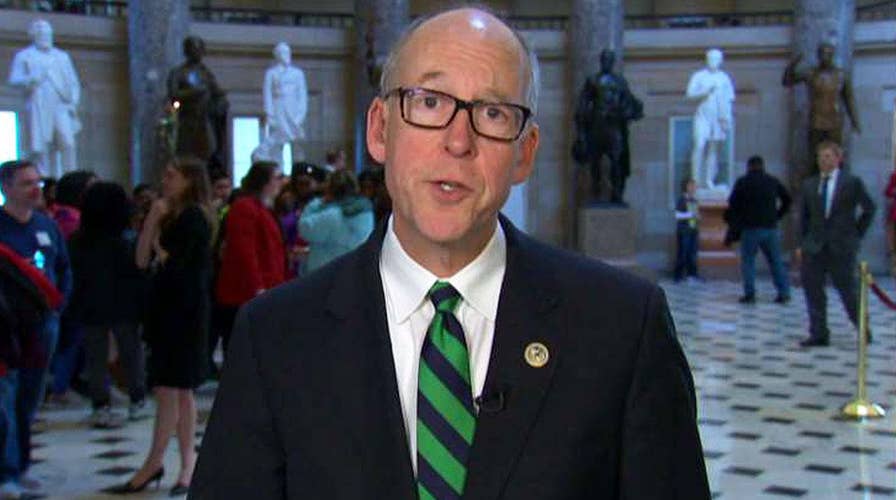

Rep. Walden's message for health care reform 'doomsdayers'

Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee weighs in on 'Happening Now'

In the auditorium of his old middle school just blocks from where he still lives, the congressman who is a lead author of the stalled House Republican health care bill was treated like the villain in a class play.

It didn't matter that Rep. Greg Walden was on a first-name basis with many of the roughly 800 attendees. Or that Democrats like Gov. Kate Brown call him congenial and bright. Or that Walden was just re-elected to a 10th House term with 72 percent of the vote in a safely Republican eastern Oregon district. Or that he is chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

Walden, 60, encountered the same angry buzz saw at town meetings last week that has greeted his Republican colleagues at similar sessions and prompted others to not even bother holding them. President Donald Trump and his party's policies on health care, immigration, the environment, the arts and Syria have whipped up Democratic voters and liberal organizers while dividing Republicans as well, and they're letting GOP lawmakers know it.

"Connie, I tried to answer you," Walden, standing alone on stage in a blue blazer and plaid shirt, pleaded to Connie Burton over resounding boos. Her children played with Walden's when they were little, but the 63-year-old Burton was now demanding that the lawmaker oppose Trump's voiding of rules blocking harmful emissions.

"Yes or no," the audience yelled when Walden answered indirectly.

Chosen to ask a question, one man in the balcony said, "You seem a like a pro-war politician. Have you encouraged your son to join the Marines?" A woman said, "We are absolutely disgusted that you led a committee to take away" peoples' health care, before loud cheers drowned her out.

"I care about health care. I know you don't think that," an exasperated Walden said at one point.

Walden's reception was far friendlier in more GOP-leaning Prineville, set among grazing land over 100 miles to the south. There were far fewer interruptions, though from the bleachers of the Crook County High School gym, 72-year-old Republican Steve Johnson yelled that Walden should "quit dancing around down there" and produce results in Congress.

But in Hood River, which despite its name is on the banks of the majestic Columbia River, and in Bend, the district's liberal hub at the foot of the Cascades, huge crowds pressed Walden in two-hour encounters heavy on boisterous interruptions and catcalls.

"People are fired up, and I know that and I respect that," Walden said in an interview. He said that as the sole Republican in Oregon's congressional delegation, "I am the place they can come and vent."

Congress is on a two-week recess that comes with Trump and the GOP health care bill faring dismally in polls, and Walden was often defensive about both. Republicans hope to resuscitate the health care measure and tackle budget, tax and infrastructure legislation, but public reaction — measured partly by town halls like these — will help determine their success.

The Republican measure would largely repeal former President Barack Obama's health care overhaul, including its tax penalties on people who don't buy coverage and expansion of Medicaid, which provides coverage for the poor. Walden stressed parts of that statute he would keep: its ban on lifetime coverage limits and a requirement that insurers cover even the most ill, costly consumers.

"We're going to protect people like you," he told Kim Schmith, 50, of Madras, who described her costly battle against breast cancer and said, "I am no longer uninsurable, and I want be insured."

Walden said Republicans want to improve competition at a time when insurers are fleeing many insurance markets. He said as the GOP tries reviving its bill, he believes its tax credits will be increased for poor people. Those proposed subsidies have drawn opposition from all sides as too skimpy for low earners.

Walden's role as a helmsman of the GOP drive to repeal Obama's law puts him in an odd political situation back home.

As a state legislator in the 1990s, he promoted health care innovations such as rating the cost and effectiveness of medical procedures that are credited with saving Oregon huge sums of money. Now in Congress, he represents a Democratic-run state that's embraced Obama's overhaul and adopted its expansion of Medicaid.

"The Republican health care proposal is a disservice to Oregonians and their access to health care," Brown, the governor, said in an interview. A one-time colleague of Walden in the Legislature, she said the GOP bill runs "counter to Oregon values." She predicted "political consequences" for Republicans.

Walden won all 20 of his district's counties last November and did better than Trump in all but one, so he may have little reason to worry. But clearly, there's a big constituency for Obama's law in Oregon.

Nearly one-fourth of Oregon's 4 million residents are on Medicaid, well above the national 20 percent average. That includes about 380,000 in the expanded Medicaid program Obama created to cover people earning modestly above the federal poverty level, an enlargement the GOP bill would phase out.

Walden notes that Oregon faces an $882 million Medicaid shortfall this year, partly because federal payments under Obama's statute are declining.

About 130,000 other Oregonians have bought policies on the online insurance exchange Obama established, with most getting federal subsidies. Overall, state figures show the proportion of uninsured Oregonians dropped from 17 percent before the law's full 2014 implementation to 5 percent now.

Walden's district, which encompasses over two-thirds of Oregon and is larger than 23 states, has taken full advantage of the law. With much of the district poorer than Oregon's coastal region, 240,000 of its residents receive Medicaid. In six of its 20 counties, more than 3 in 10 are beneficiaries.