Treating America's Pain: Unintended Victims of the Opioid Crackdown, Part 1 – The Suicides

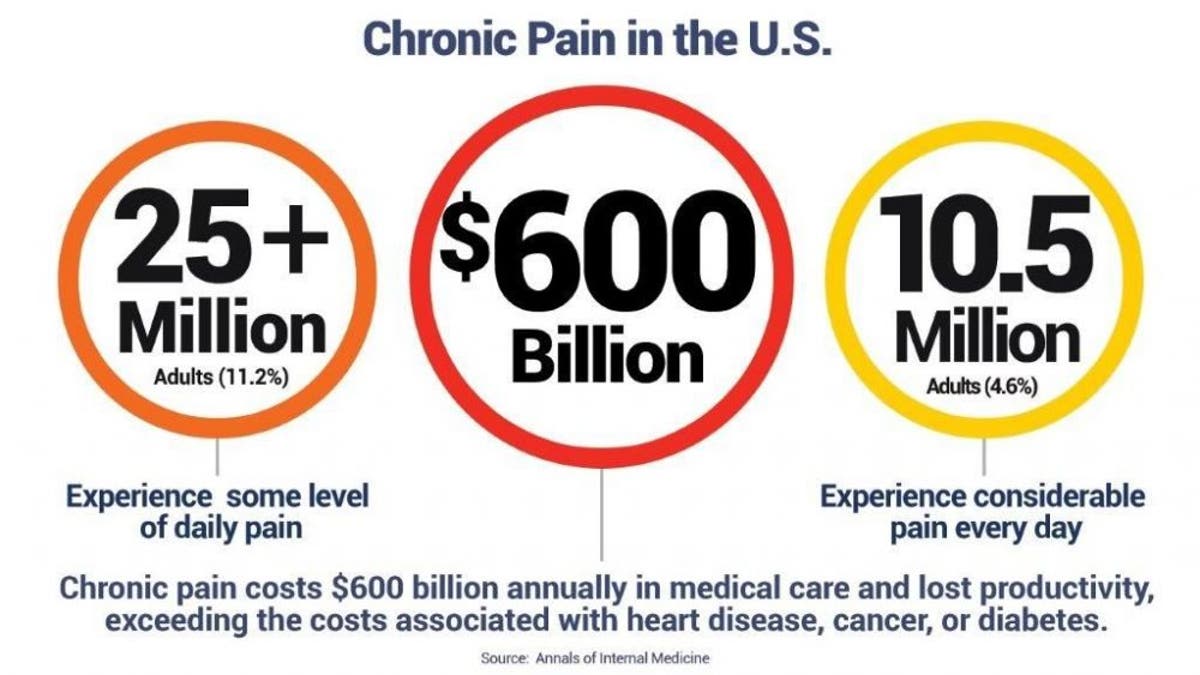

The national opioid crisis propelled a crackdown on prescription painkillers, causing hundreds of doctors to abruptly reduce or completely cut off their patients’ prescriptions, leaving many among the estimated 20 million Americans who suffer from daily debilitating chronic pain to consider suicide. This is the story of the overlooked victims of America's opioid epidemic.

This is the first of a three-part series on the nation's struggle to address a crippling opioid crisis, and the unintended victims left in its wake.

It happened slowly. The pain caused by a 1980 back fracture, the result of a tractor-trailer crash, crippled more and more of Jay Lawrence’s body and spirit.

By 2006, the Tennessee native and Navy veteran’s arms and legs were going numb. The excruciating pain reduced him to tears. Multiple surgeries, chiropractic adjustments, and physical therapy didn’t work.

He finally found solace in prescription painkillers – 120 milligrams a day of morphine. A high dose, but it dulled the pain enough for him to take walks with his wife, shop for groceries, even take in a few movies.

But last February, the pain clinic doctor delivered jarring news: He was cutting Lawrence’s daily dosage, first to 90 milligrams then, in short stages, down to 30 milligrams. The doctor said the reduced dosage was in response to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prescribing guidelines released in 2016 as part of a national anti-opioid push, according to Lawrence’s wife, Meredith.

“The doctor said: ‘You know these guidelines are going to become a law eventually. So we've decided as a group that we're going to take all of our patients down,’” she told Fox News in an interview.

