Ernst: Military has greatly declined over the past few years

Iowa senator hopes the president focuses on national security in his address to Congress

Washington has a spending problem. It also has an “explaining problem.”

In fact, the latter may be a bigger issue. The explaining problem” certainly helps illustrate last week’s Senate and House votes to prevent a government shutdown, suspend the debt ceiling and devote an immediate $15.25 billion for hurricane relief.

The Senate on Thursday approved the triplicate package 80-17.

All noes came from GOP senators, but not before a failed effort by Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., to offset the hurricane money with unspent foreign aid dollars. The Senate also neutered a plan by Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., to decouple the hurricane assistance from overall government funding and the debt-ceiling freeze.

It’s easy to characterize the bill as “emergency hurricane aid legislation” -- which it was. But in an impassioned speech shortly before the vote, Sasse described the bill as “much clunkier and much less explicable or defensible to your or my constituents.”

Congress long ago designed the debt ceiling as a tool to harness spending. In other words, if you want to spend more, then lawmakers should be on record as voting to lift the debt limit.

However, that principle became a problem when entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security exploded. Congress long ago authorized all of those entitlements, which consume two-thirds of all federal spending and drive up the debt.

Congress doesn’t vote at regular intervals to approve money for entitlements. Yet lawmakers must regularly cast ballots to increase the debt ceiling -- a threshold challenged by the growth of entitlement programs.

Those phenomena don’t jibe. So lawmakers sweat nearly every year about taking what the casual observer would interpret as a vote to “spend more.”

That makes lifting the debt ceiling one of the most virulent votes a lawmaker can cast. However, a failure to increase the debt ceiling could spark a stock market crash or trigger a downgrade in the government’s credit rating.

That’s why presidential administrations and congressional leaders of both parties always hunt around for some method to latch a debt ceiling increase with something else. This time, convenient alibis boiled in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Basin. So Congress had to approve emergency spending for hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

Of course, not everyone would vote yea on such an amalgamated legislative package. But more than enough would. That perversely eases the blow of lifting the debt limit by … wait for it … spending more money.

“We’re going to use the hurricane as an excuse to hide from the truth,” lectured Sasse on the Senate floor. “We're not going to have any conversation about the fact that we constantly spend more money than we have and we have to borrow to do it.”

The Senate then approved the package 80-17. Sasse and Paul were among the noes.

This is where the “explaining problem” comes in.

At the time, Irma was forecast to lash South Carolina with its torrents. Yet. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., voted nay.

“I’ve got zero problem helping people with hurricanes,” he said. “I’ve got a real problem of legislating in a fashion that continues to put the military in a box.”

Graham was referring to the interim spending part of the combo bill that funds the government through December 8. No quarter of the U.S. government bears a bigger hardship than the Pentagon when Congress only grants the services a few months of spending direction.

“This just puts us right back into the cauldron here, and we’re going to have another crisis in 90 days,” Graham said. “It was more of a protest vote than anything else.”

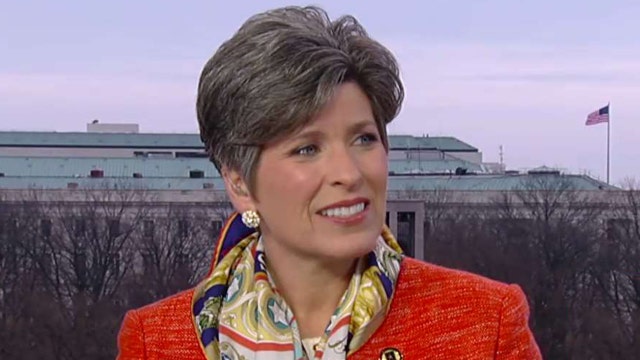

Or consider the approach taken by Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa.

“Ernst Supports Relief for Hurricane Harvey Victims, Votes No on Debt Limit Increase,” trumpeted a news release from her press shop.

Like Graham, Ernst voted no on the legislative trifecta. The jerry-rigged bill forced lawmakers who voted nay to concoct oratorical contortions to explain why they favored hurricane assistance yet opposed the debt ceiling.

Ernst argued she backed the Sasse plan for a standalone hurricane aid package, But note that she didn’t even say she voted “for” Sasse’s effort, only “supports.”

That’s because there was never a straight, up-or-down vote on Sasse’s effort. The Senate voted only to table, or kill, Sasse’s motion to limit the bill to hurricane funding.

So with no direct vote, Ernst is stuck. She’s left saying she “supports hurricane relief.” However, the Senate did take a full-on roll call vote on the underlying legislation that funded the government, addressed the hurricanes and iced the debt ceiling. Therefore, Ernst’s statement indicates she “votes no on debt limit increase.”

Voting no on the debt ceiling may sound great to fiscal conservatives. But others could flag Ernst’s vote against the hurricane money. Lawmakers and their wordsmiths convulse when forced to draft tortured statements to explain vote nuances.

