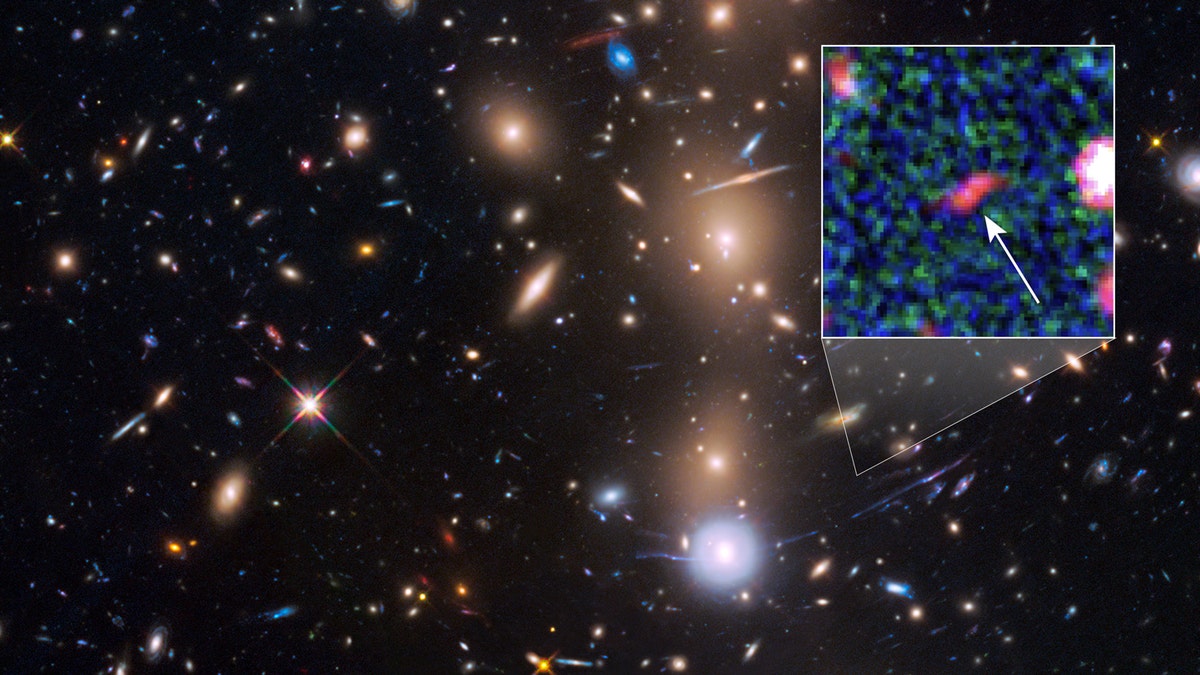

This is a Hubble Space Telescope view of a very massive cluster of galaxies, MACS J0416.1-2403, located roughly 4 billion light-years away and weighing as much as a million billion suns. (NASA, ESA, and Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile)

Astronomers using NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescope have found what they believe is the faintest object ever seen in the early universe, a galaxy that existed 13.8 billion years ago or about 400 million years after the big bang.

Nicknamed Tayna, meaning “first-born” in Aymara, a language spoken in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America, the object could offer clues into the formation and evolution of the first galaxies. It also suggests that the early universe could be rich in galaxy targets for the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to uncover.

Related: Hubble space telescope captures stunning image of barred spiral galaxy

“Thanks to this detection, the team has been able to study for the first time the properties of extremely faint objects formed not long after the big bang,” Leopoldo Infante, an astronomer at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and the lead author on a study of the discovery that was published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal,, said in a statement.

The remote object is similar in size to the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a diminutive satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. It is making stars at a rate 10 times faster than the LMC, researchers said, leading to a belief that Tayna will likely evolve into a full-sized galaxy.

Related: NASA honors Hubble's 25th anniversary with high-def version of iconic image

The galaxy was spotted as part of Hubble’s Frontier Fields program, which observed a very massive cluster of galaxies, MACS J0416.1-2403, located roughly 4 billion light-years away and weighing as much as a million billion Suns. This giant cluster acts as a powerful natural lens by bending and magnifying the light of far-more-distant objects behind it. Like a zoom lens on a camera, the cluster’s gravity boosts the light of the distant protogalaxy to make it look 20 times brighter than normal and thus easier to spot these young galaxies.

Related: Stars in distant galaxies found to have a pulse

The distance of this newly-discovered galaxy was estimated by building a color profile from combined Hubble and Spitzer observations. The expansion of the universe causes the light from distant galaxies to be stretched or reddened with increasing distance as does the absorption by intervening, intergalactic hydrogen. The infrared wavelengths of these new stars, which appear blue-white, are also measurable by Hubble and Spitzer.