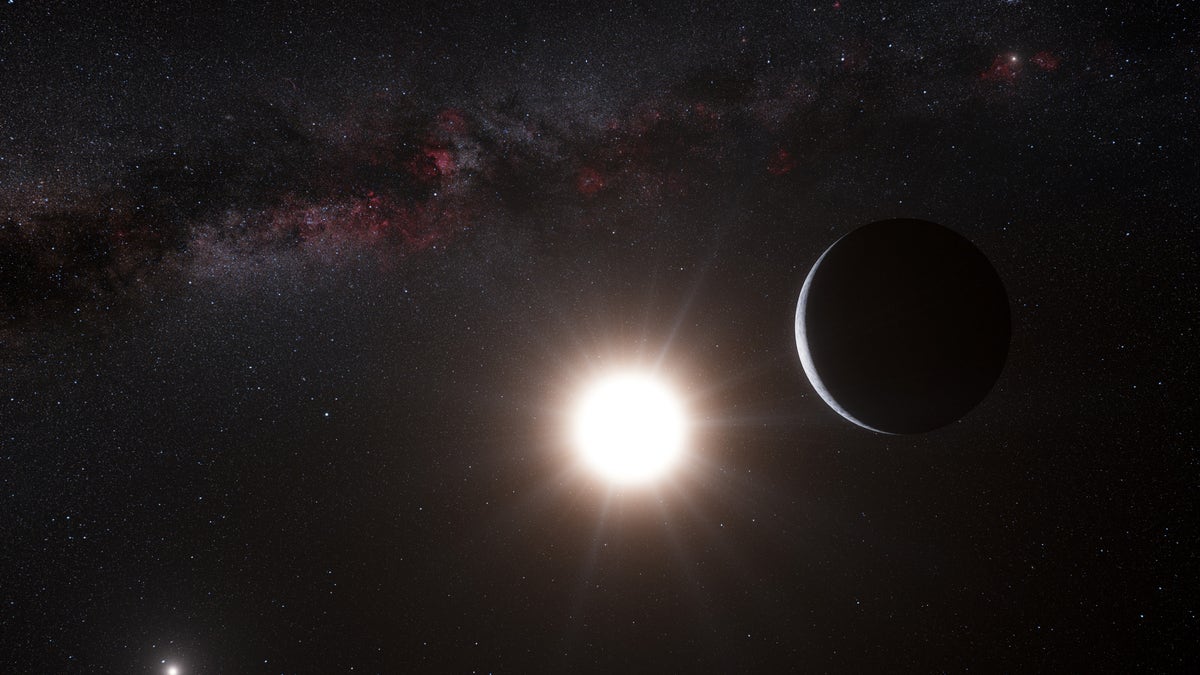

Oct. 16, 2012: This artists impression made available by the European Southern Observatory shows a planet, right, orbiting the star Alpha Centauri B, center, a member of the triple star system that is the closest to Earth. Alpha Centauri A is at left. The Earth's Sun is visible at upper right. (AP)

WASHINGTON – European astronomers say that just outside our solar system they've found a planet that's the closest you can get to Earth in location and size.

It is the type of planet they've been searching for across the Milky Way galaxy and they found it circling a star right next door -- 25 trillion miles away. But the Earth-like planet is so hot its surface may be like molten lava. Life cannot survive the 2,200 degree heat of the planet, so close to its star that it circles it every few days.

The astronomers who found it say it's likely there are other planets circling the same star, a little farther away where it may be cool enough for water and life. And those planets might fit the not-too-hot, not-too-cold description sometimes call the Goldilocks Zone.

That means that in the star system Alpha Centauri B, a just-right planet could be closer than astronomers had once imagined.

It's so close that from some southern places on Earth, you can see Alpha Centauri B in the night sky without a telescope. But it's still so far that a trip there using current technology would take tens of thousands of years.

But the wow factor of finding such a planet so close has some astronomers already talking about how to speed up a 25 trillion-mile rocket trip there. Scientists have already started pressuring NASA and the European Space Agency to come up with missions to send something out that way to get a look at least.

The research was released online Tuesday in the journal Nature. There has been a European-U.S. competition to find the nearest and most Earthlike exoplanets -- planets outside our solar system. So far scientists have found 842 of them, but think they number in the billions.

While the newly discovered planet circles Alpha Centauri B, it's part of a system of three stars: Alpha Centauri A, B and the slightly more distant Proxima Centauri. Systems with two or more stars are more common than single stars like our sun, astronomers say.

This planet has the smallest mass -- a measurement of weight that doesn't include gravity -- that has been found outside our solar system so far. With a mass of about 1.1 times the size of Earth, it is strikingly similar in size.

Stephane Udry of the Geneva Observatory, who heads the European planet-hunting team, said this means "there's a very good prospect of detecting a planet in the habitable zone that is very close to us."

And one of the European team's main competitors, Geoff Marcy of the University of California Berkeley, gushed even more about the scientific significance.

"This is an historic discovery," he wrote in an email. "There could well be an Earth-size planet in that Goldilocks sweet spot, not too cold and not too hot, making Alpha Centauri a compelling target to search for intelligent life."

Harvard planet-hunter David Charbonneau and others used the same word to describe the discovery: "Wow."

Charbonneau said when it comes to looking for interesting exoplanets "the single most important consideration is the distance from us to the star" and this one is as close as you can get. He said astronomers usually impress the public by talking about how far away things are, but this is not, at least in cosmic terms.

Alpha Centauri was the first place the private Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence program looked in its decade-long hunt for radio signals that signify alien intelligent life. Nothing was found, but that doesn't mean nothing is there, said SETI Institute astronomer Seth Shostak.

The European team spent four years using the European Southern Observatory in Chile to look for planets at Alpha Centauri B and its sister stars Alpha Centauri A and Proxima Centauri. They used a technique that finds other worlds by looking for subtle changes in a star's speed as it races through the galaxy.

Part of the problem is that the star is so close and so bright -- though not as bright as the sun -- that it made it harder to look for planets, said study lead author Xavier Dumusque of the Geneva Observatory.

One astronomer who wasn't part of the research team, wondered in a companion article in Nature if the team had enough evidence to back such an extraordinary claim. But other astronomers said they had no doubt and Udry said the team calculated that there was only a 1-in-1,000 chance that they were wrong about the planet and that something else was causing the signal they saw.

Finding such a planet close by required a significant stroke of good luck, said University of California Santa Cruz astronomer Greg Laughlin.

Dumusque described what it might be like on this odd and still unnamed hot planet. Its closest star is so near that it would always hang huge in the sky. And whichever side of the planet faced the star would be broiling hot, with the other side icy cold.

Because of the mass of the planet, it's likely a rocky surface like Earth, Dumusque said. But the rocks would be "more like lava, like a lava planet."

"If there are any inhabitants there, they're made of asbestos," joked Shostak.