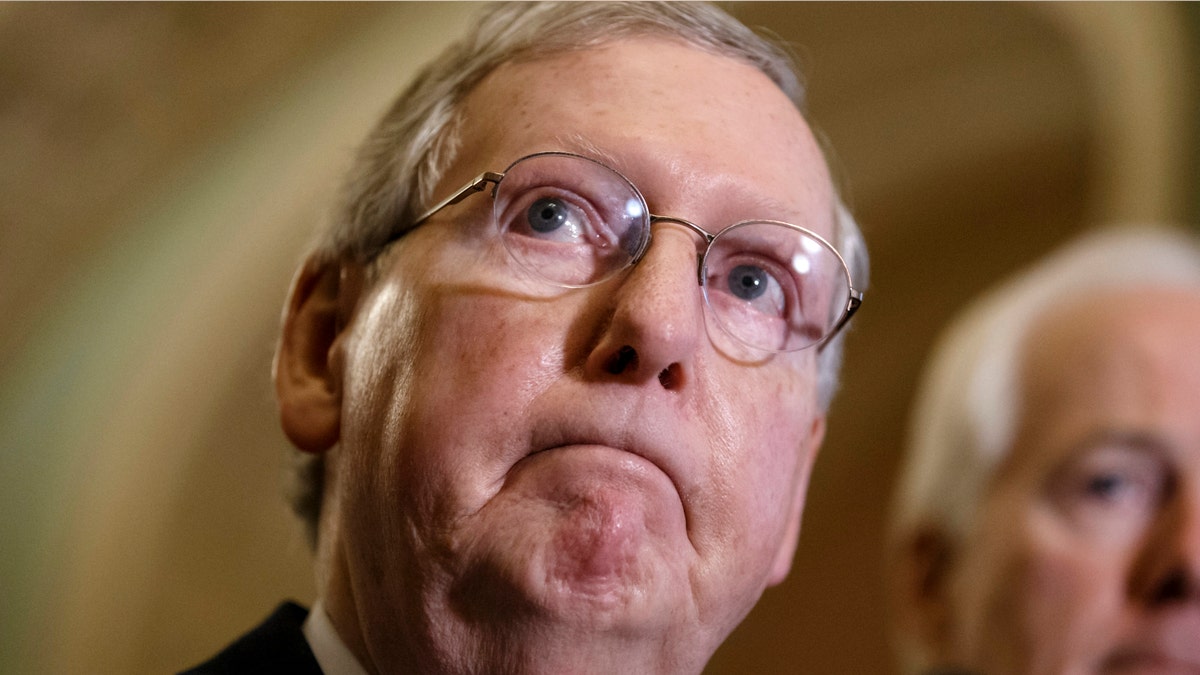

Dec. 2, 2014: Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Ky., accompanied by Senate Minority Whip John Cornyn of Texas, speaks with reporters following a closed-door policy meeting at the Capitol in Washington (AP)

WASHINGTON – Congress is poised to allow Americans with disabilities to open tax-sheltered bank accounts to pay for certain long-term expenses — the broadest legislation to help the disabled in a quarter-century.

The House was set to vote Wednesday on the bill, called the Achieving a Better Life Experience Act, which stands out in a bitterly divided Congress for its wide-ranging support. First introduced in 2006, the legislation now lists an overwhelming 85 percent of Congress as co-sponsors, even after a conservative group criticized it as "decisive step in expanding the welfare state."

In the Senate, where Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., are co-sponsors, the bill was expected to move quickly in the lame-duck session once the House acts. It would be the first time that Congress passed major legislation for the disabled since the 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act.

"This levels the playing field for people less fortunate than we are," said Rep. Ander Crenshaw, R-Fla., the bill's lead House sponsor. "And it demonstrates we can work together when it's something that affects so many people."

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, the House Republican Conference chairwoman, says her 7-year-old son, Cole, has Down syndrome, and that has made her committed to supporting the bill and other government policies that help people with disabilities achieve "the freedom to live independently."

Modeled after tax-free college savings accounts, the bill would affect as many as 54 million Americans born with disabilities, amending the federal tax code to allow states to establish the program. Families would be able to set up tax-free savings accounts at financial institutions to pay for expenses such as education, housing, transportation, job training and health care.

The accounts could accrue up to $100,000 without the person losing eligibility for government aid such as Social Security disability payments; currently, the asset limit is $2,000. Medicaid coverage would continue no matter how much money is deposited in the accounts.

The measure is aimed at helping people like Sara Wolff, 31, of Moscow, Pennsylvania, who has Down syndrome. A clerk at a law firm, she cannot work additional hours to save more without losing Social Security benefits and says the death of her mother this past year made her realize the importance of being able to plan for the future.

"Just because I have Down syndrome, that shouldn't hold me back from achieving my full potential in life," Wolff said.

Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pa., the lead sponsor in the Senate, said the measure will provide financial peace of mind to people with disabilities who "face daily struggles that we can't even begin to imagine."

The bill's path hasn't always been smooth. Some lawmakers hedged on cost until it was pared down to $2 billion over 10 years, reached in part by clarifying that individuals must be diagnosed with a disability by age 26 to qualify.

Many lawmakers insisted on cuts or revenue increases to offset the cost; the bill's sponsors found the savings in part by increasing the amount of levies on property for tax-delinquent Medicare providers and suppliers and technical adjustments to cap worker's compensation.

The conservative Heritage Foundation remains opposed, saying current asset limits on government welfare benefits are needed to ensure taxpayer aid goes to "those Americans who need them the most." It worries that expanding aid eligibility could lead to additional potential for Social Security fraud and abuse, especially when it comes to mental disabilities, which can be sometimes difficult to diagnose.

More than 100 coalition groups which support the bill disagree, saying ABLE accounts would allow families to save money that is earned on their own. The groups are optimistic after months of petition efforts, calls and personal appeals to lawmakers that families of disabled people will get the support they need.

"We made this our No. 1 priority and have 85 percent of Congress supporting this, which is pretty historic in this political environment," said Sara Hart Weir, interim president of the National Down Syndrome Society.