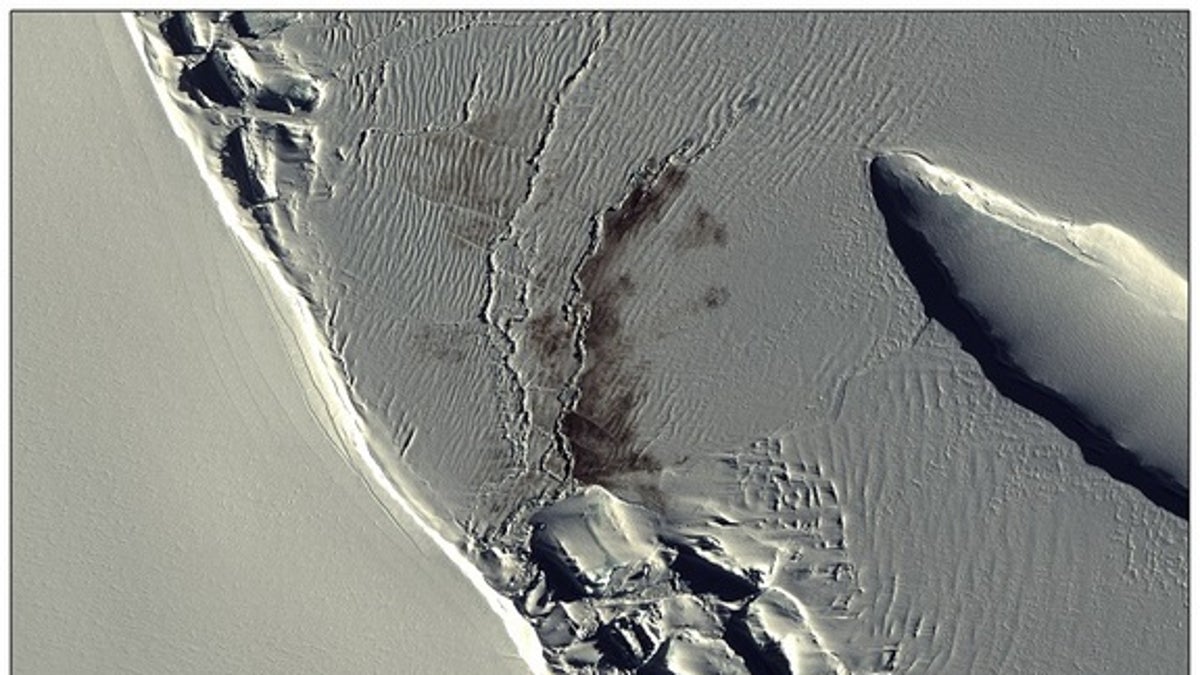

Researchers can spot penguin colonies thanks to the large poop stains they leave on the ice. (Digital Globe, Inc)

In the face of rising temperatures, emperor penguins in Antarctica may be forced to find new breeding grounds instead of returning to the same spot to mate year after year, new research finds.

Scientists are tracking this climate-driven march by studying the penguins' poop stains; in satellite images, the birds' dark droppings against a gleaming white backdrop of ice reveal their every move.

Emperor penguins are a philopatric species, meaning they return to the same spot each year to breed. When confronted with rising temperatures and receding ice sheets, however, the penguins may forgo their philopatric nature. [Images: The Emperor Penguins of Antarctica]

Michelle LaRue, a research fellow at the Polar Geospatial Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, first noticed that the penguins might be adapting to their changing environment when she came across a new colony about 120 miles south of a breeding ground that was abandoned when the ice disappeared.

"I thought, 'Well, maybe they just moved,'" LaRue told Live Science.

She began looking through satellite images and data from other colonies to see if the species was actually traveling around. New satellite-imagery technology makes it easy for researchers to track the penguins because of their easy-to-spot poop stains on the Antarctic ice and snow.

"They are the only species living on the very white ice and they leave a very brown stain it's pretty obvious," LaRue said.

LaRue and a team of researchers found evidence that part of the Pointe Gologie colony, made famous by the "March of the Penguins" documentary, may have moved to new breeding grounds.

In the 1970s, the ocean temperature around Antarctica climbed, and simultaneously, the colony size reduced by half. At the time, researchers thought the warming temperatures and receding ice had killed off the penguins. But, the new study shows that part of the colony might have moved to different breeding grounds.

Researchers originally thought the next closest colony was more than 930 miles away. But LaRue and the team found several other colonies within the 930-mile-radius that the members of the Pointe Gologie group could have easily reached.

This is not the first time emperor penguins have shown new behavior that might help protect them from climate change. Scientists have observed emperor penguins climbing cliffs to reach ground still covered with ice that is suitable for breeding.

LaRue said the study is only an observation and more research is needed to confirm that the colonies are shifting. Placing trackers on more penguins and conducting genetic studies of colonies could provide some insight into how much the species is moving, she said.

The findings suggest penguins may be in better shape to survive than previously thought, but the flightless birds and other Antarctic species are still in danger from warmer temperatures.

"The study is not saying climate change isn't happening," LaRue said. "It just means maybe we need to start paying more attention to colony fluctuations."

The new study was presented at the Ideacity conference in Toronto on June 20, and will be published in the journal Ecography.