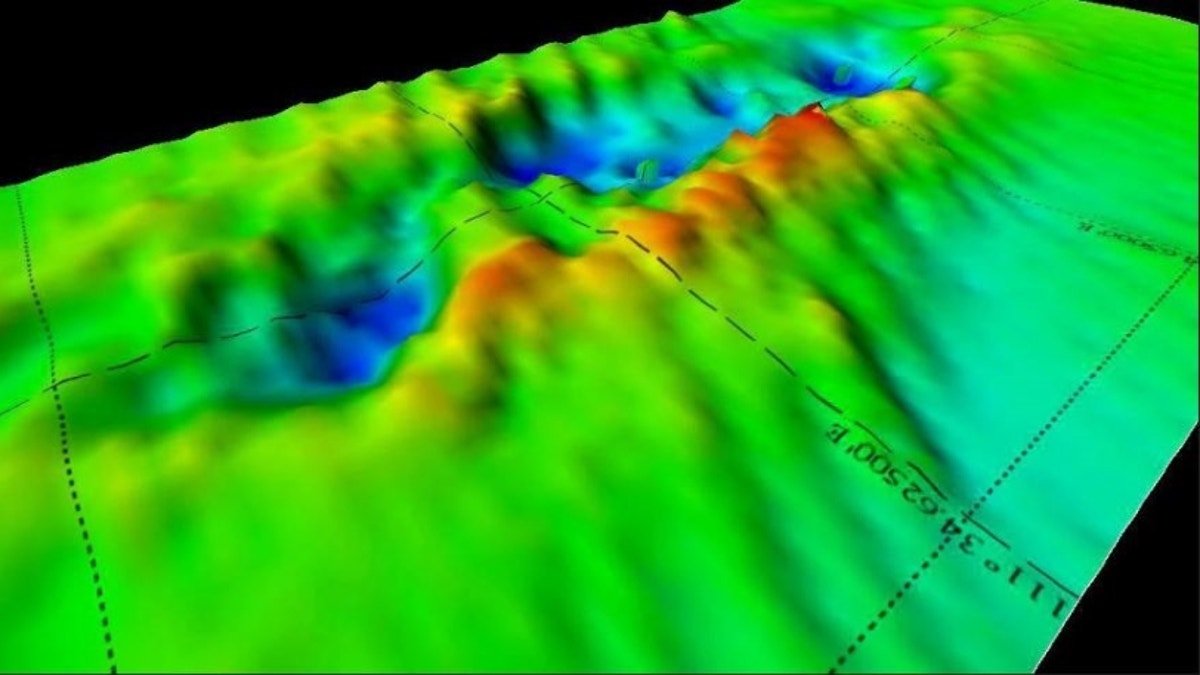

A 3D sonar scan of the remains of British warship HMS Electra, one of several war wrecks in the Java Sea thought to have been plundered by metal scavenging operators. (nswwrecks.info)

Illegal salvagers have plundered at least six World War II shipwrecks near Indonesia for scrap metal, including the wreck of an American submarine that has now "completely vanished," according to investigators.

The damaged wrecks include three Dutch and two British warships sunk by Japanese forces after the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942, and the American submarine USS Perch, which sank in the Java Sea in March 1942 after being damaged in an attack on Japanese destroyers.

The scale of damage to the historic shipwrecks was discovered early this month by an international team of divers and underwater survey specialists, sponsored by a Dutch naval memorial society, the Karel Doorman Fund. The fund had hoped to capture video footage of the Dutch shipwrecks in preparation for the 75th anniversary of the Battle of the Java Sea next year. [See Photos of the Historic WWII-Era Shipwrecks in the Java Sea]

The Dutch wrecks were almost intact when they were rediscovered by amateur divers in 2002, but the latest expedition found only holes in the seabed where many of the wrecks once lay.

"It was shocking," Jacques Brandt, president of the Karel Doorman Fund, told Live Science. "As the representative organization of the next-of-kin [of the ships' crews], it was a big blow to us, as we considered those ships as being war graves under the sea and they clearly should not be tampered with."

