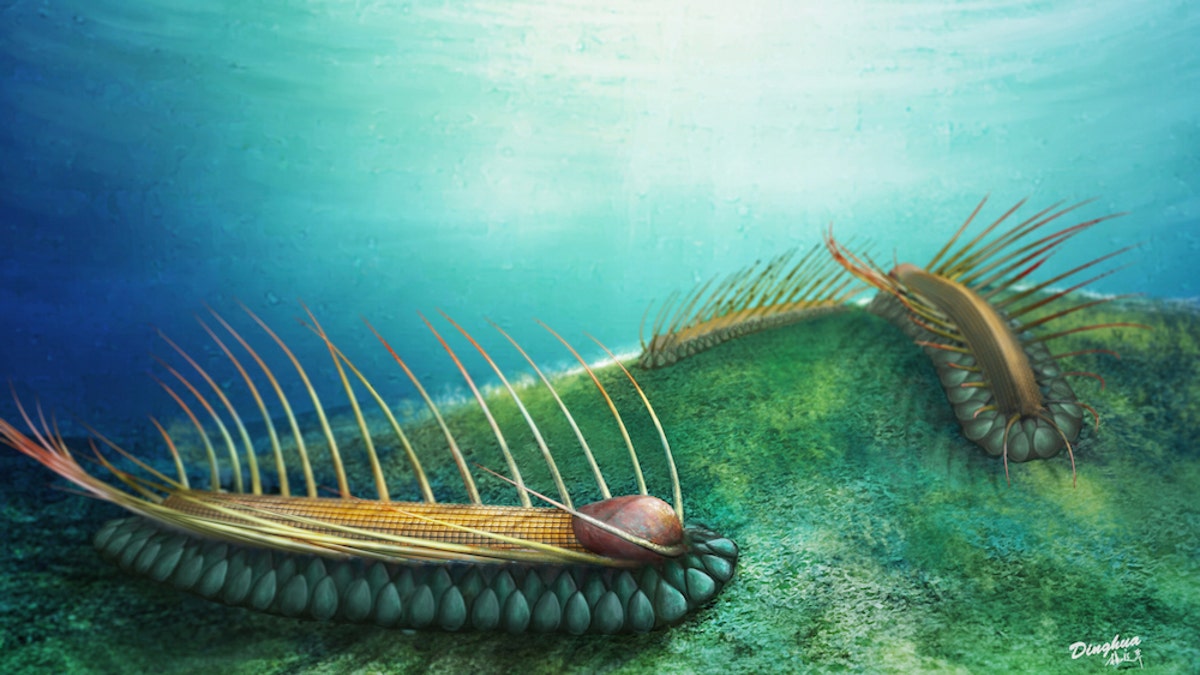

An artist's interpretation of the spiky <i>Orthrozanclus elongata</i> (Zhao, F. et al. Scientific Reports. 2017.)

About 515 million years ago, a tiny sea critter that was "strange beyond measure" wasn't taking any chances with its safety: Armor covered its back and sides, a helmet-like shell protected its head, and pointy spikes stuck out from its sides, researchers have found.

"The creature is like a mythical beast," said study researcher Martin Smith, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at Durham University in England.

The newfound beast may change scientists' understanding of the behavior of some of these early Cambrian period animals, the researchers said. [Cambrian Creatures Gallery: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

New discovery

The researchers discovered two specimens of the creature in the Cambrian Chengjiang biota, a famous fossil site in southwest China. Study lead researcher Fangchen Zhao, a paleobiologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found one specimen in 2015, and an amateur fossil collector unearthed another, giving it to Zhao in 2016.

It's incredible that the teeny, slug-like critter was discovered at all. It's only about 0.7 inches (20 millimeters) long and 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) wide, Smith said. Given that the two specimens are similar in size, they're both likely full-grown adults, he noted.

"These fossils are incredibly rare," Smith told Live Science. "Only two specimens have been found, amidst the tens of thousands of other creatures known from the same deposits."

The scientists named the newfound species Orthrozanclus elongata. The species name alludes to the creature's elongated body, the researchers wrote in the study.

Armor and spikes

An examination of O. elongata showed that it's covered with a coat of armor. Rows of scales, much like roof tiles, cover its back, and overlapping, leaf-like plates protect its sides, Smith said.

"But most prominent are the cocktail-stick-like spines that emerge from its sides like the rays of a sunburst," Smith said. The spines are longer than the animal is wide and give it the appearance of a cuddly cactus, Smith joked. [See images of another bizarre Cambrian creature]

"Odder still, its head is covered by a small shell, almost as if it's wearing a bike helmet," Smith said. "We don't know much about the animal underneath these mineralized plates — whether it had legs or a slug-like foot, [and] whether it had teeth or tentacles."

The "beautifully preserved armor" of O. elongata may provide clues about the anatomy of the tommotiids, relatives of the brachiopods (also called lampshells). Most tommotiid fossils don't show the whole animal, just isolated scales and plates. However, it appears that O. elongata is a close match to the shapes and proportions of certain tommotiid species, Smith said.

If the tommotiids — and by extension brachiopods — were similar to O. elongata during the Cambrian, then it's possible that they had extensive armor at that time, as well as the ability to actively move around the sea, searching for food, Smith said.

Nowadays, brachiopods are sedentary creatures that stick to the seafloor, hide in their shells and filter bits of food out of seawater. Some people think of the creatures as "living fossils," but "if our interpretations are right, they would turn this idea on its head," Smith said. "Whereas many lineages show evolutionary trends towards greater activity and complexity, brachiopods seem to have settled down to a sedentary existence, like a retiree settling down in a favorite armchair." [Photos: Ancient Marine Critter Had 50 Legs, 2 Large Claws]

Family-tree checkup

The study shows that Orthrozanclus, a genus previously known only from Canada's Burgess Shale, also lived in what is now China, said Derek Briggs, a professor of paleontology at Yale University, who was not involved in the study.

This argument that brachiopods were once active and then settled down later in their evolution would be stronger if the researchers had done a phylogenetic (family tree) analysis, said Briggs and Javier Ortega-Hernandez, a research fellow in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge, in the United Kingdom, who was not involved with the study.

"Then again, the authors are tackling a notoriously difficult region of the tree of life that even cutting-edge molecular studies have not been able to fully resolve," Ortega-Hernandez said. "So, it is probably best for now that they put the data out there and make it available so that future studies can build upon their findings."

The study was published online today in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.