A lone gunman's deadly attack Wednesday at the Holocaust Museum in Washington shines new light on how the Internet has become a double-edged sword for law enforcement agencies trying to track domestic extremists and prevent hate speech from mutating into hate-fueled violence.

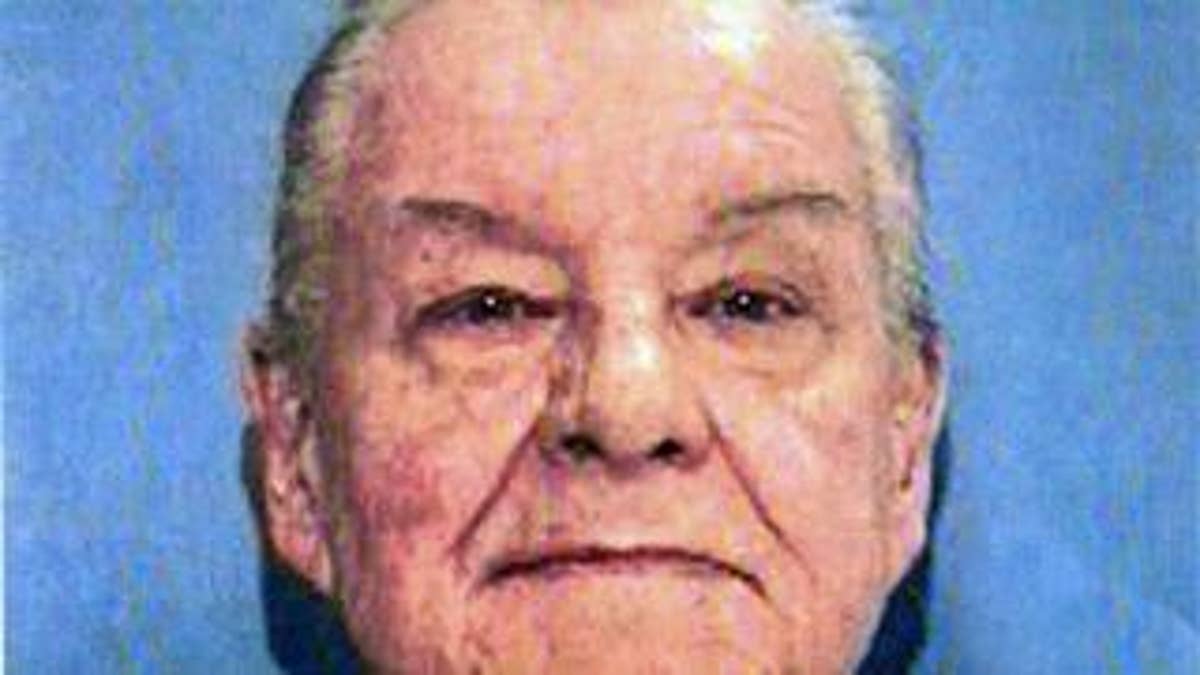

The suspect, James W. Von Brunn, accused of killing a guard in the shooting, is well known by watchdogs as a white supremacist with ties to hate-filled Web sites.

The Web has grown over the past decade as a forum for hate groups and twisted individuals whose views would leave them otherwise isolated. The number of active "hate sites" has risen from 366 in 2000 to 630 last year, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center's Intelligence Project. The number of active hate groups, meanwhile, rose from 602 in 2000 to 926 last year.

Although their online presence provides investigators with extensive, up-to-date information on hate groups' plans, protests and conspiracy rhetoric, the Internet also serves as an unmatched platform for empowering and connecting racists, anti-Semites and the like.

In addition, the Web sites, in some cases, are a taunt: They broadcast hateful rhetoric without crossing any legal lines, preventing law enforcement from being able to act on the warning signs.

"It's the greatest intelligence resource in the history of mankind. But on the other hand, it connects these people together in a way they used to not be able to. ... They've got people egging them on," said Heidi Beirich, research director at the Intelligence Project. She added, "The truth of the matter is just about anything you publish is going to have First Amendment protection."

Beirich, whose group studies such developments, said there actually are "thousands" of hate sites when you count those that haven't been updated in a while. And they have an effect on the mindset of readers who are already sympathetic.

