Denver working on 'water bank' to help fight future droughts

If approved project would create an underground reserve of water the size of Connecticut

On a recent weekday in Denver a massive drilling rig bored a hole deep beneath the city.

"We plan to go at least about 2,100 feet at this site," explained Cortney Brand, Project Manager with Leonard Rice Engineers, the group doing the work for the Denver Water Department.

"We have some idea of what we expect to see based on other bore holes that have been completed,” Brand said.

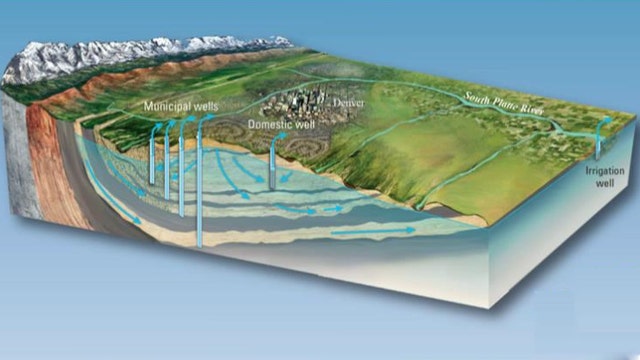

Denver Water is exploring the feasibility of pumping water far under the city, into the massive Denver Basin aquifer system to keep it there until the next dry spell.

As Denver Water Resource Engineer Bob Peters points out, in the already arid American West, "Drought is always on the horizon. We only get 15 inches of rainfall a year here in Denver, and most of our water comes from the mountain snowpack."

That mountain snowpack melts and runs downstream, supplying water for much of the nation including the parched Southwest. When the snowpack fails the effects reach far beyond the region according to Doug Kenney, Director of the Western Water Policy Center at University of Colorado Law School.

"The California drought has really illustrated to people why drought in the West is important. If you consume vegetables in winter, you're probably getting those from Southern California,” Kenney said.

“So from farm products to general economic health, not only do these things resonate throughout the rest of the country but throughout the rest of the world."

A secondary source of water comes from underground aquifers which nature filled over the course of millions of years, and which humans are draining at a massive rate.

Even though the aquifer system under the city of Denver covers an area the size of the Connecticut, Peters said, "The Denver Basin ground water is non-renewable so if you pump that water it's gone. What we're talking about is taking our renewable water supplies and injecting them into the aquifer to keep the aquifer replenished."

With core samples taken every 10 feet down, the bore holes being drilled beneath Denver will provide geologic data about how well the various open bowls in the rock will hold water without losing any to seepage or cracks.

Cities like Phoenix, Wichita and San Antonio are already banking water underground and because it doesn't have the same downsides as above-ground reservoirs the method will surely become more common.

"Reservoirs are really tough to build, politically and financially," Kenney said, “And the loss to evaporation can be enormous.”

"That's especially helpful if you're thinking of putting water underground...for drought. I mean, fifteen years with no evaporation is really a nice selling point to this tool."

If all goes well, Denver will begin taking snowpack runoff and pumping into the underground basin within the next year or two.