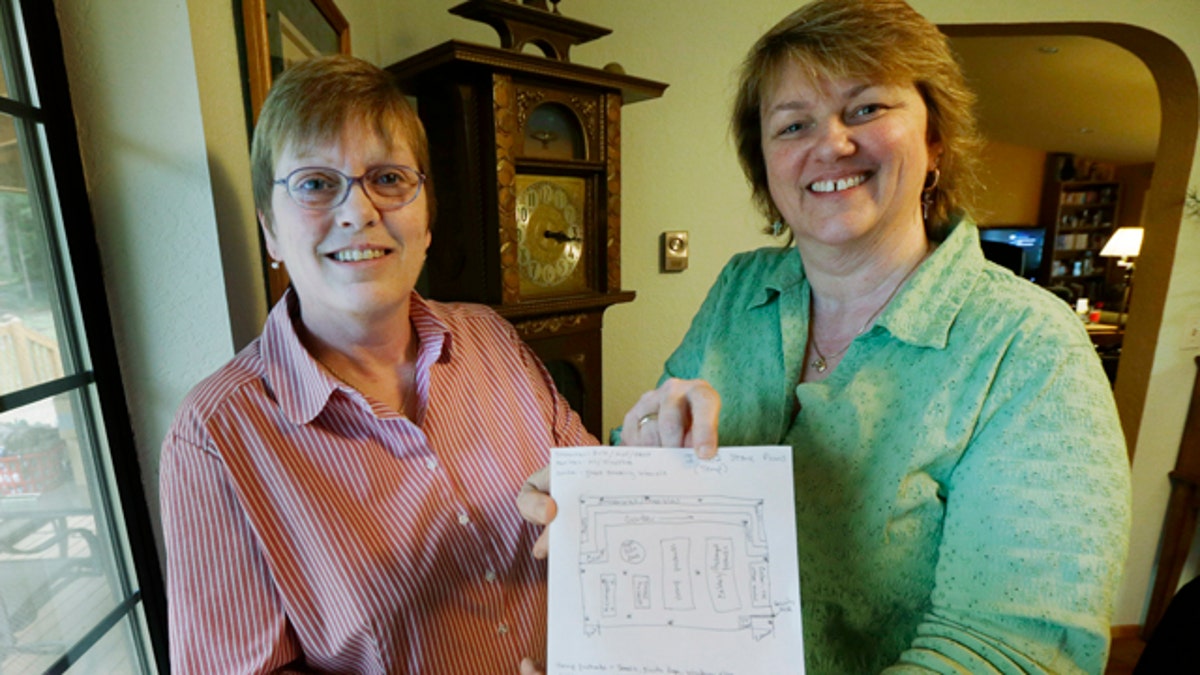

Mar. 5, 2013: Kim Ridgway, left, and her wife Kimberly Bliss, right, pose for a photo. (AP)

LACEY, Wash. – Kim Ridgway and her wife, Kimberly Bliss, can well envision the shop they plan to open -- where they'll put the accessories, the baked goods and the shelves stacked with their valuable product: jars of high-quality marijuana.

Like many so-called "potrepreneurs" throughout Washington and Colorado, they're scrambling to get ready for the new world of regulated, taxed marijuana sales to adults over 21 -- even though the states haven't even figured out how they are going to grant licenses.

Farmers and orchardists are studying how to grow marijuana. Some medical pot dispensaries are preparing to switch to recreational sales. Labs that test the plant's potency are trying to figure out how to meet standards the states might develop.

It's a lot of work for something that might never happen.

"We don't want to devote all our time and finances to building a business, only to have the feds rip it out from under us," Bliss said. "There's a huge financial risk, and a huge personal risk. We could end up in federal prison."

While marijuana remains illegal under federal law, both states legalized the possession of up to an ounce of marijuana last November and are setting up rules to govern state-licensed growers, processors and retailers.

Attorney General Eric Holder, who is due to appear Wednesday before the Senate Judiciary Committee, has said the Justice Department is in the final stages of deciding whether to sue to block the measures. State laws can be trumped if they "frustrate the purpose" of federal law.

A group of former Drug Enforcement Administration heads and the United Nations drug control group this week renewed calls for the administration to sue, and some legal scholars say it's hard to see how the schemes would survive a court challenge.

Nevertheless, tempted by dreams of changing people's perception of pot and making some decent money, Bliss and Ridgway are meeting with lawyers, recruiting investors, sketching store plans and scoping out locations -- all in the hopes of a grand opening on their first wedding anniversary.

After 28 years together, they got married in December on the first day the state's new gay marriage law allowed it. They say they like the idea of becoming pioneers in the cannabis industry, too.

Hilary Bricken, a Seattle lawyer advising those interested in the marijuana industry, said she's heard from people in many walks of life. Among them are a consulting firm that wants to help state-licensed growers make their operations environmentally friendly; a plant nursery that figures it already has the greenhouses; and a struggling chocolatier who sees financial salvation in "pot chocolate."

"It's super-exciting, and it's a testament to the power of industry," she said. "It's a solution for many people that are hurting economically right now, and for better or worse, they're brave.

"These are the people who are going to push the buck to change the national conversation," Bricken said.

Her law firm, Harris and Moure, has been advising clients to write business plans that cover everything from where they're getting their seed money and insurance to their security plans and protocols describing how they'll treat their employees or shareholders.

Kristi Kelly, owner of the Good Meds dispensary chain in the Denver area, is shopping for real estate and lining up investors for a potentially big expansion to the recreational market while she awaits the DOJ's decision.

She had some words of caution for green-eyed entrepreneurs looking to cash in on pot, though.

"Whatever you think it's going to cost, it's probably going to be 10 times that," Kelly said.

Since 2009, when Colorado's medical pot industry was booming, Kelly has seen many growers and sellers go bust. The industry has declined by at least a third since then, thanks in part to federal crackdowns and natural market adjustment.

Josh Chudnofsky, a 32-year-old who grows medical marijuana for patients in Snohomish, northeast of Seattle, wants to position himself to obtain a grower's license, but isn't sure how.

"Do I try to get an agricultural license and try to transfer it to a pot license? Do I get a small-business license?" he asked. "I've been calling around but nobody has any answers."

In the meantime, he's been making tentative plans to expand his 30-plant grow operation. He has lined up investors, checked on industrial and commercial spaces he could rent and talked about buying his own building. He has no criminal record, he noted, and he doesn't want one. If he doesn't get a license, he won't do it.

Ridgway, 50, and Bliss, 52, don't have much experience in the pot business, but Ridgway is an authorized patient and said she's been around dispensaries enough to know how they work. She uses marijuana to treat arthritis and severe anxiety; Bliss uses it occasionally to relax after work.

They have another thing going for them, they said: They previously worked at a wholesale meat company run by Ridgway's family, and know what it's like to have nitpicking inspections and regulations.

Ridgway hasn't worked since the company closed in 2010, and Bliss works as a part-time bookkeeper for a restaurant. Opening a marijuana store would give them earning potential they don't otherwise have as under- or unemployed women in their 50s, they said.

But their primary goal is to help change attitudes by helping to teach people how useful cannabis can be in its medical, recreational and industrial uses. Bliss said it will not only increase state tax revenue but benefit the entire community.

Smiling, she added: "I'm not going to be used to having that kind of money."