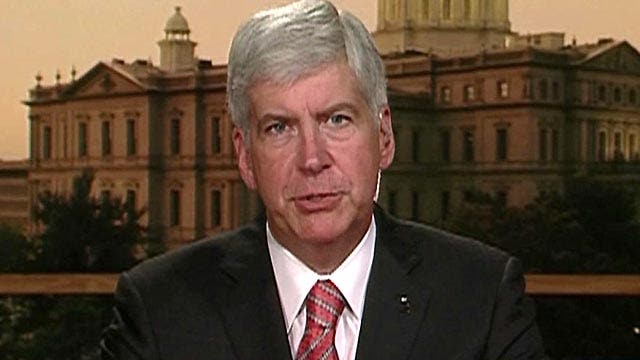

Gov. Snyder on Detroit bankruptcy: 'No other viable options'

Michigan governor on 'Special Report'

Detroit filed for the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history Thursday after steep population and tax base declines sent it tumbling toward insolvency.

The filing by a state-appointed emergency manager means that if the bankruptcy filing is approved, city assets could be liquidated to satisfy demands for payment.

Kevin Orr, a bankruptcy expert, was hired by the state in March to lead Detroit out of a fiscal free-fall, and made the filing Thursday in federal bankruptcy court.

"Only one feasible path offers a way out," Gov. Rick Snyder said in a letter to Orr and state Treasurer Andy Dillon approving the bankruptcy. The letter was attached to the bankruptcy filing.

"The citizens of Detroit need and deserve a clear road out of the cycle of ever-decreasing services," Snyder wrote. "The city's creditors, as well as its many dedicated public servants, deserve to know what promises the city can and will keep. The only way to do those things is to radically restructure the city and allow it to reinvent itself without the burden of impossible obligations."

Snyder had determined earlier this year that Detroit was in a financial emergency and without a plan to improve things. Snyder hired Orr in March, and he released a plan to restructure the city's debt and obligations that would leave many creditors with much less than they are owed.

Orr was unable to convince a host of creditors, including the city's union and pension boards, to take pennies on the dollar to help facilitate the city's massive financial restructuring.

Some creditors were asked to take about 10 cents on the dollar of what the city owed them. Underfunded pension claims would have received less than 10 cents on the dollar under that plan.

A team of financial experts put together by Orr said that proposal was Detroit's one shot to permanently fix its fiscal problems.

The filing leads to a 30 to 90 day period that will determine whether or not the city of Detroit is eligible for Chapter 9 protection, and define the number of claimants who may compete for Detroit’s limited settlement resources. The petition seeks protection from unions and creditors who are renegotiating $18.5 billion in debt and liabilities, according to the Detroit Free Press.

“The President and members of the President’s senior team continue to closely monitor the situation in Detroit,” White House spokeswoman Amy Brundage said in a statement Thursday.

“While leaders on the ground in Michigan and the city’s creditors understand that they must find a solution to Detroit’s serious financial challenge, we remain committed to continuing our strong partnership with Detroit as it works to recover and revitalize and maintain its status as one of America's great cities,” the statement read.

Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., remained positive about Detroit’s outlook in spite of the major blow that bankruptcy delivered:

“I know firsthand, because I live in Detroit, that our city is on the rebound in some key ways, and I know deep in my heart that the people of Detroit will face this latest challenge with the same determination that we have always shown,” the Senator said in a statement released Thursday.

In a press conference Thursday evening, Orr stated that bankruptcy is the "first step toward restoring the city," and promised that "nothing changes from the ordinary citizen's perspective."

In the same conference, Detroit Mayor Dave Bing said he didn't want the city to go bankrupt, but now that it's happened, the people of the city "have to make the best of it."

A number of factors -- most notably steep population and tax base falls -- have been blamed on Detroit's descent toward insolvency.

Detroit was once synonymous with U.S. manufacturing prowess. Its automotive giants switched production to planes, tanks and munitions during World War II, earning the city the nickname “Arsenal of Democracy.”

Detroit lost a quarter-million residents between 2000 and 2010. A population that in the 1950s reached 1.8 million is struggling to stay above 700,000. Much of the middle-class and scores of businesses also have fled Detroit, taking their tax dollars with them.

Detroit's budget deficit is believed to be more than $380 million. Orr has said long-term debt was more than $14 billion and could be between $17 billion and $20 billion.

Click for More at the Detroit Free Press

The Associated Press contributed to this report.