Clarence Thomas absent from new African-American museum

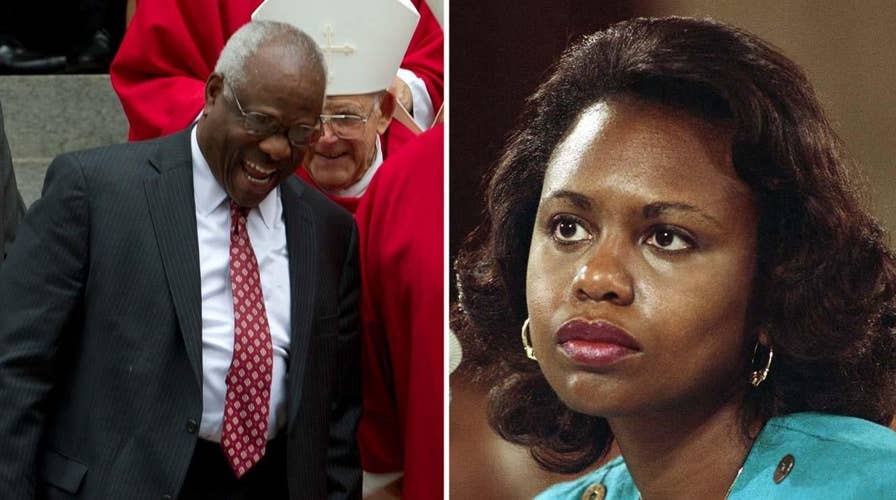

Sexual harassment accuser Anita Hill featured over Supreme Court justice

Justice Clarence Thomas marks his 25th anniversary on the Supreme Court this month, and befitting the man, it likely will be a low-key affair.

But while Thomas has broken barriers his entire professional life without seeking the limelight, the 68-year-old justice is being conspicuously ignored by a powerful new showplace for black heritage. The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened last month in Washington – and missing from the four floors of exhibits is any reference to Thomas' personal and judicial legacy, shocking for perhaps the second most powerful black political figure in America, after President Obama.

"Justice Thomas is the longest-serving black justice in our history, he's amassed over 500 opinions," said Mark Paoletta, a longtime friend who helped shepherd his nomination as a White House lawyer. "And yet you would learn nothing of that in this museum, and that's a shame."

What the museum does have is a prominent display of Anita Hill, who accused Thomas of creating a hostile work environment while her supervisor at a federal agency. She outlined her allegations during Thomas' 1991 confirmation hearings, and the candid discussion rocked the nation.

The museum panel has a picture of Hill speaking, with the caption, "Her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee provoked serious debates on sexual harassment, race loyalty, and gender roles."

Another section notes, "Outraged by Hill's treatment by the all-male Senate committee, women's groups organized campaigns to elect more women to public office." The exhibit also includes a pink button from the era: "I believe Anita Hill."

But it contains no pictures, quotes or memorabilia from the justice himself.

Thomas strongly denied Hill’s allegations and, a quarter-century ago Tuesday, told the senators and the nation what he thought of the personal political attacks on him.

"This is a circus. It's a national disgrace,” he said. “And from my standpoint, as a black American, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves ... and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you."

Smithsonian officials did not respond to specific requests for comment on the Thomas omission.

But Dr. Rex Ellis, associate director for Curatorial Affairs at the museum, told Fox News Chief Political Anchor Bret Baier last month that overall, curators tried to present a broad sweep of representation for a diverse, vibrant community.

"African Americans have been a part of the discussion of what the Constitution means, of what the Bill of Rights means and of what the laws that we have sort of made for our country mean as we go through time," Ellis said. "The Smithsonian has had a reputation for years of being a convener of bringing disparate groups and opinions and ideas together to talk about and to grapple with in ways that are beneficial."

Dahleen Glanton, a Chicago Tribune columnist, wrote, "Like it or not, Thomas is a historical icon. He deserves a prominent spot. If this acclaimed museum is to tell the true story of the African-American journey, it cannot sugarcoat the course."

Sources close to Thomas say the memories of his wrenching Senate confirmation in October 1991 are not forgotten by any means, but the experience, they say, has given him a greater appreciation of the unique role he now occupies.

Critics of the museum slight say it is especially glaring considering Thomas' own experiences with discrimination -- both before and during the modern civil rights movement.

The Georgia native was nominated to the high court by President George H.W. Bush to replace an icon -- Justice Thurgood Marshall. There were concerns raised by both Republicans and Democrats over whether Thomas would become the ideological opposite of the civil rights legend, since he had barely a year of judicial experience before being tapped for the Supreme Court.

Many people may not remember there were actually two Senate Judiciary Committee hearings for Thomas. The first session went pretty much to form, and with little judicial record to go on, lawmakers found little about which to criticize the nominee.

Then Hill stepped forward. She was a lawyer who had been hired by Thomas to work in the Education Department and later at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which he headed in the Reagan years.

She claimed Thomas made sexually suggestive comments on the job. In stunning nationally televised testimony, the poised Hill offered lurid details and called Thomas' alleged actions "behavior that is unbefitting an individual who will be a member of the court."

The allegations were never proven, and Thomas was confirmed by the Senate 52-48 -- the narrowest margin for a high court pick in a century.

For most Americans, Thomas slipped into virtual anonymity after he took his judicial oath. He shuns interviews and rarely speaks during arguments. In fact, he spoke up this year in a public case for the first time in years.

Behind the closed marble hallways of the court, Thomas is well known for his booming voice, hearty laugh and personable manner. Colleagues say they are amazed he seems to know every one of the several hundred employees by name, as well as their families.

"There are a lot of people who don't like the fact that he breaks their expectations," said Carrie Severino, chief counsel at the Judicial Crisis network and a former Thomas law clerk. "You know, he's his own man among conservatives."

This means Thomas often is a lone dissenter in cases big and small, ranging from state-federal authority to executive immunity to regulation.

His supporters say the Smithsonian snub is in some ways predictable, a reflection of the reality that many within the black community remain uncomfortable with his role on the bench.

"Clarence Thomas has his own views -- that's his sin. He believes in individual rights, not group rights. That's led him to oppose racial preferences, and for that he's banished" at the museum, said Paoletta, who also created the justicethomas.com tribute website.

Fox News’ Shannon Bream contributed to this report.