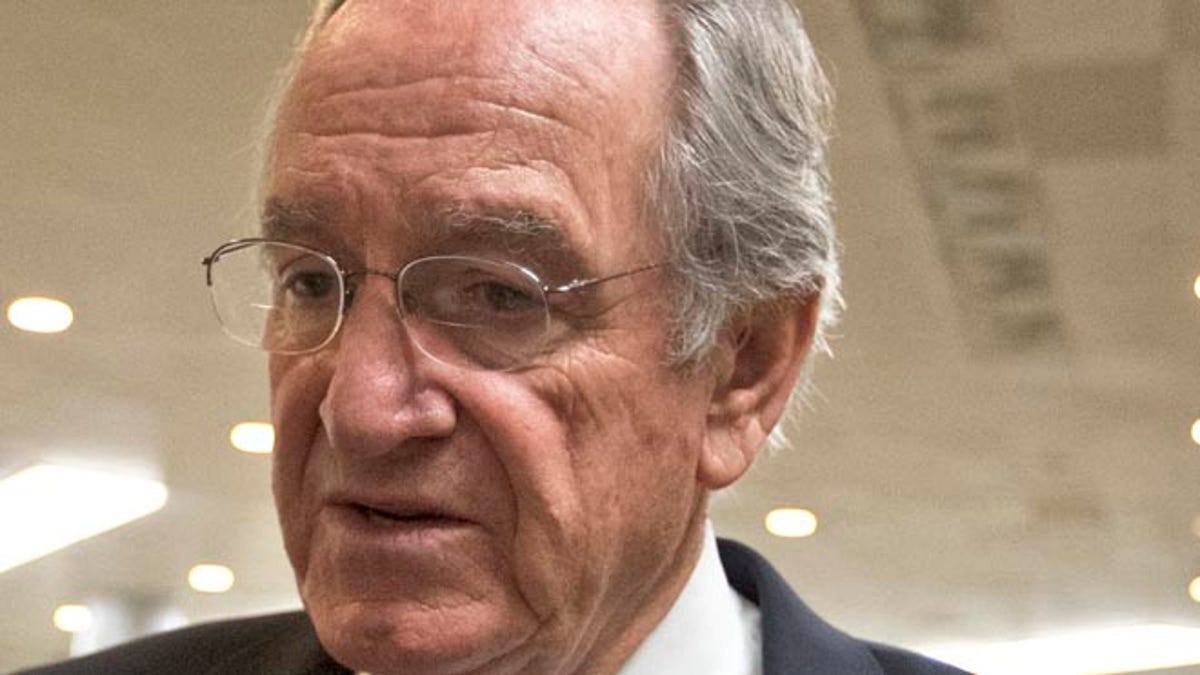

In this March 22, 2013 file photo, Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa speaks to reporters on Capitol Hill in Washington. Senate Democrats are introducing legislation that would replace the one-sized-fits-all national standards of No Child Left Behind with ones that states write for themselves. (AP)

WASHINGTON – The one-sized-fits-all national requirements of No Child Left Behind would give way to standards that states write for themselves under legislation Senate Democrats announced Tuesday.

The state-by-state approach to education standards is already largely in place in the 37 states that received waivers to the requirements in exchange for customized school improvement plans. The 1,150-page proposal from Senate education committee chairman Tom Harkin would require some of those states to tinker with their improvement plans and force the other remaining states to develop their own reform efforts. Education Secretary Arne Duncan would still have final say over those improvement plans, and schools would still have to measure students' achievements.

Buried on page 694 of the legislation, the proposal also includes protections for gay students. Schools that don't take stern measures against bullying or discrimination against gays or lesbians would see their federal funding cut. Democrats likened the measure to Title IX, which forced schools to provide equal opportunities for female athletes under threat of penalty.

The proposal faces an uphill climb.

A politically polarized Congress has failed to renew No Child Left Behind, also known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, since it expired in 2007. Harkin's Republican counterpart, Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, has supported updating No Child Left Behind but his approach has not always melded with Harkin's.

Those differences are likely to come into full view on June 11 when the education committee begins to fine tune the legislation. A vote by the full Democratic-controlled Senate has not been scheduled and Democratic aides suggested it could be autumn before one occurs.

Lawmakers in the Republican-led House, meanwhile, were reluctant to take steps that could be seen as telling local schools how to best teach their students and enrage tea party activists. Many GOP lawmakers also have been critical of Duncan's tenure as secretary and were unlikely to rush to give him more authority.

And a separate legislative wrangle over student loans is certain to get higher priority. Interest rates on new subsidized Stafford loans are set to double on July 1 without congressional action. Competing versions of legislation to dodge avoid that hike on students were making their way through the House and Senate.

The sweeping Elementary and Secondary Education Act governs all schools that receive federal dollars for poor, minority, disabled and students whose primary language is not English. The latest version of the law eliminates 20 programs while encouraging states to expand art, physical education and pre-kindergarten programs.

In exchange for those federal dollars, schools must meet standards -- previously set by Washington but increasingly dictated by state capitols.

The nation's largest teacher union, the National Education Association, applauded lawmakers for taking up changes to what it called a "flawed law" but urged them not to add importance to testing.

And the American Federation of Teachers chief Randi Weingarten called Harkin's bill "a good first step."

"The bill requires a variety of measures to evaluate teachers, rather than making test scores the be-all and end-all," she said.

But that does not mean schools would be off the hook for measuring students' achievements. Students would still be tested in reading and math each year from third to eighth grades, as well as once in high school. Schools would also have to measure students' aptitude in science at least three times between third grade and graduation.

But those tests could be combined with student portfolios or projects, an effort to win over the law's critics who said too much emphasis was placed on testing.

The proposal also requires schools to share detailed performance reports with parents.

Duncan has pushed Congress to update the law to accommodate challenges officials did not anticipate when the measure was passed on a bipartisan basis in 2001. But absent congressional action, Duncan has been giving states permission to ignore parts of the law that are unworkable in exchange for detailed school improvement plans.

Already, 37 states and the District of Columbia have been given such waivers. Alabama, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wyoming are still waiting to hear about their applications, along with a coalition of California districts.

In a memo circulating on Capitol Hill and among education advocates, Harkin's Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pension Committee acknowledges criticism of No Child Left Behind's requirements as "setting inflexible benchmarks without considering the different needs of schools and without recognizing student progress."

Instead, Harkin's bill would offer states greater flexibility to improve students' education.

The proposal "gets the federal government out of the business of micromanaging schools and instead enables states and districts to focus on turning around chronically struggling schools and those with significant achievement gaps," according to the committee's memo.