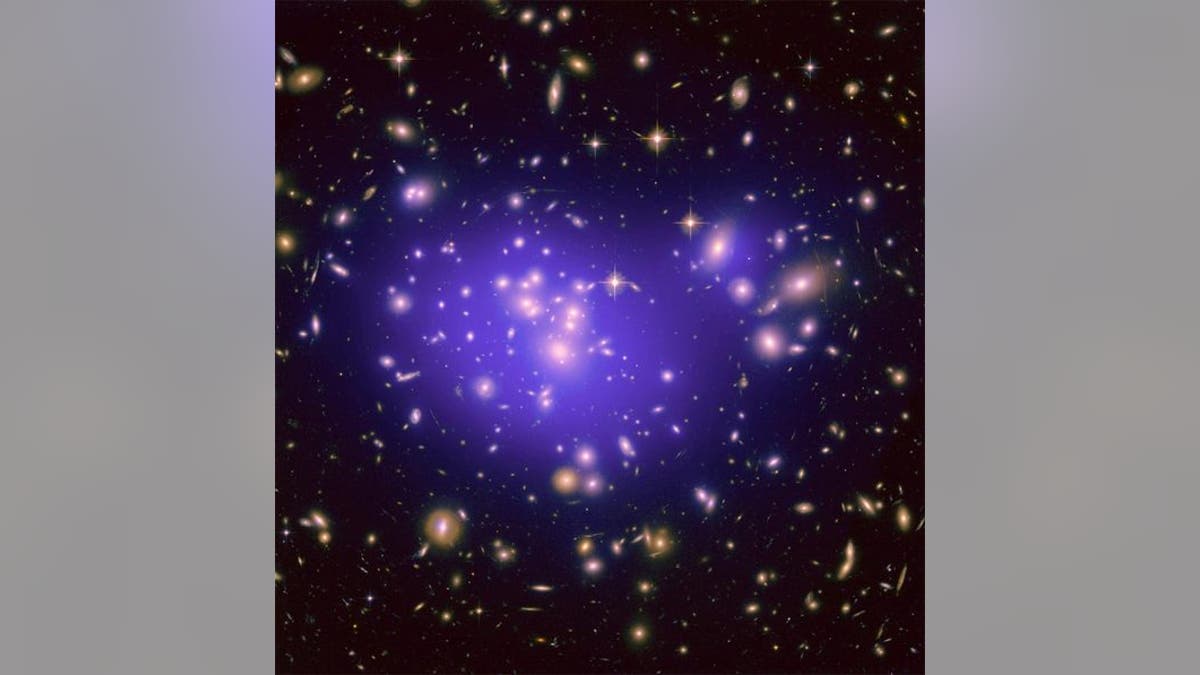

The galaxy cluster Abell 1689 is famous for the way it bends light in a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. A new study of the cluster is revealing secrets about how dark energy shapes the universe. NASA, ESA, E. Jullo (JPL/LAM), P. Natarajan (Yale) and J-P. Kneib (LAM) (NASA, ESA, E. Jullo (JPL/LAM), P. Natarajan (Yale) and J-P. Kneib (LAM))

A new study of one of the universe's fundamental constants casts doubt on a popular theory of dark energy, scientists say.

Dark energy is the name given to whatever is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate. One theory predicts that an unchanging entity pervading space called the cosmological constant, originally suggested by Albert Einstein, is behind dark energy. But a popular alternative, called rolling scalar fields, suggests that whatever's causing dark energy isn't a constant, but has changed through time.

If that were true, though, it should have caused the values of other fundamental constants of nature to change, too. And a new measurement of one such constant, the ratio between the mass of the proton and mass of the electron, shows that this constant has remained remarkably steady over time.

The proton and the electron are two fundamental particles that make up the atoms inside stars, galaxies and people. Recently, a team of astronomers used the German Effelsberg 100-meter radio telescope to observe alcohol molecules in a distant galaxy, and found that the protons and electrons in those molecules' atoms weigh about the same as the ones right here on Earth.

Because the galaxy they studied lies 7 billion light-years away, its light has taken that long (7 billion years) to travel to Earth, and thus we are seeing it as it was half the universe's lifetime ago. (The universe is thought to be about 13.7 billion years old.) The observations strongly suggest that this fundamental constant has remained mostly unchanged over the past 7 billion years. [The Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps ]

Building on that finding, which was detailed in the Dec. 14 issue of the journal Science, University of Arizona astronomer Rodger Thompson calculated how much the proton-to-electron mass ratio would change over time if the rolling scalar fields theory were true. He found that the predictions did not match the data.

That result supports the idea of Einstein's cosmological constant. "Basically, it says alternatives to Einstein's theory are really running out of room here," Thompson said Jan. 9 during a press conference at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Long Beach, Calif., where he presented his work. "This puts some very serious constraints on these rolling scalar field cosmologies."

However, the cosmological constant theory isn't ideal, either. The expected value of the constant, based on known physics, is a number more than 10 to the power of 60 (one followed by 60 zeros), which is too large to explain the universe as we see it.

And the new findings don't drive nails into the coffins of other dark energy explanations, either.

"Rolling scalar fields are not dead," Thompson said. Rather, "they may be more complicated than those original models expected."

The new study is the second in about a week to back up Einstein. Another project, also presented at the AAS meeting, offered support for the idea that space-time is fundamentally smooth, as predicted by the early 20th-century genius, as opposed to foamy.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also onFacebook & Google+.