Ancient Roman dirty jokes discovered in latrine mosaics

Archaeologists have found second-century mosaics, inside a Roman latrine in the coastal city of Antiochia ad Cragum, showing scenes that clearly play on myths of Narcissus and Ganymede.

As men relieved themselves at the public toilets in the coastal city of Antiochia ad Cragum some 1,800 years ago, they probably would have been amused by dirty scenes crafted into floor mosaics, archaeologists have found.

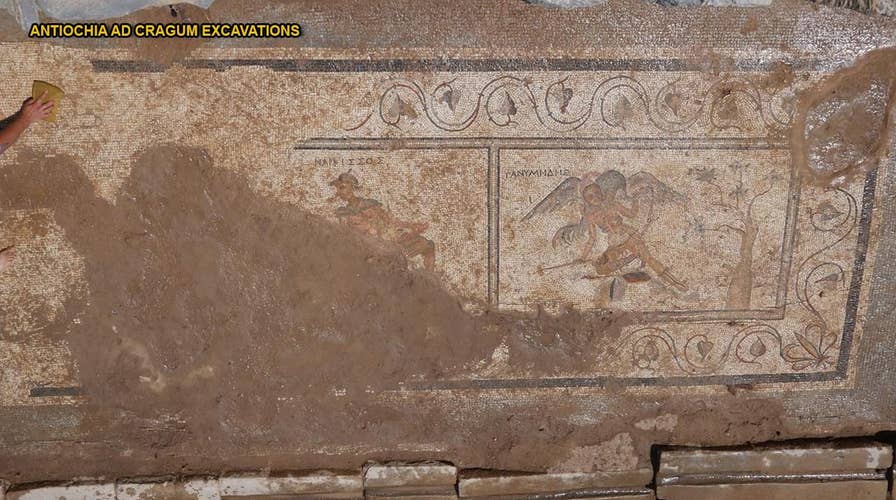

The second-century mosaics, found inside a Roman latrine in Turkey, show scenes that clearly play on myth: Narcissus fascinated with his own phallus and Ganymede getting his genitals sponged clean by a bird.

"We were stunned at what we were looking at," said Michael Hoff, an archaeologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "You have to understand the myths to make it really come alive, but bathroom humor is kind of universal as it turns out." [Image Gallery: Pompeii's Toilets]

Narcissus and Ganymede

More From LiveScience

The two mosaic scenes twist common tropes in Greek and Roman art. Narcissus is typically shown falling in love with his own reflection in water. In the mosaic at Antiochia ad Cragum, which was likely created in the second century, only half of the scene is preserved —but, Hoff told Live Science, "it's the good half."

Narcissus is shown with an uncharacteristically long nose, which would have been considered ugly by the beauty standards of the time. He looks down, presumably admiring the reflection of his conspicuous penis instead of his face.

In myth, Zeus disguised himself as an eagle to kidnap the Trojan adolescent Ganymede and make him a cupbearer to the gods. (The myth offered a model for relationships between men and adolescent boys in ancient Greece.) In art depicting that abduction, Ganymede is often shown holding a stick and rolling hoop as a toy.

In the image in the latrine, Ganymede instead holds tongs with a sponge, a reference to the sponges that would have been used for wiping the toilet. And Zeus is not an eagle but a heron, with a long beak grasping a sponge and dabbing Ganymede's penis. [Through the Years: A Gallery of the World's Toilets]

"Instantly, anybody who would have seen that image would have seen the [visual] pun," said Hoff. "Is it indicative of cleaning the genitals prior to a sex act or after a sex act? That's a question I cannot answer, and it might have been ambiguous then."

A latrine for large crowds

The rare bathroom mosaics were revealed during the last couple days of this past summer's excavation season at Antiochia ad Cragum, on the southern coast of Turkey. "There is a well-known axiom in archaeology that you find your best stuff on the last day," said Hoff, who is co-director of the project. The team had to cover up the toilet art for its protection, but Hoff said the researchers plan to expose the mosaics again next summer for further study and conservation work.

The latrine would have had clean water channels as well as seats made of marble or wood, which are now lost. Hoff said he suspects the public bathroom would have been used primarily by men. It shared a wall with the grand bath and was next to the bouleuterion, or council house, and "should have served the large crowds with its location," said Birol Can, a mosaic expert at Uşak University in Turkey, who worked on the excavation.

"Of course, all of the ancient cities had latrines, but not all of them have been exposed or

survived to the present day," Can said in a statement. "The number of mosaic-paved latrines is very low. Antiochia ad Cragum latrine is one of the rare examples."

The artworks are also the only examples of figurative mosaics found at Antiochia ad Cragum. Hoff and his colleagues previously uncovered a huge mosaic next to a pool in the bath complex, but this artwork featured only geometric patterns.

A literal buried treasure

Established around the era of Emperor Nero in the first century, Antiochia ad Cragum may have had a population of more than 6,000 people at its peak. The city was abandoned by the 11th century. During the following centuries, the secluded Roman ruins might have been a good place to hide loot —or a body —at least according to other evidence the archaeologists uncovered this year.

In the vaulted chamber of another bath building right outside the city gates, the archaeologists found a stash of more than 3,000 mostly silver, early 17th-century coins from all over Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

"It's pretty clear that these coins were purposely buried in order to keep them hidden, with the plan of retrieving them at a later date," Hoff said. He added that he can't be sure yet whether the coins were a Mediterranean pirate's stash or "some ill-gotten treasure" from the inner reaches of Anatolia. "Maybe once we get all these coins clean and understood, we'll learn a little more."

Several feet below where the coins were buried, the archaeologists also discovered a skeleton.

"Our physical anthropologist believes it may have been a murder [victim] or someone who was violently killed and their body was dumped in this location," Hoff said.

Original article on Live Science.