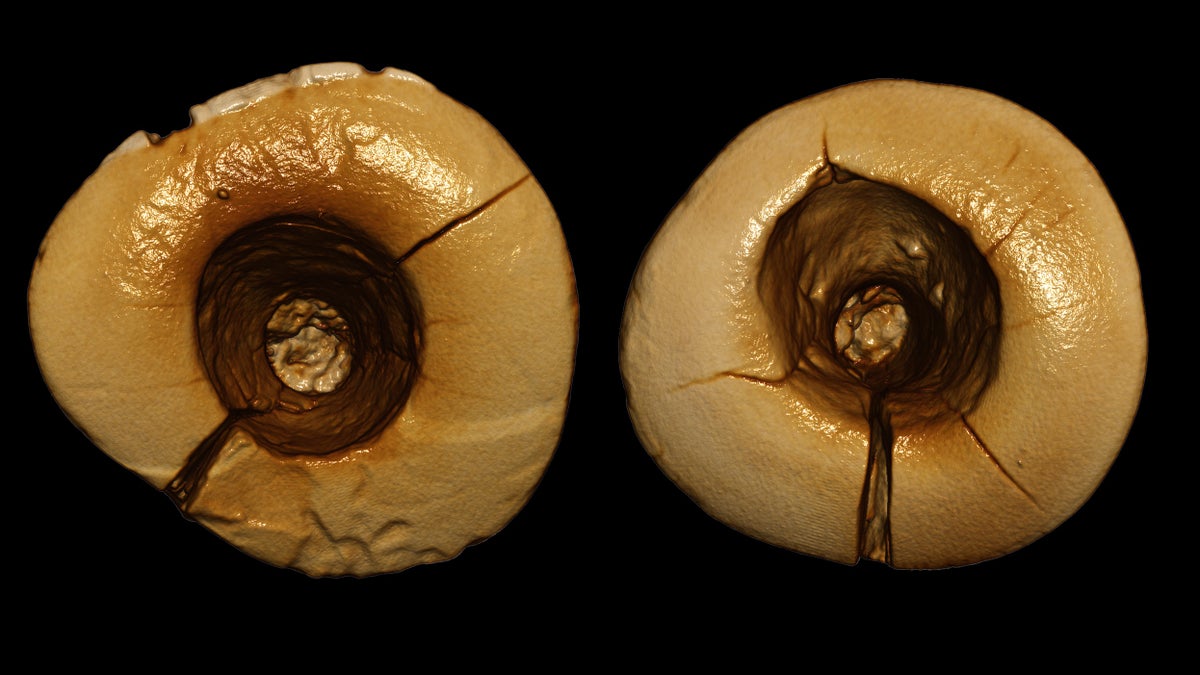

Archaeologists discovered a 13,000-year-old skeleton with two front teeth that have big holes in the surface that reach down to the tooth's pulp chamber. (Stefano Benazzi)

You might wince at the sight of your dentist holding an electric drill over your mouth. But, you can be thankful she's not using a stone tool instead.

That is what the most advanced dental care looked like thousands of years ago. By studying teeth at archaeological sites, scientists think that prehistoric humans came up with a variety of resourceful solutions to dental problems: people drilled out cavities, sealed crown fractures with beeswax, used toothpicks to relieve inflamed gums and extracted rotten teeth.

Now, researchers report that they've discovered what is perhaps the oldest known example of tooth-filling at an ice age site in Italy. [The 10 Biggest Mysteries of the First Humans]

Archaeologists unearthed the skeletal remains of a person who lived about 13,000 years ago at Riparo Fredian, near Lucca in northern Italy. The person's two front teeth (or upper central incisors) both had big holes in the surface that reach down to the tooth's pulp chamber.

More From LiveScience

Researchers recently analyzed horizontal striations inside the tooth holes, and concluded that these scratch marks were most likely produced by the scraping and twisting of a hand-held tool. This ice age person was probably in pain from necrotic or infected tooth pulp inside the teeth; seeking relief, they might have intentionally scooped out the decayed tissue, enlarging their cavities in the process, according to the study published online March 27 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

But the dental work didn't end there. Inside the tooth cavities, there were traces of bitumen, a tar-like substance that might have been used as an antiseptic or a filling to protect the tooth from getting infected, the researchers said.

Alejandra Ortiz, a postdoctoral researcher at Arizona State University's Institute of Human Origins who wasn't involved in the study, said she finds the authors' argument for dentistry highly convincing.

"Until now, the earliest evidence of dental filling came from a 6,500-year-old human tooth from Slovenia ," Ortiz told Live Science. "This new finding adds another piece of information for a possible emergence of oral health practices before modern carbohydrate-rich diets led to an enormous increase in dental caries ," also known as cavities.

Study co-author Stefano Benazzi, an archaeologist at the University of Bologna, said that the only earlier example of such paleo-dentistry comes from a nearby site. A few years ago, Benazzi and his colleagues also studied this specimen , a 14,000-year-old tooth from Villabruna in northern Italy with a scraped-out, but not filled, cavity.

Benazzi told Live Science that these examples from Villabruna and Riparo Fredian attest that something was changing during this time. Scientists have increasing evidence suggesting that during the late upper Paleolithic, some dental diseases, like cavities, were on the rise in some populations , which could be related to changes in diet, food processing or culture, Benazzi said.

"Actually we do not know, but maybe the increase of dental problems drove some populations to develop dental treatments," Benazzi added.

Original article on Live Science .