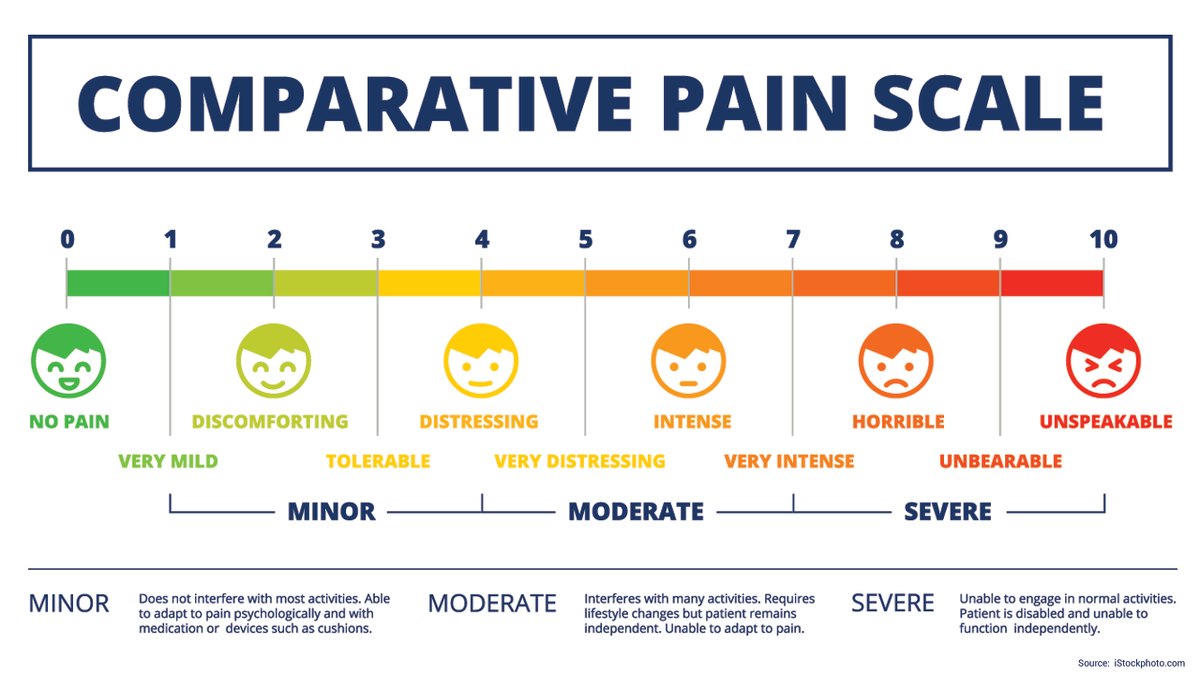

Lawrence’s pain returned with a vengeance. He could barely move or sleep. He soiled his pants, unable to make the bathroom in time, Meredith said.

“It feels like every nerve in my body is on fire,” he told his wife.

Meredith said she and her husband went to their primary care physician and asked for a referral to another pain clinic. They were told it would take a minimum of six weeks.

That was too much for Lawrence. In March, on the day of his next medical appointment, when his painkiller dosage was to be reduced again, he instead went to a nearby park with his wife. And on the very spot where they renewed their wedding vows just two years earlier, they held hands.

He raised a gun to his chest and killed himself.

Jay and Meredith Lawrence (Savannah DeAnn Photography)

Lawrence, who was 58, became one of an undetermined number among the nation’s 20 million chronic pain sufferers who chose suicide after being cut back or denied prescriptions for opioids. The suicides have motivated many of those who continue to suffer from pain - and family members and advocates of those who took their lives – to call for a re-evaluation of the rush to reduce opioid dosages for those who most need them.

“We have a terrible problem. We have people committing suicide for no other reason than being forced to stop opioids, pain medication, for chronic pain,” said Thomas Kline, a North Carolina family doctor and former Harvard Medical School program administrator.

“It’s mass hysteria, a witch hunt. It’s one of the worst health care crises in our history,” said Kline, who has 26,000 Twitter followers, and a website where he publishes the names of those who he said committed suicide after having their opioids cut back or eliminated. “There are five to seven million people being tortured on purpose.”

The CDC doesn’t have numbers of those who commit suicide after having their pain medications cut. But most of the doctors who spoke to Fox News said they knew of between one and six patients who took their life after losing access to opioid treatment, and being turned away from other doctors who now see prescription painkillers as a hassle.

