MIT develops system to 'shrink' objects

MIT researchers have developed a system to ‘shrink’ objects down to a nanoscale level using 3-D printing techniques.

Researchers at MIT have developed a system to “shrink” objects down to a nanoscale level.

While this may conjure up images of “Ant-Man” or “Honey, I Shrunk The Kids,” it’s actually a 3-D printing technique that could prove useful in fields such as medicine, robotics and optics.

"It's a way of putting nearly any kind of material into a 3-D pattern with nanoscale precision," said Edward Boyden, an associate professor of biological engineering and of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, in a statement.

DRONE FLEET COULD HELP FIND LOST HIKERS, MIT RESEARCHERS SAY

The researchers used a technique they describe as “implosion fabrication” to 3-D print objects at a nanoscale. Their work builds on an existing technique developed at Boyden’s lab for high-resolution imaging of brain tissue.

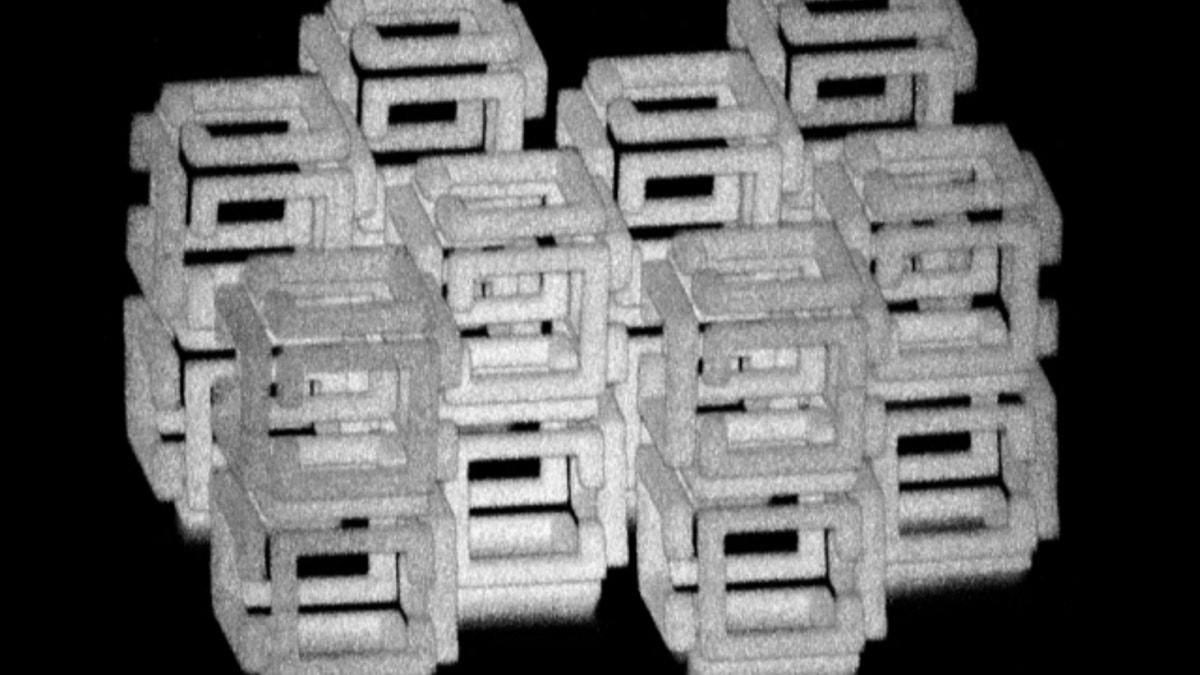

This image shows a complex structure prior to shrinking. (Daniel Oran)

“This technique, known as expansion microscopy, involves embedding tissue into a hydrogel and then expanding it, allowing for high-resolution imaging with a regular microscope,” explained MIT in the statement. “By reversing this process, the researchers found that they could create large-scale objects embedded in expanded hydrogels and then shrink them to the nanoscale.”

Similar to their research on expansion microscopy, the researchers used a highly absorbent material made of polyacrylate, which is commonly found in diapers, as the “scaffold” for their nanofabrication process. This was bathed in a solution that contained molecules of fluorescein, a compound widely used as a coloring agent. When activated by a laser light, the molecules attached to the “scaffold.”

SPRAWLING GALAXY CLUSTER DISCOVERED 'HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT'

Using two-photon-microscopy, the fluorescein molecules were attached to specific locations within the gel. "You attach the anchors where you want with light, and later you can attach whatever you want to the anchors," said Boyden. "It could be a quantum dot, it could be a piece of DNA, it could be a gold nanoparticle."

A paper on the research was published in the journal Science.

"It's a bit like film photography -- a latent image is formed by exposing a sensitive material in a gel to light," said Daniel Oran, an MIT graduate student, and one of the paper's lead authors, in a statement. "Then, you can develop that latent image into a real image by attaching another material, silver, afterwards. In this way implosion fabrication can create all sorts of structures, including gradients, unconnected structures, and multimaterial patterns,"

MIT RESEARCHERS GIVE THE WHITE CANE USED BY THE VISUALLY IMPAIRED A HIGH-TECH UPDATE

Scientists say they can then shrink objects 10-fold in each dimension, making an overall 1,000-fold reduction in volume.

“Once the desired molecules are attached in the right locations, the researchers shrink the entire structure by adding an acid,” explained MIT in its statement.

Using the technique, researchers say that they can create objects that are around 1 cubic millimeter, patterned with a resolution of 50 nanometers. “There is a tradeoff between size and resolution: If the researchers want to make larger objects, about 1 cubic centimeter, they can achieve a resolution of about 500 nanometers,” they explained. However, improvements to the process could eventually boost resolution.

ULTRALIGHT 'SUPER-MATERIAL' IS 10 TIMES STRONGER THAN STEEL

The system could be particularly useful for creating specialized lenses for the likes of cell phones, microscopes and endoscopes, according to the scientists involved in the project.

"There are all kinds of things you can do with this," explained Boyden, noting that the technology needed is already in many research labs. "With a laser you can already find in many biology labs, you can scan a pattern, then deposit metals, semiconductors, or DNA, and then shrink it down," he added.

The system is just the latest innovation to come out of MIT. In a separate MIT project, researchers have been developing sophisticated technology that uses drones to find lost hikers by searching under dense forest canopies.

In August, scientists at MIT announced the discovery of a galaxy cluster that they say is “hiding in plain sight.”

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers