Cost of membership: Union dues debated at Supreme Court

High Court ruling over worker fees could hurt Big Labor; Shannon Bream reports from Washington.

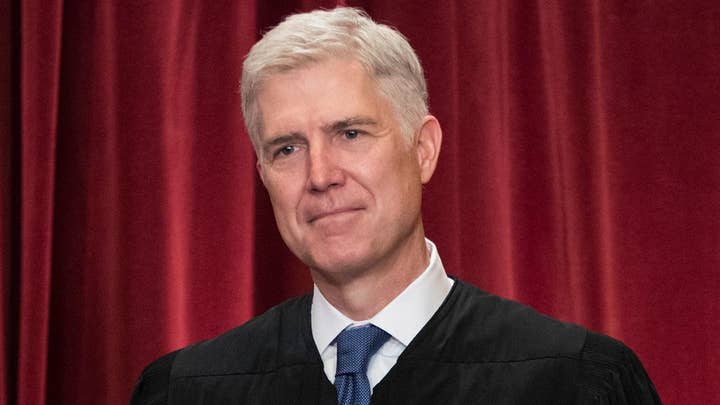

A Supreme Court justice's silence added high drama Monday to an already high-stakes case that could shape the future of America's public-sector unions.

At issue is whether states can compel government workers -- whether they are in a union or not -- to pay fees to support collective bargaining and other activities. The case centers on the complaints of an Illinois state employee who sued, saying he was being asked to support the union's political message.

A ruling against the unions here would deal a major blow to their funding across the country.

Justices split 4-4 on the issue in a similar case two years ago. With Neil Gorsuch now filling the vacancy left by the late Antonin Scalia, he is seen as the deciding vote this time.

But while his colleagues were closely divided in arguments Monday, Gorsuch played it close to the vest. He had no comments or questions from the bench during nearly 70 minutes of oral arguments.

His colleagues were not as shy.

"Not all workers are lawyers. And all they've seen is that this court has suddenly cut legs, at least one, out of the financing of a system that ... some people think it brought labor peace," Justice Stephen Breyer said.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, often a swing justice in other cases, cast a skeptical eye toward the union argument this time. He said repeatedly that separating politics from the union's collective bargaining mission was impossible.

"We're talking here about compelled justification and compelled subsidization of a private party that expresses political views constantly," Kennedy said. He told the union's lawyer, "It seems to me your argument doesn't have much weight."

The plaintiff in the case, Mark Janus, has worked for years as an Illinois state employee and pays about $550 annually to the powerful public-sector union known as AFSCME.

While not a member of the union, he is required under state law to hand over a weekly portion of his paycheck, which he says is a violation of his constitutional rights.

"The fundamental issue is my right to choice," said Janus outside the court, after attending the arguments. "I had to pay the fee. Nobody asked me. I wasn't given the opportunity to say yes, which is also, ultimately, the ability to say no. ... That's what [the] whole case is about."

Labor leaders oppose so-called "free riding" by workers like Janus, and say they have a legal duty to advocate for all employees.

"It definitely hurts the ability of unions to discharge all of their responsibilities, from administering contacts, to negotiating terms, to handling grievance procedures," said David Frederick, an attorney representing AFSCME, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. "It's an economic fact, if you have less money, and you have people that are free riding, then it's harder for you to do your job."

The high court is being asked to overturn its four-decade-old ruling allowing so-called "fair share" fees for public employees.

While the current case applies only to them, the repercussions could affect unions nationwide.

Union membership nationwide is less than 11 percent of the American workforce, but about a third of government employees are members.

The Supreme Court had deadlocked when the issue was revisited two years ago, just after Scalia died.

Gorsuch, the replacement named by President Trump, faced strong labor union opposition at his confirmation hearings last spring, but told senators his record backing workers was strong.

While Gorsuch seeks to keep court-watchers guessing, Trump's Justice Department has been clear on its position -- announcing in December it was reversing course from the previous administration and supporting Janus.

"I think people who are in public sector unions are very concerned about their viability going forward."

Such legal turnarounds are rare, but the union fees case is one of three this Supreme Court term where the Trump Justice Department is taking a new interpretation.

That prompted Justice Sonia Sotomayor to add rhetorically, "How many times this term already have you flipped positions from prior administrations?"

Frederick said some unions might respond to loss of power and money by becoming more "militant" in their relations with management, "in search of short-term gains that they can bring back to their members and say stick with us."

But Chief Justice John Roberts said just the opposite might occur.

"The argument on the other side, of course, is that the need to attract voluntary payments will make the unions more efficient, more effective, more attractive to a broader group of their employees. What's wrong with that?"

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wondered the extent a ruling against the public-sector unions could then be applied to bar fees on free speech grounds for a range of shared resources, such as student activity fees and bar association dues. And she posed the big question big labor worries most about.

"What about the private sector, agency fees compelled by state law in the private sector?" Ginsburg asked.

About 28 states have so-called "right-to-work laws" that prohibit or limit union security agreements between companies and workers' unions.

States that do allow "fair share" fees say they go to a variety of activities that benefit all workers, whether in the union or not. That includes collective bargaining for wage and benefit increases, grievance procedures, and workplace safety.

Employees who do not join a union also do not have to pay for a union's "political" activities, but both sides of the issue are at odds over when that would occur.

Court watchers say the legal and political stakes in the Janus case could well determine the future of the union movement.

"I think people who are in public sector unions are very concerned about their viability going forward. Certainly opponents of unions see this case as something that they hope will substantially diminish the power of labor," said Elizabeth Wydra, president of The Constitutional Accountability Center. "But make no mistake, this case is a very serious potential blow to the union movement."

The case also revealed a split within Illinois state politics. The state's Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and Democratic Attorney General Lisa Madigan are on opposite sides of the case. Some conservative groups backing Janus have said some of Rauner's public comments predicting victory against the unions were inappropriate and unhelpful to their side.

The governor did not file a supporting brief in favor of Janus, but Madigan's office did argue its case on behalf of the state, in front of the justices Monday.

The case is Janus v. AFSCME Council 31 and Madigan (16-1466). A ruling is expected by late June.