Ohio sues drugmakers over opioid epidemic

Attorney General Mike DeWine lays out case on 'America's Newsroom'

Last year, one Rust Belt county in southwestern Ohio saw 349 accidental deaths from opioid overdose – and things are getting worse.

Bodies are arriving at a dizzying, unyielding pace to the coroner’s office, showing the scale of the scourge that has hit Ohio harder than any other state in the nation.

No one in Montgomery County needs to rely on federal data to measure the viciousness of the opioid epidemic. As of June 1, the county had tallied 360 drug overdose deaths.

“At this pace, we expect about 800 overdose deaths by the end of 2017,” Ken Betz, director of the Montgomery County Coroner’s Office, said.

The county has been hit with so many overdose deaths that it even had to build an extension to its morgue last year to accommodate the soaring number of bodies.

The opioid epidemic has claimed lives across the entire socioeconomic spectrum in Ohio, which last year had more fatal drug overdoses than any other state, according to a county-by-county analysis by the Columbus Dispatch.

On Tuesday, the coroner’s office confirmed that an overdose of the synthetic opioid carfentanil – which is 10,000 more powerful than morphine -- and cocaine had caused the March deaths of a Spirit Airlines pilot, Brian Hayle, 36, and his wife, Courtney, 34. The couple was found in their home by their four children.

Statewide, more than 4,000 people died from drug overdoses last year. And in 2015, Ohio had the highest number of prescription opioid overdose deaths -- 1,800 -- of any state in the nation, according to the latest figures in an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

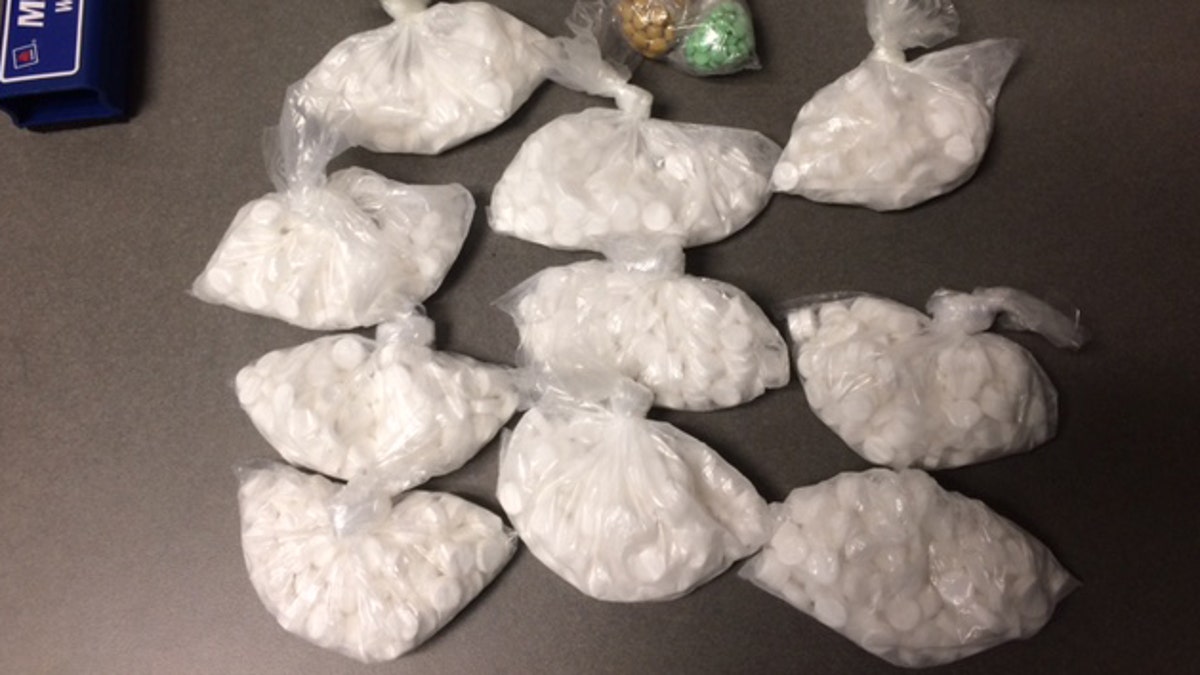

Drugs seized by Montgomery County (Ohio) Sheriff's officers (Montgomery Sheriff's Office)

Ohio state officials filed a lawsuit on Wednesday against the pharmaceutical industry over the opioid epidemic, accusing several drug companies of making a concerted effort to mislead doctors and patients about the dangers of addiction to painkillers and possible overdose.

If Montgomery County’s opioid death march continues unabated, the area will surpass Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland, and have the highest rate of overdose deaths in Ohio.

“The problem is getting worse every day,” said Montgomery Sheriff Phil Plummer, who has been so overwhelmed by the toll the epidemic has taken on his county that he personally has launched a multi-pronged fight against it. “We don’t have enough police resources to combat it. We work very hard, it’s changed our jobs.”

The world of opioids has gotten more encompassing and brazen, with Mexican cartels in Ohio not even bothering to mask their role or dodge authorities as they recruit local youth into their illicit trade, enticing them with money, among other things.

The epidemic, indeed, has produced “home-grown” gangs, ensnaring local youths and young adults and using them to supply neighborhoods with increasingly deadly drugs, Plummer said.

The sheriff and his officers have become social workers of a sort, Plummer said, while also bringing the full force of the law down on criminals who sustain and constantly seek to broaden the addiction to opioids and other drugs.

The sheriff and his officers are now driving people who have addictions to treatments centers. They are visiting their homes to try to rally family members to help address a relative’s addiction, and they are even hitting neighborhoods every Friday to go after dealers and to spread the word about the lethal consequences of opioids.

The problem is getting worse every day. We don’t have enough police resources to combat it. We work very hard, it’s changed our jobs.

On Thursday, they started what will be weekly visits to churches to raise awareness about opioids and the dangerous substances that are being mixed into them.

“We’re trying to be proactive,” Plummer said. “People say to us: ‘We didn’t know, we don’t understand’ the scope of the crisis.”

“I don’t know, with everything that’s out there, how some people still don’t know” about the epidemic.

The grip of the addiction is so intense that addicts are more and more brazen in where and when they smuggle and use the narcotics.

"They're overdosing in the jails and in courtrooms," Plummer said, adding that the demand for treatment is in such excess to the openings at facilities, that his jails have also become detox facilities.

Meanwhile, drug dealers and cartels always look for ways to get ahead of efforts by Plummer -- and others like him across the country – and often switch to other substances and methods for getting new buyers and getting them addicted, the sheriff said.

Consider this: People working for the cartels are now going to places such as gas stations and boldly approaching people to give them “samples” or “testers,” Plummer said, which are gel caps containing fentanyl or heroin (or both).

They provide these sample bags with, remarkably, business cards so that people can contact them if they want more.

"They're even doing car-to-car" drug deals, Plummer said, so that if they suspect police are approaching, they can just "take off in their car."

We've done so much, but the numbers are going the other way. I don't see the improvement.

William Denihan, the outgoing chief executive officer of the Cuyahoga County Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board, called the opioid epidemic a "tsunami."

"We've done so much, but the numbers are going the other way," Denihan said. "I don't see the improvement."

In Montgomery County, Plummer can relate.

"The frustration part," he said, given all that he and his officers are doing to address the issue from myriad angles, "is that things are just getting worse."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.