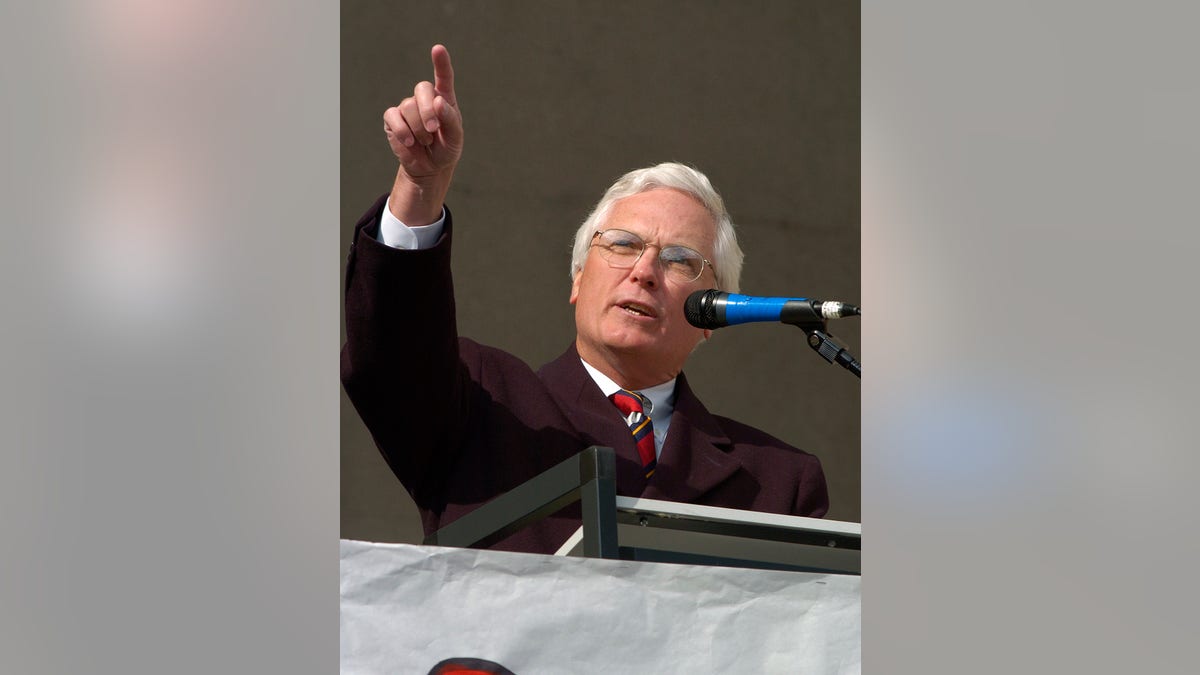

Former Jefferson County and District Court Judge Michael O'Connell gestures towards the Jefferson County Courthouse during a rally Sunday April 24, 2005 at in Louisville, Ky. The rally was held to counter the Justice Sunday rallies held today. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

LOUISVILLE, Ky. – A Kentucky politician has drawn the ire of his subordinates for his quick temper and expectation of political support from employees in the form of their cash. These contributions, according to some, are the product of a pattern of coercion and retribution that is unethical and a “blatant violation of the law.”

Four former employees of Jefferson County Attorney Mike O’Connell have described to Fox News a culture of duress in O’Connell’s office, where they witnessed him consulting donor lists before considering employees for promotions.

Glenda Bradshaw, a high-ranking former prosecutor in the office, filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against O’Connell after she was fired, claiming in the suit that some employees donate to his campaign out of fear of “his wrath.”

All employees who spoke to Fox News detailed similar expectations of loyalty to the Democrat in the form of cash or check.

In an emailed statement responding to this article O'Connell said through a spokesperson: “I am thankful for the campaign support I have received from all walks of our community. I am humbled that some of my staff have supported my re-election because they know firsthand the good work we perform daily."

Before his 2008 appointment to the position, O’Connell served as both a district and circuit court judge in Kentucky.

Kara Lewis, a former attorney in O’Connell’s office, claims she was fired for no reason beyond her refusal to contribute to O’Connell’s campaign. Her firing, during which she was pulled from a courtroom and told she would no longer be working cases, threw her family’s plans into tumult and doubt.

“It affected my career, it affected my family,” Lewis said. “It had a horrible effect on my life. … It had a horrible impact on us financially.”

“When he was interviewing me, he would have already seen that I was not on any contribution lists.”

Lewis was terminated one month after O’Connell’s re-election in 2010 after working five years in the office. At the time, she and her husband Todd were looking for houses and thinking about having children.

“I never had any sort of disciplinary things,” she said. “I was a good prosecutor and they gave me no reason. They gave me no explanation, no nothing. Just, ‘you’re not being rehired.’”

In the prior months, Lewis had applied for a supervisory role in the office. She said O’Connell was “openly hostile” during the interview; she believes her refusal to donate was a deciding factor in his decision to deny her the role.

“Before every interview he was going to his secretary and asking to see the contribution list,” Lewis said. “When he was interviewing me, he would have already seen that I was not on any contribution lists.”

The couple decided shortly after O’Connell’s appointment to the position that they would not donate. At the time, Lewis’ husband Todd was involved in enforcing campaign finance laws for former Kentucky Attorney General Jack Conway, and he believed O’Connell’s practices would eventually draw the eye of state or federal authorities.

“We believed, and still believe, that it is illegal for him to coerce campaign donations,” she said. “We fully expected that at some point he would be prosecuted for that because it was such a blatant violation of the law.”

