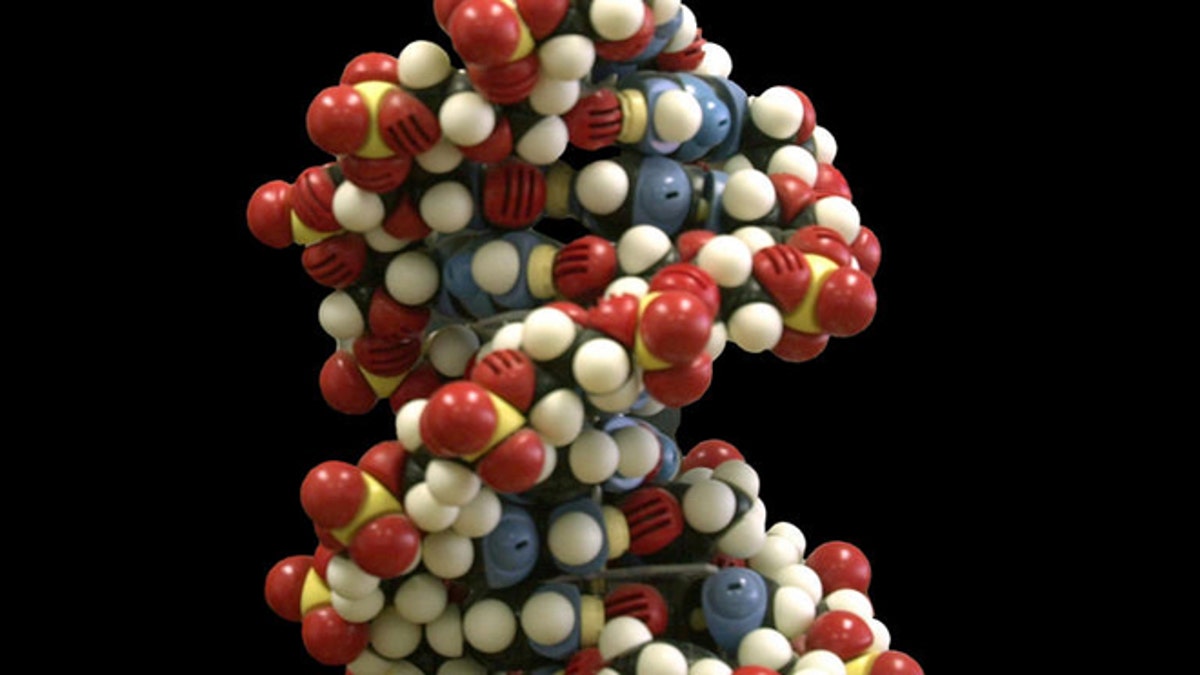

(AP GraphicsBank)

Scientists have long believed that DNA tells the cells how to make proteins. But the discovery of a new, second DNA code overnight suggests the body speaks two different languages.

The findings in the journal Science may have big implications for how medical experts use the genomes of patients to interpret and diagnose diseases, researchers said.

The newfound genetic code within deoxyribonucleic acid, the hereditary material that exists in nearly every cell of the body, was written right on top of the DNA code scientists had already cracked.

[pullquote]

Rather than concerning itself with proteins, this one instructs the cells on how genes are controlled.

Its discovery means DNA changes, or mutations that come with age or in response to viruses, may be doing more than what scientists previously thought, he said.

"For over 40 years we have assumed that DNA changes affecting the genetic code solely impact how proteins are made," said lead author John Stamatoyannopoulos, University of Washington associate professor of genome sciences and of medicine.

"Now we know that this basic assumption about reading the human genome missed half of the picture," he said.

"Many DNA changes that appear to alter protein sequences may actually cause disease by disrupting gene control programs or even both mechanisms simultaneously."

Scientists already knew that the genetic code uses a 64-letter alphabet called codons.

But now researchers have figured out that some of these codons have two meanings. Coined duons, these new elements of DNA language have one meaning related to protein sequence and another that is related to gene control.

The latter instructions "appear to stabilise certain beneficial features of proteins and how they are made," the study said.

The discovery was made as part of the international collaboration of research groups known as the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements Project, or ENCODE.

It is funded by the US National Human Genome Research Institute with the goal of finding out where and how the directions for biological functions are stored in the human genome.

Get more science and technology news at news.com.au.