Von Brunn, who was charged Thursday with first-degree murder, operated one of these sites, according to the charging document. The site, Holywesternempire.org, has since been taken down, but not before reporters got a glimpse of its extremist rhetoric. The site advertised a book Von Brunn had written, describing it as a "hard-hitting expose of the JEW CONSPIRACY to destroy the White gene-pool."

The site discussed what "you must do to protect your White family" from this threat.

"The stuff on there is so nasty, it's so guttural, and it could easily influence other people," Beirich said.

It's unclear how much Von Brunn was influenced by others via the Web, but he reportedly lived between 2004 and 2005 in Hayden, Idaho, which for years was home to the Aryan Nations, a neo-Nazi group.

Though law enforcement officials said Von Brunn was most likely a "lone wolf" type, or a conspiracy of one, they also worried there may be others like him.

And they publicly discussed the complications in pinpointing these people -- those who are at the breaking point, when their loaded speech and writings turn into action.

"Law enforcement's challenge every day is to balance the civil liberties of the United States citizen against the need to investigate activities that might lead to criminal conduct," Joseph Persichini Jr., with the FBI's Washington field office, said at a press conference Thursday. "No matter how offensive to some, we are keenly aware that expressing views is not a crime, and that protections afforded under the Constitution cannot be compromised."

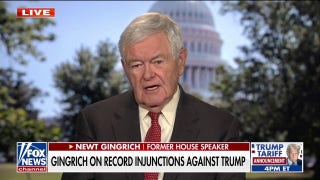

Case in point, Persichini said that the FBI did not have an open investigation on Von Brunn but was "aware" of him and his Web site.

"He is known as an anti-Semite and a white supremacist who had ... established Web sites that espoused hatred against African Americans, Jewish and others," he said.

In a signal that law enforcement needs public help in flagging such individuals, or copycats, Persichini made an urgent plea Thursday for people to contact the FBI with information about Von Brunn.

Two FBI officials, who spoke with FOXNews.com on condition on anonymity, said law enforcement have to handle suspect individuals on a "case-by-case basis," and although the Internet provides useful information, they are limited to investigating criminal activity -- in other words, a specific threat to kill or harm someone.

Occasionally, it rises to that level. A right-wing blogger in New Jersey, for instance, was charged this week for encouraging his readers to harm two Connecticut lawmakers.

But law enforcement agencies are pummeled with leads to sift through. One official said the FBI unit that handles complaints about Internet content -- be it hate speech or child porn -- receives between 800 and 1,000 complaints a day.

"Just a scant 15 years ago, these people were isolated by their community," one official said. "With the Internet now, that is global. A guy sitting in Virginia can be conversing with a guy sitting in California ... or around the globe."

The official said the Web provides "more possibilities" for people to "become more radicalized" by easily connecting with others who think like them.

Von Brunn was more than just a Web dweller. He apparently was active in white supremacist circles and associated with other Holocaust deniers.

But a string of recent incidents demonstrates the danger of the "lone wolf" types that the government has raised flags about -- the kind of individual motivated by narrow interests to commit violent acts, sometimes fueled by the chorus of a digital age.

Scott Roeder, the man charged with killing abortion doctor George Tiller late last month, reportedly had a history of posting anti-abortion comments on anti-abortion Web sites and told the Associated Press on Sunday that "many other similar events" are planned across the country as long as abortion stays legal.

The Tiller killing practically coincided with the killing of a soldier outside an Arkansas recruiting center.

Activists and analysts have suggestions for how to prevent such violence without breaching First Amendment freedoms. Fight speech with speech, Beirich says. In other words, overwhelm hate speech with endorsements of tolerance and condemnation of racist attitudes.

Dan Levitas, author of "The Terrorist Next Door," said the Holocaust Museum shooting points to the "great difficulty of intercepting it ahead of time" and underscores the need to proactively fight racist attitudes.

"I don't think it's possible to place every person who has a neo-Nazi Web site under government surveillance. As concerned as I am about the violent activities of racists and white supremacists ... we don't want government surveillance of anyone simply expressing a hateful idea," he told FOX News. "This should really be a wake-up call and an awareness to our civil society about the task that we have ... to still make sure that those ideas are not popular and are not encouraged."

FOX News' Catherine Herridge contributed to this report.