More from Live Science

The survey team reported that the wrecks of two of the Dutch warships the HNLMS De Ruyter and the HNLMS Java appear to be missing. A large part of a third wreck the HNLMS Kortenaer is also missing.

They also reported that two British war wrecks in the area the HMS Exeter and the HMS Encounter have been almost entirely scavenged for scrap metal, and that the wreck of the USS Perch has "completely vanished."

Wrecking history

The Java Sea survey report has now been turned over to the Dutch defense ministry, which is in charge of protecting the nation's naval wrecks, Brandt said.

"It is a very serious offence if the wrecks have been deliberately removed, but before we make that conclusion the authorities will have to make further investigations," he said.

The Dutch defense minister made a statement to members of Parliament last week, noting the destruction reported by the expedition to the Java Sea wrecks.

Britain's defense ministry also issued a statement in response to the expedition's report, condemning the damage and desecration done to the wrecks and suggesting that illegal metal salvagers are to blame.

Under international agreements, naval vessels remain the property of their governments after they sink, and it is illegal to disturb or salvage them without official permission, said marine archaeologist Innes McCartney, a visiting research fellow at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom.

But a "perfect storm" of high metal prices and a lack of enforcement has resulted in many wartime shipwrecks being broken up for scrap metal by illegal salvagers, especially in the Asia and Pacific regions, he said.

"There has been anecdotal evidence for an abundance for years that shipwrecks in the area of the Battle of the Java Sea have been getting hammered by salvage companies," McCartney told Live Science. "From my standpoint it's incredibly frustrating. We will now never be able to archaeologically study the Battle of the Java Sea — it's gone, it's lost to us forever."

Metal pirates

Suspicion surrounding the destruction of the Java Sea war wrecks has fallen on a number of salvage ships operating in Southeast Asian waters, McCartney said. They include a Mongolian-flagged salvage barge that was photographed last year taking metal from a popular scuba diving wreck near Singapore, according to Underwater Photography Guide News (UWPG News).

Illegal salvagers are also thought to be responsible for recent damage to the wrecks of the British warships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales, which were sunk by Japanese aircraft near Malaysia's Tioman Island in 1941, and the illegal salvage of a Dutch submarine wreck, the HNLMS 0-16, in the Gulf of Thailand in 2012, reported the New Strait Times.

The U.S. Navy reported last year that the wreck of the American cruiser USS Houston, which sank in February 1942 in the Sunda Strait, southwest of the Java Sea, with around 650 sailors and marines onboard, had also suffered "unauthorized disturbance of the grave site."

McCartney said the salvage barge photographed near Singapore last year appeared to be equipped with a large crane and a 5-ton "drop chisel," which is designed to cut a shipwreck apart.

"What they're doing is just dropping it down on the wreck, chopping the wreck into manageable pieces, and then using that crane to haul it on board," he said.

Similar equipment was used by some Dutch salvage operators in recent years to remove especially valuable metals, like brass, from British shipwrecks that were sunk at the Battle of Jutland in the North Sea in 1916, McCartney said.

Although researchers have identified and documented the salvage firms responsible for much of the damage to the Jutland wrecks, so far the Dutch authorities have taken no action, he said.

Eyes in the sky

Radio beacons and satellite radar technology now make it possible to track salvage ships in the same way that many fishing trawlers are now tracked to prevent illegal fishing, McCartney said. Salvage ships that are seen to linger over known shipwrecks, or that exhibit other suspicious behavior, can be flagged automatically and inspected when they reach port, he said.

McCartney also noted that a growing number of countries have agreed to mutually protect shipwrecks in their waters under the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

But, several leading countries — including the U.S. and the U.K. — have not ratified the convention, out of concern that it will be too difficult or expensive to enforce, he said.

McCartney said, however, that modern methods of enforcement are mostly electronic, and don’t require sending warships to physically protect the shipwrecks.

"The legal framework is there, and the technological framework is there — it just requires the countries of the world to get on and do it," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Copyright 2016 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.