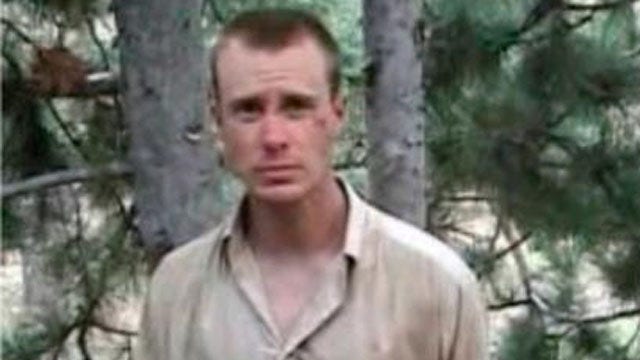

The announcement that the U.S. government had secured the release of missing U.S. Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl and that it was freeing five senior Taliban figures from Guantanamo Bay has been portrayed first and foremost as a prisoner exchange. But the four-year history of secret dialogue that led to Saturday's release suggests that the main goal of each side may have been far more sweeping.

It was about setting the stage for larger discussions on a future peaceful Afghanistan.

As The Associated Press first reported in 2011, talks about releasing the five senior Taliban reach back to at least late 2010, following nearly a decade of war. In the beginning, the name of Bergdahl, who was captured in mid-2009, was not even part of the equation.

The Taliban have sought a prisoner release from the beginning of their contacts with U.S. negotiators, while the U.S. side was looking for confidence-building gestures to keep the conversation going, with the ultimate aim of bringing hostilities in Afghanistan to an end.

In recent days, Republicans and some Democrats have been incensed about the release of the Guantanamo Five, warning that this will inspire other militants to target more Americans for abduction. They say the exchange was too hasty, without even a month's warning to Congress as the law requires. They also imply that the five are dangerous leaders who will quickly return to the battlefield and that it was too high a price to pay for a soldier who may have abandoned his post willfully and wandered into Taliban hands.

The Obama administration has justified its decision by saying there was an urgent need to retrieve Bergdahl from captivity and ensure his safety before most U.S. forces leave Afghanistan this year. Judging from the earlier stages of negotiations, the Guantanamo prisoners were not seen as critically important in their own right to retain as prisoners.

In the context of today's Afghanistan, the Guantanamo Five, while important figures, are not likely to change the balance of the war in any significant way. Although they held leadership positions, they weren't pivotal in policy decisions. And after having been away from Afghanistan for more than a decade, they are not likely to secure the loyalty of broad numbers of Taliban foot soldiers.

The five are Abdul Haq Wasiq, once the Taliban's deputy minister of intelligence, Mullah Norullah Nori, a former senior military commander, Khairullah Khairkhwa, a former governor of Herat, Mohammed Nabi, a former local security chief, and Mohamad Fazl, who allegedly presided over the mass killing of Shiite Muslims in 2000-2001. While some indeed were ruthless when in power, they were by no means considered the worst of the Taliban

As part of the deal, the emir of Qatar has guaranteed that all will be kept and monitored inside the small Gulf emirate for at least a year, meaning that they will be essentially isolated until after the bulk of U.S. forces have left Afghanistan.

For the U.S. side, getting Bergdahl back was hardly the main aim when the Obama administration first opened the door to negotiations with the Taliban.

In those early talks, the U.S. was seeking gestures of goodwill from the Taliban, such as a public declaration of the wish for peace. The talks, which went through Germany with help from Norway, appeared to be the first sign of forward movement.

In 2011, the names of the five detainees the Taliban wanted freed were already known, and the U.S. seemed amenable. U.S. officials were cautious, however, about bringing up Bergdahl's name.

But when Afghan President Hamid Karzai found out about the talks, he was furious, and they fell apart.

U.S.-Taliban talks began again in earnest as the Taliban prepared to open a representative office in Qatar in 2013. The plan at the time was that the discussions would be followed by talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government. The five prisoners were the first item on the agenda.

The process of swapping them for Bergdahl was meant to take two months, giving time for Congress to be notified. Halfway through the process, the Taliban would be required to give proof that he was alive. Then the five detainees would be released to Qatar, and Bergdahl too would be released.

However, the Taliban office was shut down within days of opening in June 2013, amid another uproar from the Afghan government. The Taliban then struggled to re-sell the talks to their foot soldiers, young fighters who felt they were winning and didn't need to give anything away.

In January of this year, it became clear that the U.S. and the Taliban had begun talking again. A new video of Bergdahl surfaced, and Bergdahl's statement referenced the death of Nelson Mandela, who had died in December.

That seemed to be the proof of life that the U.S. had been looking for.

Why did the Taliban go for the exchange now? One possibility is that the older generation of Taliban, which has been more interested in negotiations, wanted to show that there was an upside to talking to the United States by getting its prisoners back. In other words, it was a way of proving to a younger, more skeptical generation of Taliban fighters that talks with the U.S. and the Afghan government are worth pursuing.

The U.S. wants out of Afghanistan, but it doesn't want to leave behind complete chaos. In the past, it at least wanted to start a process of talks that could have some traction.

As the Taliban insurgency rages on, the question is whether the next Kabul government will risk talks with the militants, and whether the Taliban themselves may wish to negotiate for a share in power or will stay on the course of war.

In either case, the deal that came about this week after such a long gestation was about more than six men and their respective paths toward captivity and now freedom.