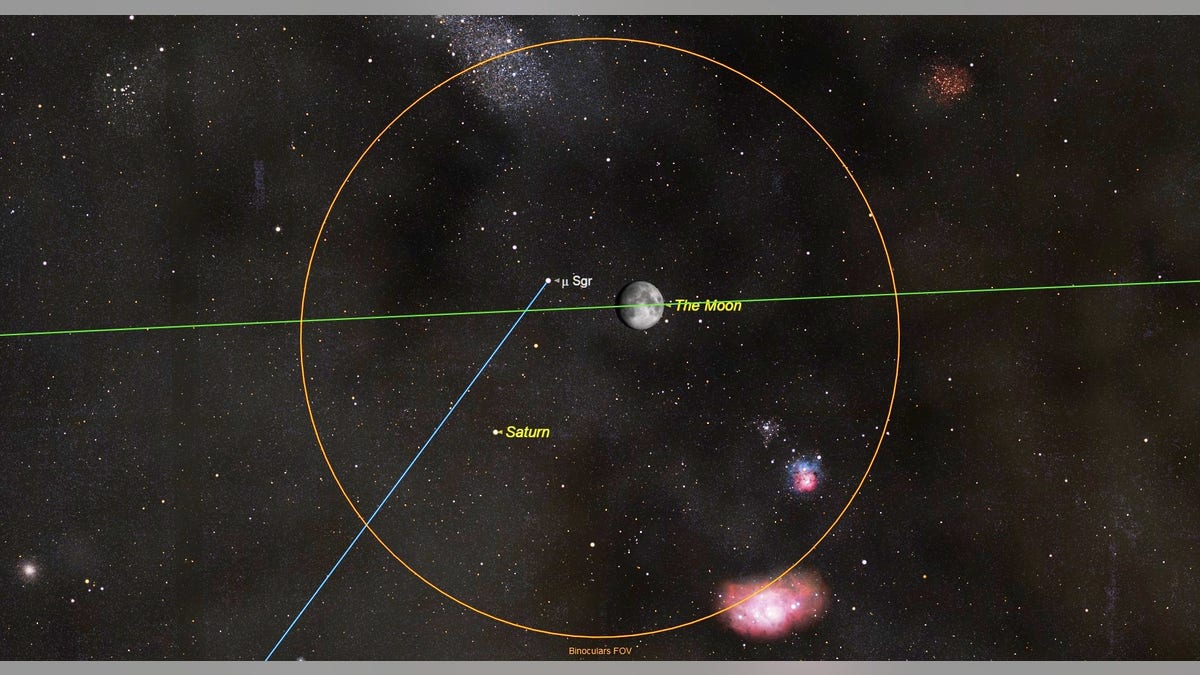

In the southeastern sky after dusk on the evening of Tuesday, July 24, the full moon will sit 2 degrees to the upper right of bright, yellowish Saturn. The two objects will cross the sky together during the night and will easily fit within the field of binoculars (orange circle) or a telescope at very low magnification. Meanwhile, the moon's separation from the bright planet will noticeably decrease as the moon slides eastwards in its orbit (green line).

Step outside around 9:30 p.m. local daylight time on Tuesday (July 24), and in a single glance, you'll be able to drink in a "parade" of bright planets.

Clearing the western horizon at an altitude of 10 degrees (the width of your fist held at arm's length) will be Venus, appearing absolutely dazzling at a magnitude of -4.2.

Nearly three times higher than Venus in the southwest sky (albeit one-sixth as bright) will be another brilliant planet: Jupiter. Although not as bright as Venus, Jupiter is a dazzling object in its own right, shining nearly eight times brighter than Arcturus, the brightest star of the summer sky. [Visible Planets, July 2018: When and How to See Bright Planets]

Then, sitting about 5 degrees above the southeast horizon will be Mars, now resplendently bright and nearing its closest approach to Earth in almost 15 years. The latest reports from experts measuring the brightness of Mars indicate that, due to a planetwide dust storm, the Red Planet is showing an "extra" brightness because the dust cloud reflects more light than the surface does. Therefore, their measurements show that Mars is about 0.20-magnitude brighter that it is listed, or an eye-popping -3.0 magnitude. And instead of sporting its distinctive reddish-orange color, Mars now appears to be more of an orange-yellow hue.

More From Space.com

And then there is a fourth planet — Saturn. But unlike the other planets mentioned, there really isn't anything visually distinctive about it in the night sky.

It appears as a bright "star" shining with a steady, sedate, yellow-white glow, but compared with Venus, Jupiter and Mars, it really isn't as eye-catching. Many who are just starting out in astronomy likely have passed over it without knowing exactly what it is. If you are among this group, be sure to put a big circle around Tuesday on your calendar.

About 1 hour after sunset that evening, look toward the south-southeast sky. About one-quarter up from the horizon to the point overhead will be a waxing gibbous moon, illuminated 93 percent by the sun. (The moon will officially turn full on Friday, July 27.)

And hovering to the moon's lower left will be a bright, yellowish-white "star" shining with a steady glow: the planet Saturn. The moon will appear to edge closer to Saturn as the night goes on, and the two objects will appear closest together — just 1.3 degrees apart — low in the southwest between midnight and dawn.

Now that you've properly identified these objects, if you have a telescope, you can try this out on Saturn. Coincidentally, for a bright planet that appears the least "showy" compared to others, Saturn, with its magnificent ring system, just might be the most spectacular of all when viewed through a telescope.

Any telescope magnifying more than 30 power will readily show those rings; you might even catch a glimpse of them through image-stabilized high-power binoculars. The rings consist of billions of particles ranging in size from grains of sand to flying mountains, which are made of — or covered by — water ice. This would account for their very high reflectivity. The differences in brightness define distinct sets of rings.

Right now, the north side of the rings is tilted 26.3 degrees toward Earth, almost as wide open as they can get.

And if clouds hide your view of Saturn and the moon, you'll have another chance to see them pair off again (though they won't be as close as on Tuesday) on the evening of Aug. 20.

Original article on Space.com.