After his wife was fired, Todd Lewis said he took his concerns about O’Connell’s actions to both the FBI and his employer. His proximity to the case would keep him from prosecuting the county attorney, but he felt someone should. Conway told him that his family and O’Connell’s were longtime political allies. No action was ever taken by the highest legal office in the state.

Despite multiple attempts, Conway could not be reached for comment.

O’Connell’s employees have proved to be a lucrative and constant source of cash for his political ambitions over the past decade.

In 2010, the first year the Democrat ran for re-election, his employees amassed $45,018.45 on 103 individual contributions. That represented 30 percent of the total $149,278.68 he pulled in for the primary race, according to campaign finance records.

“It’s illegal for Metro employees to be shaken down. The grey area is that all the laws talk about state and city employees. Mike’s office is a county office.”

The total dollar amount given by his employees dropped to just under $27,000 in 2014. However, the 95 individual donations from them made up 65 percent of the 147 donations included in the filing. O’Connell raised $230,815.03 for the successful re-election.

This year, the silver-haired politician has amassed a campaign war chest of $309,118.13 for his primary battle against local attorney Brent Ackerson. O’Connell returned to the well again, and his employees contributed $45,616.96 -- about 14 percent of that total. They provided the majority of individual donations to the campaign. Of the 189 total donations, members of the Jefferson County Attorney’s Office gave 98, or nearly 52 percent.

As is the case with most incumbent politicians, the remaining balance from one race rolls over into a general campaign fund for the next election cycle.

Ackerson has consistently called O’Connell’s campaign finance practices out in local debates. The attorney also sits on the Louisville Metro Council, and has two years left on his term. He said O’Connell’s actions are certainly unethical, if not illegal.

“It’s illegal for Metro employees to be shaken down,” Ackerson said. “The grey area is that all the laws talk about state and city employees. Mike’s office is a county office.”

For his campaign, Ackerson has accumulated a touch more than $28,000, which includes a $10,000 donation to himself. O’Connell’s employees have outraised him nearly two to one.

Joshua Douglas, a campaign finance expert who is a law professor at the University of Kentucky, said officials can’t require their employees to contribute, but there’s nothing necessarily illegal about a culture of contribution.

“It’s not surprising to me that the people that work for him and presumably support him by working for him would choose to make contributions to his campaign,” Douglas said. “… The devil is in the details, and the question for me is: What are the actual facts?”

O’Connell is a county politician and the rules of the Executive Branch Ethics Commission, which has jurisdiction over state officials, aren’t necessarily the same.

“We hope that the ethics commission on the state level, our conduct would be a gold standard for the counties to follow, but there’s nothing that requires them to follow the same standard we do,” Kathryn Gabhart, executive director of the commission, said.

Although she doesn’t oversee county officials, she said each county is mandated by state law to develop its own code of ethics and review commission. Dana Nickles, council to the Jefferson County Ethics Commission, refused to comment on whether O’Connell’s alleged actions constituted an ethics violation.

However, the county commission’s guidelines state: “No Metro Officer or candidate seeking an office covered by this chapter shall compel any subordinate to participate in an election campaign or ballot referendum, or make a political contribution.”

Additionally, two provisions in the Kentucky Revised Code directly address campaign contributions from an official’s employees. One bars the coercion of votes or donations from state or federal employees. The other states that “no person shall coerce or direct any employee” to vote or contribute to campaigns.

Each law specifically mentions coercion by way of threatening or termination of employment.

Another former employee of O’Connell’s, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation, said the politician’s behavior was a product of the “old-school attorney way.”

“I’m just afraid of the repercussions that would come if he found out that I gave you this information,” the former employee said.

The individual, who was an attorney in the civil division of the office, said O’Connell fostered an anxiety among his employees through his frequent angry outbursts and constant bean counting of his employee’s political contributions.

“I would say there was somewhat a culture of fear,” the former employee said. “You wanted to make sure you didn’t piss Mike off. … It was pretty common knowledge that if you didn’t contribute then they knew about it.”

Fox News has confirmed via campaign finance records that the employee did, in fact, donate to O’Connell at least once. That person said the contributions can take a financial toll, especially on younger staffers who are still climbing the compensatory ladder.

“I didn’t want to be blacklisted or called out for not having contributed,” the former staffer said. “I feared whatever the repercussions were if you didn’t contribute.”

Glenda Bradshaw, who worked in state government for 32 years before she was fired by O’Connell, filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the county attorney in 2010. In the suit, which was eventually dropped, she alleged that O’Connell was “well known to summon the campaign contribution list” when considering employees for promotions and raises. Her lawsuit seemingly corroborates Lewis’ allegations.

“It was a very unpleasant experience,” she said. “… On at least one occasion I witnessed him looking at the list prior to interviewing candidates to be made supervisor.”

Karl Price is another former employee who told Fox News about O’Connell’s anger and expectations of political loyalty. He was hired in 1992 and left in 2015 amid allegations of ethical misconduct in his private practice. Price refused to admit to ethical violations, instead leaving O’Connell’s office to focus full time on his private practice.

“Tense, if you want a single word. It was tense,” Price said. “… Generally I kept my distance, but it was not unusual to hear screaming on that side of the office, and everybody knew that was Mike’s voice.”

O’Connell, who is seeking a third term, would regularly send his employees campaign fundraising literature in the mail, and his secretary would needle people who didn’t act on those flyers. Price said the expected donation was around $200.

Campaign finance records show that Price donated at least $550 to O’Connell between 2011 and 2013.

“My opinion, most of the people felt that it was unethical behavior,” he said. “But their general disposition was they didn’t want to lose their job.”