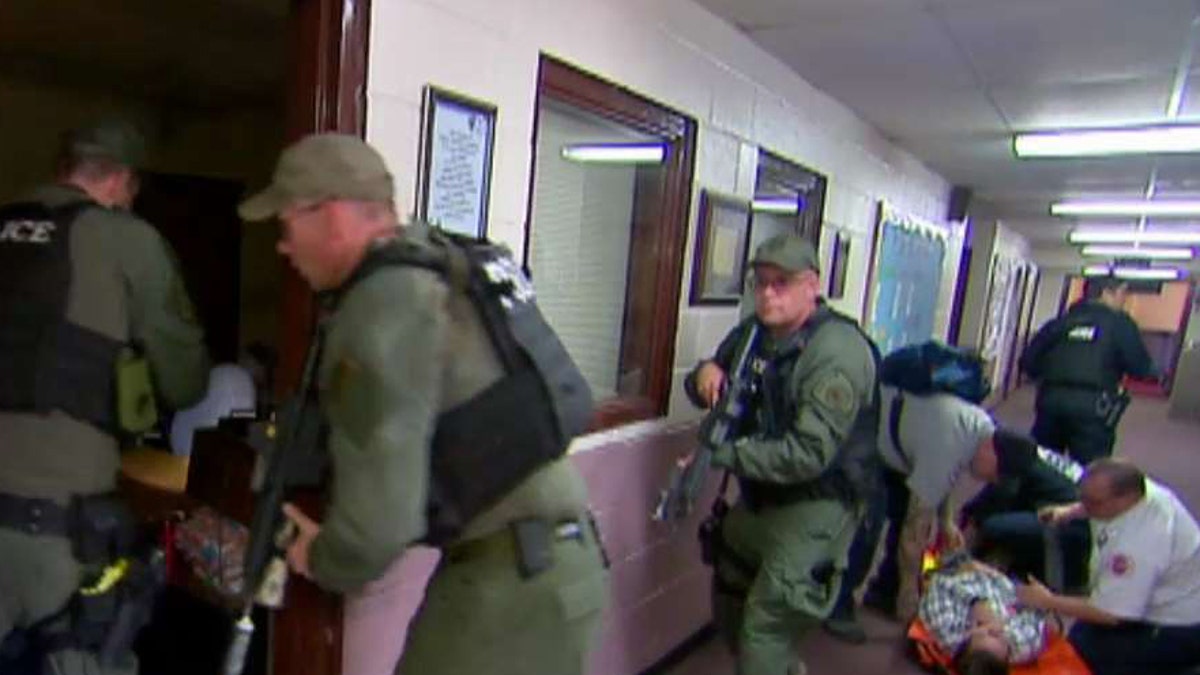

Scenarios like the one in Florida have encouraged many Rescue Task Force teams across the country to ramp up the frequency of training. The goal: To help law enforcement and paramedics coordinate efforts to quickly get into an area that emergency personnel call the "warm zone" during hyper violent events, when police are present and the danger level has dropped.

Chris Strattner with the National Center for Security and Preparedness at the University at Albany's College of Emergency Preparedness and Homeland Security and Cybersecurity, recently ran a training operation in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. with EMS, firefighters and law enforcement inside and outside an unused church and school.

Strattner told Fox News there's a lot of good work these teams can do in the warm zone.

"That warm zone is where we think that paramedics or firefighters who have good training can move into that space. Firefighters are all brave guys. They're used to going into burning buildings, they're used to going into wrecked cars,” Strattner said. “So we're just giving them the tools to go into another semi-safe place, we can tell them how to make it a little safer for themselves and let them work to save lives in that spot."

Paramedics learning the language and timed movements of armed entry has been going on nationwide for years, but intensified after the Columbine High School massacre in Colorado in 1999.

Sgt. Patrick Barry of the Poughkeepsie Police Department said running drills as often as possible is an important aspect of the Rescue Task Force.

Scenarios like the one in Florida have encouraged many Rescue Task Force teams across the country to ramp up the frequency of training. The goal: To help law enforcement and paramedics coordinate efforts to quickly get into an area that emergency personnel call the "warm zone" during hyper violent events, when police are present and the danger level has dropped. (AP)

"When it comes to training, especially with the fire department, it's important that we do it often so if the actual situation does happen, it goes flawlessly,” Barry said. “So we learn from these past experiences and try to improve ourselves."

Strattner said medical workers learn “tactical emergency causality care.”

“That's the idea of putting a tourniquet on early, not worrying if that tourniquet is going to cause someone to lose their arm, because it's not, using things like commercially prepared dressings that will help stop bleeding like QuikClot or Celox, and sealing holes in a chest,” Strattner said. “And if you can do those three things you're going to buy a whole lot of time for that person who might have died in 5 minutes. You might buy yourself 20 or 30 minutes, which gives you the time to get to the hospital to get to a surgeon."

Both the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, have issued guidelines for active shooter incidents, but there is not a federal mandate on how agencies should work in tandem.

Capt. Christopher Mills of the Arlington Fire District in Poughkeepsie says it's tough to be in a position where you want to help but you are not being allowed to do what you are trained to do.

In most cases, law enforcement agencies find themselves in a position to hold EMTs back until a scene is declared safe or "cold" to help prevent further injuries or deaths. But that protocol is now changing. (Fox News)

That’s why he hopes these ongoing drills will teach these teams how to gain safe access to the injured.

"It can be really frustrating. That's why it's important for us to continue this training, continue our partnerships, and continue to spread the word that this is probably the better way to do it than how they were doing it in previous years," Mills said.

Lt. Joe Tarquinio of the Arlington Fire District said it’s good to plan ahead and train for these situations – and frequently – before it’s too late.

"You need to have a game plan 5 minutes before as well as months before,” said Tarquinio, who recently took part in the Poughkeepsie Rescue Task Force training, “and that's the biggest part."