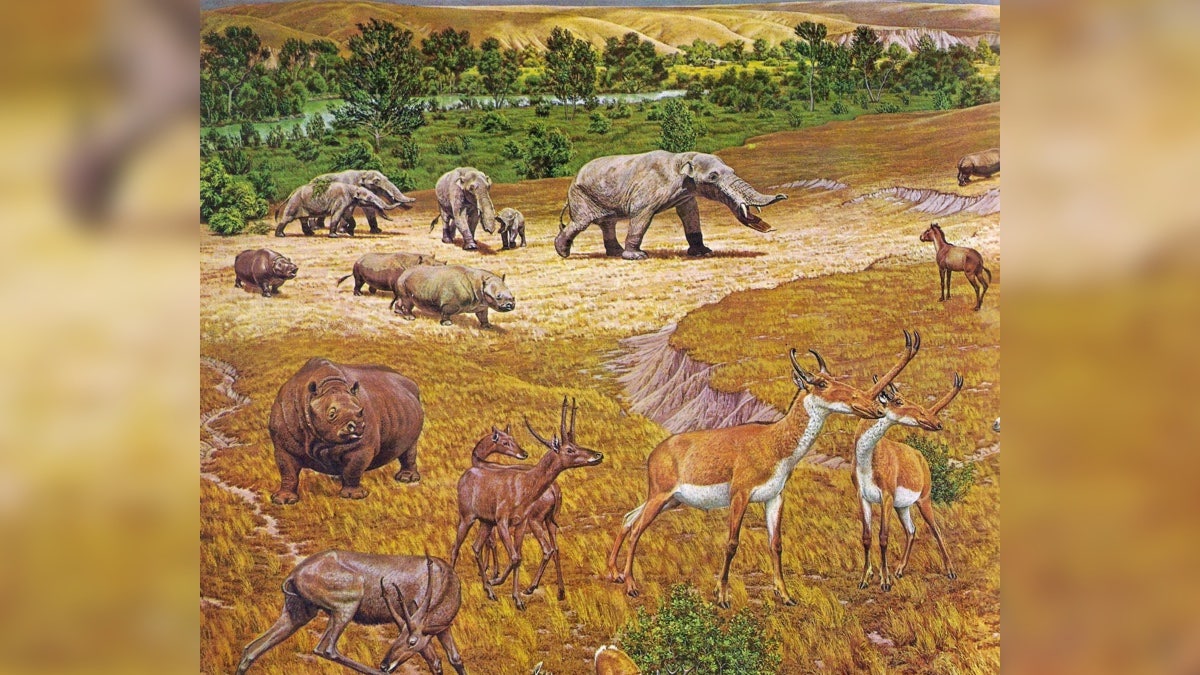

An illustration showing the ancient animals — such as elephant-like gomphotheres, rhinos, horses and antelopes with slingshot-shaped horns — that lived near what is now Beeville, Texas, about 12 million years ago. (Jay Matternes/The Smithsonian Institution)

About 12 million years ago, antelopes with slingshot-like horns and beasts that weren't quite elephants but that had long trunks and tusks tramped across the "Texas Serengeti" searching for food and caring for their babies.

Little was known about this ancient menagerie until, during the Great Depression, the government created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and tasked some of the organization's employees with finding and preserving thousands of fossils from the Miocene, an epoch that lasted from about 23 million to 5 million years ago.

Now, after more than 80 years in storage at The University of Texas at Austin, these fossils are finally being studied. The fossils have even revealed a previously unknown genus of gomphothere, an extinct elephant relative with a shovel-like lower jaw, and the oldest fossils on record of both the American alligator and an extinct dog relative. [Photos: These Animals Used to Be Giant]

These fossils, collected from 1939 to 1941, are an absolute treasure trove, scientists said. In the nearly 4,000 specimens, found at dig sites near Beeville, a city about 90 miles (145 kilometers) southeast of San Antonio, there are 50 species of fossil vertebrates (animals with backbones), including five species of fish, seven reptiles, two birds and 36 mammals.

More From LiveScience

The selection of animals is mind-boggling, revealing that rhinos, camels, rodents, 12 types of horses and five species of carnivores trekked across what is now the Texas Gulf Coast some 11 million to 12 million years ago.

"It's the most representative collection of life from this time period of Earth history along the Texas coastal plain," study researcher Steven May, a research associate at The University of Texas at Austin's Jackson School of Geosciences, said in a statement.

Though others have examined specific fossils in this collection, May's deep dive into the entire assortment is helping to fill gaps in the state's record of ancient wildlife, Matthew Brown, the director of the museum's vertebrate paleontology collections, said in the statement.

May also returned to the original dig sites to see what smaller fossils, such as rodent teeth, he could excavate, since the collected finds consisted mostly of big, "obvious" fossils, he said. There are so many fossils from the WPA era that the project will likely continue for years. In addition, researchers plan to do isotope analyses of the fossils. (Isotopes are different versions of an element that have different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus.) This will help scientists evaluate the diets and paleoenvironments of some of the ancient animals, May wrote in the study, which was published online yesterday (April 11) in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

- Photos: Fearsome Ancient Otter Was As Large As a Wolf

- 10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America

- Photos: Perfectly Preserved Baby Horse Unearthed in Siberian Permafrost

Originally published on Live Science.