Several prominent doctors and pain patient advocacy organizations said they have heard from hundreds who say they have been left in debilitating pain and are considering suicide. The issue earlier this year came to the attention of Human Rights Watch, which launched an investigation.

"Clearly, there are patients now who feel like life is not worth living if they return to living in pain," said Diederik Lohman, director of Health and Human Rights for Human Rights Watch. "Many of the patients we spoke to are very law-abiding, and would turn to suicide before going to the street to get illicit drugs. The government has a duty to respond to the overdose crisis but to do so in a way that is harming people who have a legitimate medical issue is a human rights issue."

We have a terrible problem, we have people committing suicide for no other reason than being forced to stop opioids, pain medication, for chronic pain. It’s mass hysteria, a witch hunt. It’s one of the worst health care crises in our history. There are 5 to 7 million people being tortured on purpose.

Many pain patients say they understand the urgent need of political leaders and government agencies to fight the drug overdose epidemic. But targeting the millions who legitimately suffer from chronic pain is grasping for a solution that doesn’t address the preponderance of illegal drugs, they argue - or the rate of overdoses caused by them.

The CDC released a report Nov. 30 showing that despite a drop in painkiller prescriptions over the years, the drug overdose rate continues to soar, with the growth driven by the illicit opioid fentanyl and its cousins. It is a trend that has held for several years.

“People with pain shouldn’t have to suffer because people without pain are abusing opioids,” said Cynthia Toussaint, a former ballerina from California, who has Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), which left her bedridden for 10 years, and unable to speak for five. “Pain patients don’t want to take opioids any more than cancer patients want to use chemotherapy. However, many people with pain need opioids to function physically and pursue the joyful aspects of life.”

At a recent American Medical Association (AMA) meeting, the group’s president, Dr. Barbara McAneny, spoke of how an advanced prostate cancer patient of hers attempted suicide after he was denied opioids by an insurer. “The pendulum swung too far when pain was designated a vital sign, and now we are in danger of it swinging back so far that patients are being harmed,” she said, according to published reports.

ISSUES WITH CDC GUIDELINES

Federal officials have said the CDC guidelines weren’t intended to disrupt the proper prescribing and use of opioids. “We’re not telling any doctor that they can’t make a legitimate prescription,” then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions told Fox News, in an interview before he left office. “Maybe some doctors are getting too cautious. We don’t know.”

Sessions acknowledged “opioid prescribing can be essential for people,” and said, “it’s very clear that people with serious pain problems are in need of real significant pain relief and sometimes [opioids] are the only thing that will provide relief, and it is absolutely legitimate to prescribe it.”

We have heard about the suicides...It's tragic that anyone takes their life for any reason, including that they had their opioids unilaterally stopped.

CDC officials added they are also aware chronic pain sufferers have committed suicide in their struggle to get by with fewer or no opioids.

“We have heard about suicides,” said Dr. Debbie Dowell, a senior CDC medical advisor, and lead author of the guidelines on opioid prescribing. “We’ve heard the reports. It’s tragic that anyone takes their life for any reason, including that they had their opioids unilaterally stopped.”

Dowell said the scope of suicides caused by under-treatment of chronic pain “isn’t something that’s easy to measure. We’ve looked at how we might measure this. Sometimes patients or their families don’t report it.”

The CDC guidelines focused on primary care physicians and recommended extreme caution in prescribing opioids. It also suggested a maximum daily dosage of 90 morphine milligram equivalents for first-time painkiller patients.

But the guidelines also warned against forcibly tapering or abruptly cutting off severe pain sufferers who have responsibly have taken opioids, noting that a drastic change could lead to withdrawal, and serious illness.

Untreated pain, many health experts say, can also lead to hypertension, more serious pain conditions, and other problems. Health practitioners say this is a plight that could affect anyone -- all it takes is a slip, a fall, or a botched surgery that could bring on intense and perhaps long-term pain.

Dowell said patients should be prescribed on a case-by-case basis.

“We believe everyone deserves effective pain management,” she said. “The CDC guidelines are not a regulation or a law – it’s guidance for providers.”

“It never made a recommendation to take people off medication involuntarily, or to taper down involuntary," she said. "It was meant to provide updated guidance about the benefits and risks of opioids for chronic pain so that the provider and the patient – together – could make decisions.”

GUIDELINES BECOME ENFORCEMENT TOOLS

The CDC disclaimer was apparently lost among the headlines about the staggering number of deaths due to opioids. Political leaders and government officials often failed to note the bulk -- at least 60 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services -- of the overdose epidemic was caused by illicit drugs, not prescription painkillers.

