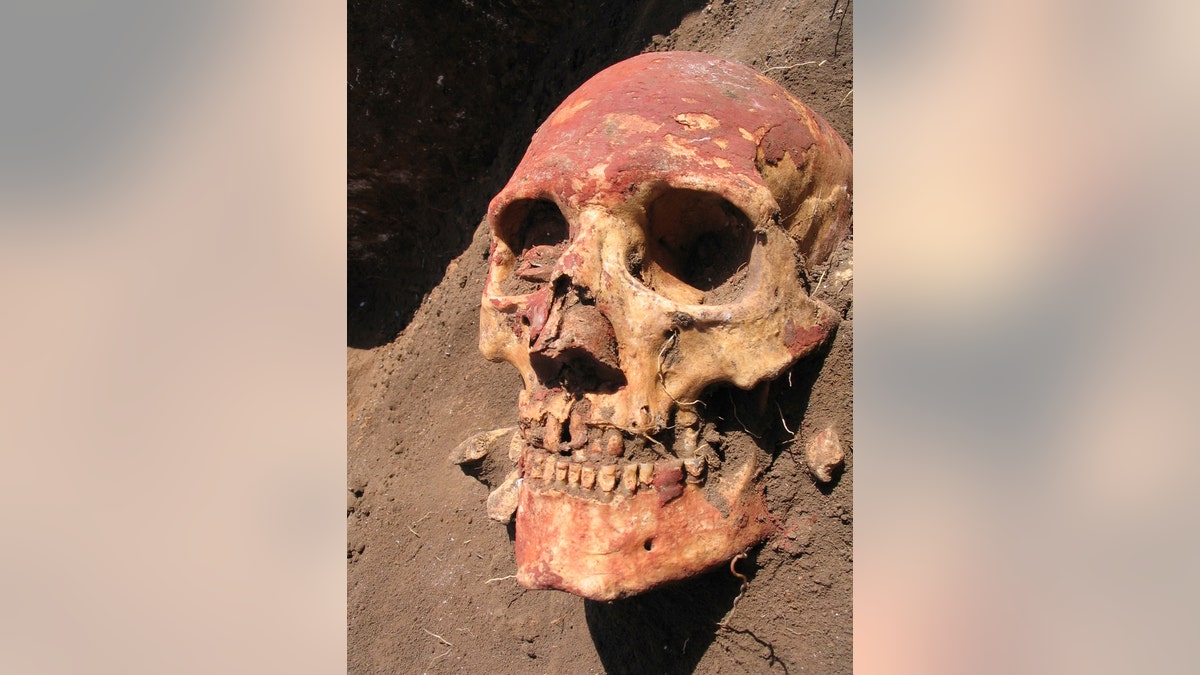

In this undated photo released by Cell journal, a Bronze Age human skull painted with red ochre, from the Yamnaya culture of Central Asia, one of the cultures that carried the early strains of plague. (Simon Rasmussen/Cell 2015 via AP)

The plague was spreading nearly 3,000 years before previously thought, scientists say after finding traces of the disease in the teeth of ancient people — a discovery that could provide clues to how dangerous diseases evolve.

To find evidence of the prehistoric infection, researchers drilled into the teeth of 101 individuals who lived in Central Asia and Europe some 2,800 to 5,000 years ago. The drilling produced a powder that the researchers examined for DNA from plague bacteria. They found it in samples from seven people.

Before the study, the earliest evidence of the plague was from A.D. 540, said Simon Rasmussen of the Technical University of Denmark. He and colleagues found it as early as 2,800 B.C.

"We were very surprised to find it 3,000 years before it was supposed to exist," said Rasmussen, one of the study authors. The research was published online Thursday in the journal, Cell.

Rasmussen said the plague they found was a different strain from the one that caused the three known pandemics, including the Black Death that swept across Medieval Europe. In contrast to later strains, including the one estimated to have wiped out about half of Europe, the Bronze Age plague revealed by the new study could not be spread by fleas because it lacked a crucial gene. So it was probably less able to infect people over wide regions.

But Rasmussen said knowing that plague existed thousands of years earlier than had been believed might explain some unsolved historical mysteries, including the "Plague of Athens," a horrifying unknown epidemic that struck the Greek capital in 430 B.C. It killed up to 100,000 people during the Peloponnesian War.

"People have been speculating about what this was, like was this measles or typhus, but it could well have been plague," Rasmussen said.

He said tracking how the plague evolved from being an intestinal infection to "one of the most deadly diseases ever encountered by humans" could help scientists predict the disease's future path.

"Typically, things get less virulent with time, but that's not always the case," said Hendrik Poinar, a molecular evolutionary geneticist at McMaster University in Canada who was not part of the study. He noted that diseases could acquire new features — including lethality — relatively quickly.

Other experts said it was unlikely that plague would ever pose as great a threat as it has in the past, especially since it is now largely treatable.

"It might be that (plague) will eventually burn itself out," said Brendan Wren, dean of the faculty of infectious and tropical diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Wren said other diseases like leprosy have also lost genes over time and are now less able to sicken people.

"The evidence is that (plague) is not going to come back big time, but it's hard to predict what the bacteria will do," he said. "They are great survivors."