And remember that most of the reason behind lifting the debt ceiling isn’t because of a vote Ernst or any other senator cast. It’s mostly because entitlement programs are dialed-in on automatic pilot. The money flies out the door without a congressional check.

This sums up the quintessence of Washington’s gnarled “explaining problem.”

On Friday morning, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney headed to Capitol Hill to appeal to House Republicans to support the plan.

Someone from Equifax could have made a better case for their cybersecurity protocols. Many Republicans found Mulvaney’s appearance particularly ironic. He formerly led the conservative House Freedom Caucus and repeatedly rejected debt limit hikes when he represented South Carolina in the House.

“We should have sold admission passes for the discussion. I heard it was a sight to behold to have Mick Mulvaney coming in arguing for a debt ceiling increase,” scoffed Rep. Charlie Dent, R-Pa.

Despite Mnuchin and Mulvaney’s entreaty, the House voted on the Senate-approved plan 316-90. All 90 noes came from Republicans. Only 133 Republicans voted yea -- compared to 183 Democrats. Lawmakers from both parties again stated their abhorrence to lump issues together. But the defense from those who voted yes was that they had to do this.

There is a remedy, however.

Congress could really curb the fiscal trajectory and neutralize debt ceiling crises if members adopted a “budget” that indeed tamed Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security spending.

A congressional “budget” is different from appropriations bills, which were contained in the “no government shutdown” part of this package. Same for emergency disaster relief money. Budgets address all federal spending – including entitlements. And they’re not binding.

But here’s the problem: The Budget Act of 1974 compels the president to draft a budget model and submit it to Congress. The House and Senate are supposed to approve their budgets in the spring. But as you can begin to imagine, neither has done so this year. Thus, the “explaining problem” raises its ugly head.

In the late winter and spring, Mulvaney crafted a budget “blueprint” for the Trump administration and specifically referred to it as such. Presidential budgets are aspirational. The numbers don’t have to add up and rarely do. Same for those written on Capitol Hill. For years, Republicans designed “budgets” that purportedly steer federal spending on a path to “balance” over a period of years. They look great on paper.

Lawmakers who fancy themselves as fiscal hawks get the chance to “explain” why this is such a good idea.

Yet federal spending climbs. Rendezvous with the debt ceiling continue. That’s because Congress rarely approves a concrete budget which actually implements true spending reforms. Congress passed the Budget Control Act after an epic tussle over the debt ceiling in August, 2011.

The BCA imposed serious fiscal restraints known as sequestration -- though none of the spending strictures touched entitlements. Lawmakers could adopt a budget that if fact curbs the fiscal trajectory. To be sure, it’s hard. But instead, lawmakers spend time “explaining” the virtues of this budget or that one. But bona fide reforms rarely happen.

For the most part, budgets without teeth are nothing but distractions. They entail a lot of explaining. Of course actually cutting entitlement programs would involve a lot of explaining to voters as well.

Think they have an “explaining problem” now?

With the current fiscal fight off the table, lawmakers will focus on tax reform. That sounds great. But lower taxes could mean higher deficits. One of the reasons the sides aren’t closer on tax reform is because it’s unclear if the math will work.

On its face, diminished federal revenue means higher deficits. Tax reform advocates assert federal coffers will be fine thanks to economic growth spurred by lower taxes.

Talk about a lot of explaining…

How about stumbling into a nuclear war on the Korean peninsula? You can forget about tax reform after that. That probably requires a hefty tax increase. And nuclear war doesn’t do a lot for deficit reduction either.

The catastrophes of Harvey and Irma will likely cost hundreds of billions of dollars of unexpected emergency spending. Last week’s $15.25 billion was just a down payment. We haven’t even discussed the price tag of flood insurance. The current federal program is $26 billion in the red.

House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, fretted at the flood insurance costs after hurricanes Katrina and Sandy.

“I warned at the time, if we do not fix the problem, we are one major storm away from having to bail it out again,” he said. “And here we are.”

Hensarling now worries about the flood insurance deficit after Harvey and Irma.

“We are incenting, encouraging and subsidizing people to live in harm’s way,” he said. “Shame on us if all we do is help rebuild the same homes, in the same fashion, in the same place.”

Yeah. But explain to home and business owners why they can’t rebuild where they were before.

“One day this is going to blow up on us. One day we will be judged by history,” Hensarling said.

He voted against Friday’s debt ceiling/government spending/hurricane bill. And some may ask if Hensarling and the other 89 GOP nays have some explaining to do.

“This should have been two separate votes,” Hensarling argued.

It’s all complicated. It’s tough to distill into 140 characters. The congressional appropriations and budget processes are monsters. The Treasury spends the money without major fiscal reforms. And that means Congress will tangle again with the debt ceiling again in a few months. Explain that.