Santa Fe Japanese Internment Camp 75 years later

Japanese Americans were only allowed to take what they could carry when they were interned in camps during Word War II. 75 years later, they still carry painful memories that they're hoping society won't forget

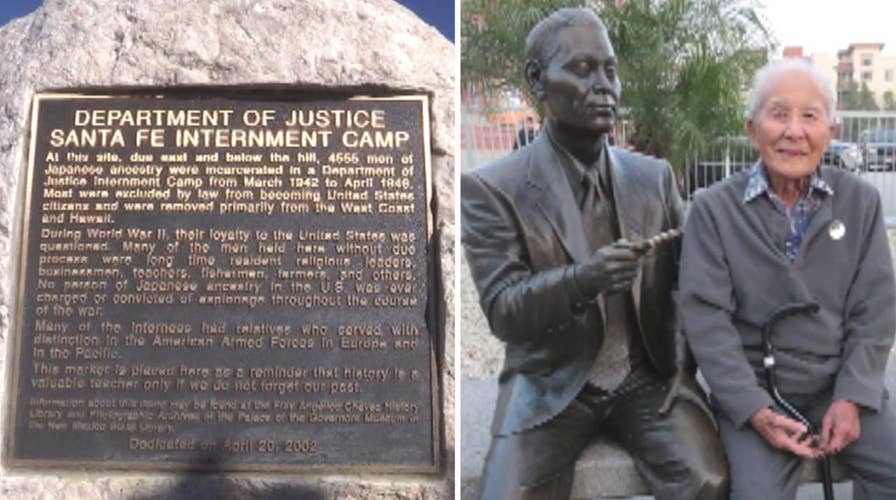

Bill Nishimura, 97, is not angry about the years he spent being sent from internment camp to internment camp.

"I lost everything, but I learned how to live," said Nishimura.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which relocated 117,000 people of Japanese descent to internment camps. 70,000 of them were American citizens. The order came two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. When the internees were taken to the camps, they could bring only what they could carry.

CALIFORNIA WWII VETERAN, CANCER SURVIVOR FACES EVICTION

Nishimura's father Tomio Nishimura was in five camps from February 1942 until June 1947 when he was released. Bill and his mother were first sent to a camp in Arizona on August 8, 1942. He also spent time at camps in Tule Lake, Calif., Crystal City, Texas, and Santa Fe, N.M., before he was released May 22nd, 1947.

Nishimura believes it was reasonable of the United States to incarcerate his father because he was a member of the Japanese Association, an organization that helps new immigrants make their way in society. However, Nishimura was incensed about his own incarceration because, unlike his parents, he was an American citizen. Nishimura had his citizenship taken away because he refused to answer loyalty questions on a questionnaire while his family was incarcerated. He got his citizenship back with the help of a lawyer in 1958.

COLORADO POLICE SEARCH FOR MISSING PURPLE HEART RECIPIENT

The government apologized on August 10, 1988. The "Restitution for World War II Internment of Japanese-Americans and Aleuts" acknowledged the wrongdoing of Executive Order 9066 and established a $1.6 billion trust fund for the families. The bill awarded each individual $20,000. Nishimura accepted the government's apology and said he hoped the internment camps would not be forgotten.

"I believe this story should be continued on," said Nishimura. "So that it will not happen again."

The first internees arrived to the all-male camp in Santa Fe in March 1942. In all, 4,555 prisoners would come in and out until April of 1946. Many of the men were U.S. citizens born and raised in America and some had sons who served with distinction in Europe and the Pacific. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, made up of Japanese Americans, was the highest decorated combat team of World War II.

"They fought the Germans in Italy and their units were slaughtered. They went in to rescue the lost battalion and the Texas Battalion and their units were decimated. But they fought hard, were highly honored and they got lots of Purple Hearts," said Nancy Bartlit, author of the book Silent Voices of World War II.

The internees were held without due process. As Bartlit explained, the government thought they posed a threat during wartime, simply because they were Japanese.

"This was a camp for men who could possibly be spies, who never were spies. But by virtue of them being of Japanese descent living in America, and being of a country who was at war with us, they were technically dangerous enemy aliens," said Bartlit.

Bartlit has spent years researching the internment camps. Throughout the course of her research she has become good friends with the Nishimura's.

The Santa Fe internment camp is gone and a neighborhood on the northwest side of town remains. A stone marker with a plaque sits on top of a hill to remember it. Former Santa Fe Mayor Larry Delgado cast the tie-breaking vote to place the marker near the site of the old camp. He believes the camp should not be forgotten.

"Some people want to say was it right, was it wrong? I don't know. There's strong feelings on both sides I'm sure. But basically it did happen, it was history," said Delgado.

According to Delgado, the vote for the marker was controversial because some people in the Santa Fe area were veterans of the Bataan Death March and had an aversion to the Japanese. However, Delgado said after the marker was installed many people who initially disagreed with him said it was the right thing to do.

Bill Nishimura hasn't shared much about what he went through with his relatives, simply because he said they haven't asked. But Nishimura is happy to share his story with anyone who will listen. Overall, Nishimura said he was treated well in the camps. He believes he was fed well and had a decent place to sleep and was not mistreated by the guards, but adds he did complain from time to time. Nishimura takes great pride in volunteering, helping to run exercise regiments and classes in the camps. He said while in the camp, he would run an hour a day and study hard to keep his mind and body sharp. It worked.

In addition to being physically strong and mentally sharp, Nishimura has kept his sense of humor. He joked that his time in the Santa Fe internment camp was "torture" because "we missed the girls," Nishimura said with a laugh.