And when officials did address the portion of deaths due to prescriptions, advocates of safe opioid use argue, they often lumped together pain patients and people with addiction who illegally obtained someone else’s prescribed opioids. That made for a perfect storm, which formed the basis for a slew of hardline state and federal policies, including a Trump administration vow to slash prescriptions by 30 percent over the next three years.

Either in response to the CDC guidelines or as proactive measure to deal with the opioid crisis on their own, at least 33 states have enacted some type of legislation related to prescription limits, according to the National Conference of State Legislators. Health care providers and pain patients who have Medicare prescription plans are bracing for January, when the federal insurance program will give its insurers and pharmacists the authority to reject prescriptions that deviate from CDC recommended dosage.

“The CDC guidelines were geared to primary care doctors, but they have been hijacked and weaponized as an excuse for draconian legislation,” said Michael Schatman, a clinical psychologist and director of research and development at Boston Pain Care, a multi-disciplinary pain clinic, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Pain Research. “Illicit opioids, not prescription opioids, are driving overdose deaths.”

The CDC guidelines...have been hijacked and weaponized as an excuse for draconian legislation.

The disproportionate focus on prescription painkillers by officials responding to the overdose epidemic, pain specialists and public health researchers say, is in great part why the drug-related death rate continues to climb while legal opioids becomes less available to pain patients.

“We’re targeting the most vulnerable and sickest people who have been on opioids a long time,” said Dr. Stefan Kertesz, an addiction specialist and professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. “Insurers are issuing rules that say we won’t cover long-term opioids for anyone over 90 milligrams. Well, five percent of people who receive opioids account for 60 percent of the milligrams prescribed. With so many milligrams going to a tiny group of very sick people, if you can knock a few people off these opioids you can show a big numeric reduction.”

“What we’re really doing is dragging down the dose on the most disabled people,” said Kertesz, who sits on several state opioid safety committees. “Prescription control seems an easy answer to the epidemic, but that’s not stopping addiction.”

CRIES FOR HELP, AND GIVING UP

On social media, comments sections on news sites, and in emails to Fox News, numerous pain sufferers say they have made suicide plans because their health care provider has forcibly reduced their dose to a deficient level, or cut them off entirely. They speak of being treated like drug abusers, submitting to frequent urine tests and pill counts.

Jay and Meredith Lawrence (Courtesy of Meredith Lawrence)

"I have been on pain management since 2006," said a man from Tampa in a Facebook message. "Have a crippling disease that there is no cure for, and can no longer get the medications I need. A few months ago I was researching death with dignity and other options for assisted suicide if I wasn’t able to get the help needed down the road."

Some posted comments about a loved one who died by suicide after losing access to a long-term treatment for pain, and finding it intolerable to continue suffering. Others said their spouse’s suffering, together with the frustration and anguish of being turned away or undertreated by doctors, was the reason they came around to accepting their loved one’s suicide plan.

In her new home in Georgia, its walls covered with pictures of her late husband, Meredith Lawrence recalled the helplessness she felt watching him suffer, as the pain worsened, and the drugs were tapered down.

“He said ‘I have three choices,’” Meredith recalled. “He said ‘I could do illegal drugs, I could suffer the rest of my life in pain, or I can end my life. I’m not going to do the first two.’”

Lawrence’s doctor did not respond to email and phone requests to comment for this story.

Meanwhile, hashtags on Twitter like #SuicideDue2Pain, #DontPunishPain, #PatientsNotAddicts have become common.

People with pain shouldn't have to suffer because people without pain are abusing opioids.

“I think about suicide every day,” said Dawn Anderson, a former trauma nurse from Indiana, whose doctor cut her opioid dosage after his office was raided by the DEA.

“I recently wrote a suicide note to my family,” said Anderson, a diabetic whose legs were both amputated below the knee. “They have seen all I have gone through. I want to live. But not like this.”

Anderson, 53, now finds it too painful to stand on prosthetics because of what she says is undertreated pain, and is confined to a wheelchair.

“The pain feels like an electrical shock that happens every 30 seconds in some parts of my body,” she said, “and in the back it’s a stabbing pain, like a hot poker that is stuck and never coming out. The pain I endure on a daily basis is taking my will to live.”

Anderson’s doctor did not respond to requests for comment.

