It's not how most 16-year-olds spend their time, crunching through the last snow cover of spring amidst an elaborate system of tubing, capturing one of nature's sweetest gifts.

Joshua Parker launched Parker Maple Farm from his rural family home in Canton, N.Y., aiming for success in a long and storied tradition, turning sap to maple syrup.

"My goal for this year is 1,500 gallons," said Parker. "I think it's realistic, but it all depends on what nature brings."

He's already closing in on the mark, having collected more than 1,100 gallons this season.

It's a big jump in production for the teenager who works to balance sports and school with his growing seasonal business.

"I guess what drives me is a love for it. I guess I have a passion for syrup," said Parker. "I got my inspiration from a local sugar house. I went on a visit a couple years ago and they showed me how to tap trees and they showed my how to hang the buckets and produce the syrup so from there I went home and borrowed 15 buckets and started tapping trees."

From there Parker's passion grew.

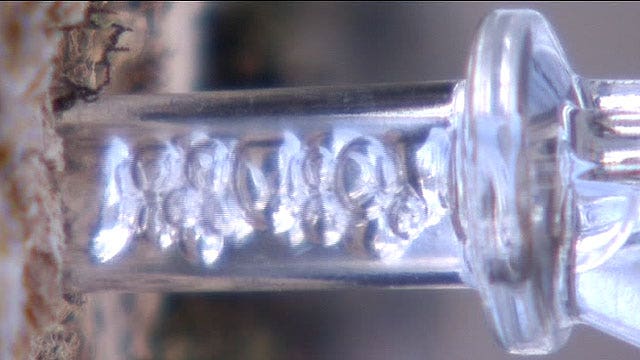

"With the 15 buckets, I then went to 30 buckets and then, from the 30 buckets to 60 buckets. Then, finally, I did 100 buckets for a couple of seasons," said Parker. "Now I finally went to about 3,500 taps this season."

He's one of the youngest entrepreneurs in a growing agricultural field.

Last year was a big one for the sticky stuff in the U.S. More than 3.2 million gallons were produced, up 70 percent over 2012 thanks to good weather and new technology. But experts say there is still much untapped potential in the industry.

"Production just about doubled in the last five to six years and we're poised for future expansion. We're still tapping less than one percent of all the Maple trees here in the U.S.," said Michael Farrell, director of Cornell University's Sugar Maple Research & Extension Field Station in Lake Placid, N.Y.

"We have the trees. The resource is there," argues Farrell. He believes billions of trees could be tapped. "The market is there and so we just need to continue to focus our efforts on expanding both the production and consumption of pure maple."

Back in 1860, U.S. sugar makers produced 6.6 million gallons of maple syrup, roughly double today's output. That was long before the modern development of corn-based and artificial sweeteners.

Farrell believes pure maple can compete.

"One of the benefits of growing the maple syrup industry in the U.S. is the amount of jobs it creates in rural communities, especially in a time of the year where there's maybe not as many jobs in late winter, early spring," said Farrell, who added that the industry could bring in roughly half a billion dollars in profits each season.

For now, Farrell said, pure maple makes up less than 10 percent of the total sales volume for pancake syrups. Most people across America are using an imitation syrup. He said the key to capturing more of the market is to convince people that pure maple is worth a little extra money.

"It's healthier and tastier and local- all the good things about pure maple that are not contained in the artificial competitors," said Farrell. "If you're going to have some sweet food pure maple is the best choice because it also contains a lot of minerals, in the syrup as well, there's antioxidants. There's lots of good things in the syrup besides just sugar and it is all natural."

He doesn't have to convince Parker.

"You can't beat pure maple syrup. There's nothing like it in the world," said Parker.