The skeleton was Torrejon Fossil Fauna Area, a remote area in northwestern New Mexico, by Thomas Williamson, Curator of Paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science.

A 62-million- year-old partial skeleton discovered in New Mexico confirms that early primate ancestors preferred to dwell in trees.

The New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science reports that the skeleton was uncovered in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin by Thomas Williamson and his twin sons, Taylor and Ryan. Williamson is the curator of Paleontology at the Museum.

99-MILLION- YEAR-OLD BIRD FOUND PRESERVED IN AMBER STUNS SCIENTISTS

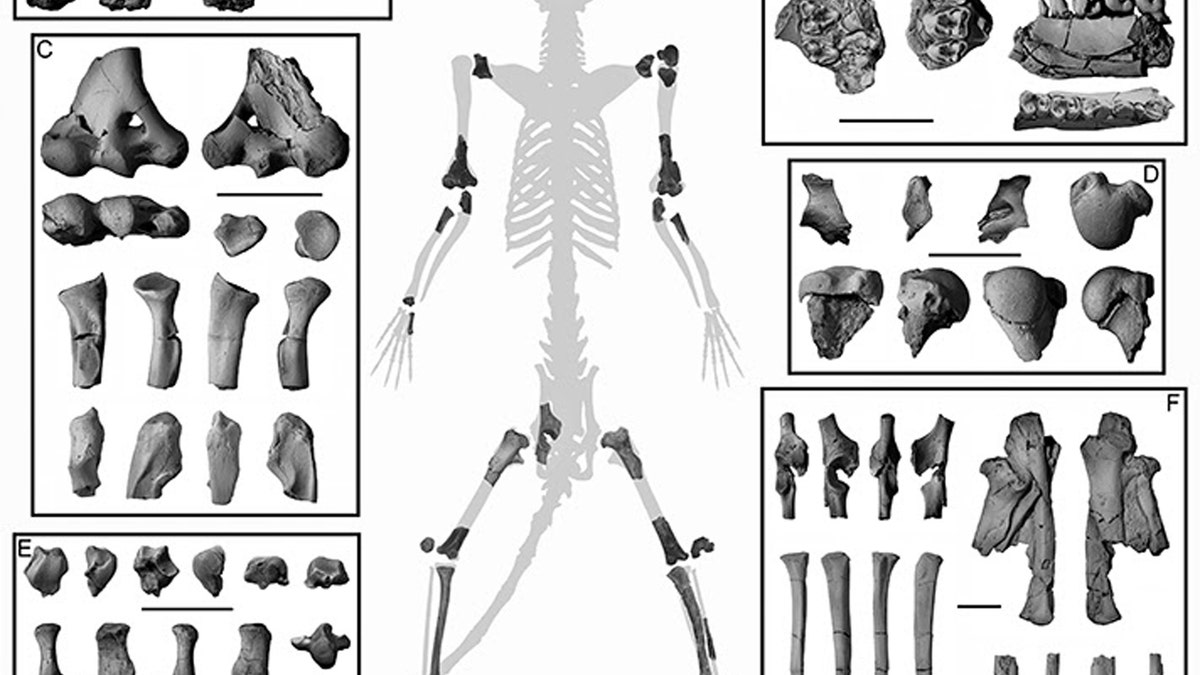

The skeleton is the oldest known primate skeleton and consists of 20 different bones, including the cranium, jaws, teeth and portions of upper and lower limbs, according to the museum. The primate was found to have features that favored living in trees, such as flexible joints used for climbing and clinging to branches.

SCIENTISTS FIND OLDEST KNOWN SPECIMENS OF THE HUMAN SPECIES

Researchers say their findings support the hypothesis that plesiadapiforms were the earliest primates. They make their first appearance in the fossil record just after non-avian dinosaurs became extinct, according to the museum. The new data supports the theory “that all of the geologically oldest primates known from skeletal remains, encompassing several species, were arboreal,” wrote the museum.

Stephen Chester, an assistant professor at Brooklyn College, City University of New York, and curatorial affiliate of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum, said in a press release that the various bones comprising the discovery provide a new window into primate details.

“We now have anatomical evidence from the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle joints that allows us to assess where these animals lived in a way that was impossible when we only had their teeth and jaws," Chester noted.

Eric Sargis, professor of Anthropology at Yale University, and a co-author of the study added that palaechthonids and other plesiadapiforms had outward-facing eyes and relied on smell more than living primates do today, which suggests that plesiadapiforms are “transitional between other mammals and modern primates,” wrote the museum.

“To find a skeleton like this, even though it appears a little scrappy, is an exciting discovery that brings a lot of new data to bear on the study of the origin and early evolution of primates,” said Sargis.

The findings were published in the May 31, 2017, online edition of "Royal Society Open Science."