Anne Fuqua, a former nurse in Alabama who herself suffers from chronic pain, has logged records of 167 suicides since 2014 that she maintained were directly a result of patients who had their opioids reduced or cut and suffered uncontrolled pain.

Fuqua said she is in the midst of verifying more suicides that have been reported to her.

Caylee Cresta, a 26-year-old Massachusetts woman, has a rare disease, Stiff Person’s Syndrome, that causes muscle spasms and rapid convulsions that fracture her bones and often leave her stuck in an unnatural position for days. She has had the condition since she was 19.

"You're in fear that your doctor will say that your next prescription is your last," Cresta said, adding that when she has "a bad day" it means “I stop being a mother, a wife, a daughter.”

Ending the pain by ending it all has seemed, at times, like the way out.

Dr. Stefan Kertesz

CALLING FOR TOUGHER ANTI-OPIOID POLICIES

Not everyone agrees the problem is the cutting back of legal opioid prescriptions.

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, who directs opioid research at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, believes government policies on opioids need to be even tougher.

Kolodny, who also is executive director of the Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and one of the nation’s most vociferous critics of opioids, balks at the alarm sounding over the decreasing supply of prescription painkillers.

“The effects of hydrocodone and oxycodone produced in the brain are indistinguishable from the effects produced by heroin,” Kolodny said. “So my point is that when we talk about opioid pain medication, we’re essentially talking about heroin pills.”

Kolodny said opioids have an important role - in limited circumstances - such as ending suffering “at the end of life for some patients,” and “for a couple of days after major surgery.”

When we talk about opioid pain medication, we're essentially talking about heroin pills.

Many pain experts and patients blame Kolodny for pushing the federal agencies, particularly the CDC, to treat opioids as if it were heroin, and pain patients as people who are one opioid away from being addicts.

Kolodny said that isn't true.

“No role - none - zilch,” he said. “PROP was one of many organizations that was asked by CDC to offer them feedback on the guideline. Our letter is publicly available. CDC did not make the changes we requested.”

To Kolodny, “It’s a manufactured controversy … They’ll say with my opioid, I can at least get up from bed. For a heroin user it’s the same thing for them. They say they feel horrible, can’t do anything or function until they take their first dose of heroin in the morning.”

Former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions (Reuters)

FEDS SAY THEY’RE AT WAR

Sessions appeared to view the issue as a war that needs to be fought, full-speed ahead.

“This is the greatest health hazard we’ve had,” he said of fatal overdoses.“Let me just say this to the suicide problem and other problems: They’re arising out of addiction to those drugs,” he said. “People don’t know how powerful these addictions are. So people get into a situation where they can’t keep taking the drugs, and some of them might conclude they can’t live without them."

"We need to break that cycle," Sessions said. "We’re making progress at it, but we still prescribe far more pain pills than in any country in the world … we as a nation need to face up to that fact.”

Federal and state officials at the agencies at the forefront of the fight against opioids - including the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) – were hard-pressed to provide details to Fox News about just how many overdose deaths involved those legitimately prescribed opioids. A report by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, widely cited by many pain experts, said that among 477 people whose deaths were opioid‐related in 2018, 90 percent, or 423 of them, tested positive for fentanyl – a telltale sign of illegal opioid use.

Pain management experts said they share the concern and alarm over the terribly high percentage of drug overdoses.

“I share the nation’s concern that more than 100 people a day die of an overdose. But my patient nearly died of an under-dose,” said McAneny, the AMA president.

“My patient suffered, in part, because of the crackdown on opioids… When I visited my patient in the hospital as he was recovering from his suicide attempt, I apologized for not knowing his medication was denied," McAneny said. "I felt I had failed him.”

If you’re thinking about suicide, are worried about a friend or loved one, or would like emotional support, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline network is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, across the United States. The Lifeline is available for everyone, is free, and confidential -- 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

The deaf and hard of hearing can contact the Lifeline via TTY at 1-800-799-4889. Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio --1-888-628-9454

PART II: DOCTORS CAUGHT BETWEEN STRUGGLING OPIOID PATIENTS AND CRACKDOWN ON PRESCRIPTIONS

SIDEBAR: TOUGH NEW OPIOID POLICIES LEAVE SOME CANCER AND POST-SURGERY PATIENTS WITHOUT PAINKILLERS

PART III HEALTH EXPERTS OFFER SOLUTIONS FOR UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF OPIOID CRACKDOWN