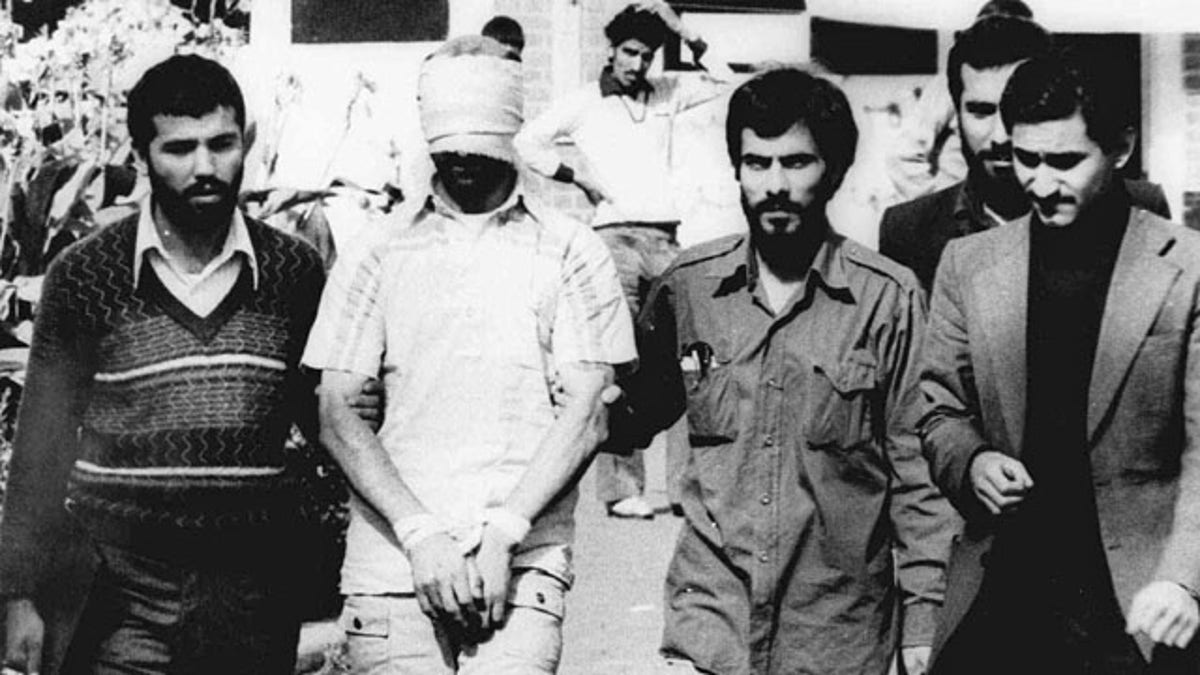

FILE - In this Nov. 9, 1979, file photo, one of the hostages being held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran is displayed to the crowd, blindfolded and with his hands bound, outside the embassy. (AP Photo)

McLEAN, Va. – A nuclear deal between the U.S., Iran and other world powers has been described a trust-building step after decades of animosity that hopefully will lead to a more comprehensive deal down the road.

But for many of the 66 Americans who were held hostage for 444 days at the start of the Iranian revolution, trusting the regime in Tehran feels like a mistake.

"It's kind of like Jimmy Carter all over again," said Clair Cortland Barnes, now retired and living in Leland, N.C., after a career at the CIA and elsewhere. He sees the negotiations now as no more effective than they were in 1979 and 1980, when he and others languished, facing mock executions and other torments. The hostage crisis began in November of 1979 when militants stormed the United States Embassy in Tehran and seized its occupants.

Retired Air Force Col. Thomas E. Schaefer, 83, called the deal "foolishness."

"My personal view is, I never found an Iranian leader I can trust," he said. "I don't think today it's any different from when I was there. None of them, I think, can be trusted. Why make an agreement with people you can't trust?"

Schaefer was a military attache in Iran who was among those held hostage. He now lives in Scottsdale, Ariz., with his wife of more than 60 years, Anita, who also takes a dim view of the agreement: "We are probably not very Christian-like when it comes to all this," she said.

The weekend agreement between Iran and six world powers -- the U.S., Britain, France, Russia, China and Germany -- is to temporarily halt parts of Tehran's disputed nuclear program and allow for more intrusive international monitoring of Iran's facilities. In exchange, Iran gains some modest relief from stiff economic sanctions and a pledge from Obama that no new penalties will be levied during the six months.

To be sure, the former hostages have varying views. Victor Tomseth, 72, a retired diplomat from Vienna, Va., sees the pact as a positive first step.

Tomseth, who was a political counselor at the embassy in Tehran in 1979, had written a diplomatic cable months before the hostage crisis warning about the difficulties of negotiation with the Iranians.

Still, he said in a phone interview Monday that it is possible to cut a mutually beneficial deal with them.

"The challenge is Iranian society and politics is so fragmented that it's difficult to reach a consensus," he said -- a problem that is also present in the U.S.

He said he considers the deal "in a category of an initial confidence measure."

John Limbert, 70, of Arlington, who was a political officer held hostage during the crisis and later became deputy assistant secretary of state for Iran in 2009 and 2010, also supports the deal. He said he does not view it in terms of whether Iran can be trusted, but whether the regime recognizes that a deal is in their own interest.

"I would say there is a consensus among the leadership, and the consensus is, `We like to stay in power. We like our palaces. ... We've seen the alternatives in Egypt and Tunisia," where established regimes have been toppled, Limbert said.

He said it's a mistake to be overly pessimistic about the prospects for a deal.

"If we and the Iranians could never agree, then Victor and I and all our colleagues would still be in Tehran," he said. "The problem has been that our reality has been for the last 34 years that anything the other side proposed, you could never accept because by definition it had to be bad for us, because otherwise why would they propose it?"

For other hostages, though, their experience has led them to the conclusion that attempting to negotiate and expecting Iran to live up to its end of the bargain is a losing proposition. Sgt. Rodney "Rocky" Sickmann, 56, of St. Louis, then a Marine sergeant, remembers clearly being told by his captors that their goal was to use the hostages to humiliate the American government, and he suspects this interim deal is in that vein.

"It just hurts. We negotiated for 444 days and not one time did they agree to anything ... and here they beg for us to negotiate and we do," he said. "It's hard to swallow. We negotiate with our enemies and stab our allies in the back. That doesn't seem good."

The deal may also have a direct effect on some of the hostages who have long fought to sue the Iranian government for damages. The new agreement calls for $4.2 billion in frozen Iranian assets to be released, which could make it more difficult to collect a judgment on any successful suit.

"And what do we get out of it?" asked Barnes. "A lie saying, `We're not going to make plutonium.' It's a win-win for them and it's a lose-lose for us."