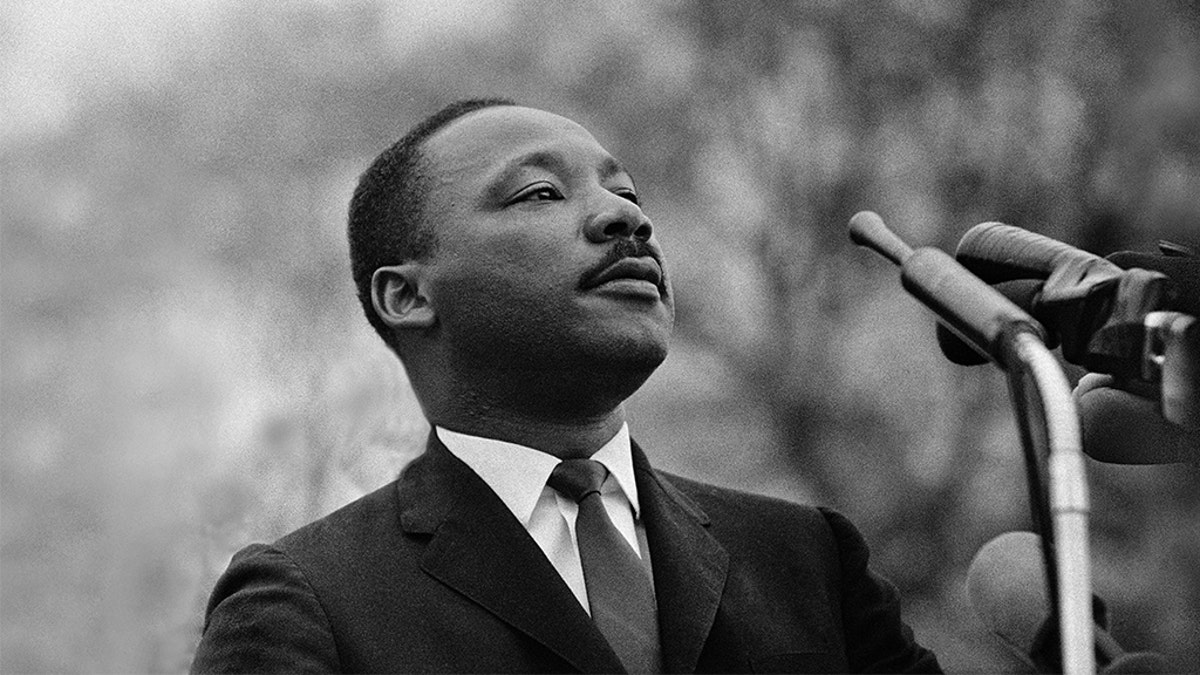

FILE-- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking before crowd of 25,000 Selma To Montgomery, Alabama civil rights marchers, in front of Montgomery, Alabama state capital building. On March 25, 1965 in Montgomery, Alabama. (Photo by Stephen F. Somerstein/Getty Images)

The nation will pause on Monday to recognize the birthday and legacy of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the civil rights leader who was gunned down on a Memphis motel balcony in April of 1968.

Born 90 years ago this past Tuesday in Atlanta, Georgia, the minister-turned-activist famously advanced racial equality throughout the 1950s and 1960s by championing tactics that centered on nonviolence and civil disobedience. Renowned for his soaring oratory and principled and passionate public addresses, Dr. King’s influence is still felt more than a half a century since his tragic death.

Legends tend to grow larger with the passage of time, as distance adds depth and historical perspective provides a certain heft to a person’s record and reach.

MARTIN LUTHER KING’S WISDOM, WORDS AND COMPASSION ARE NEEDED NOW MORE THAN EVER

But if the man who becomes a monument is magnified as the years roll on, then the mentors who educated and shaped those legends are often minimized, unintentionally but inevitably lost to public memory.

Granted, this has always been the case. We’re all familiar with the greatness of America’s first president and Revolutionary War general George Washington. Yet few of us would rightly credit William Fairfax, a Virginian who served as Washington’s surrogate father, with preparing the young man to found and lead a fledgling nation.

The men behind the monument that represents the life and legacy of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., are no different.

Enrolling in Morehouse College at the age of 15 in 1944 with a desire to become either a lawyer or a physician, the young Georgian encountered two men who literally changed the course of his life and, in turn, the trajectory of race relations in America.

As a young student at Morehouse College, King attended Tuesday morning chapels each week inside Sale Hall on the famed Atlanta campus. Presiding and preaching was Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, the school’s president. His sermons were dynamic, challenging students to not only excel academically but more importantly, consider how their individual gifts complemented God’s call on their lives.

Intrigued by Mays’ sermons, King would remain behind each Tuesday to talk with the president, peppering him with follow-up questions. The young student invited Mays home to dinner to meet his parents and a fast friendship was formed.

At the same time, a young Dr. King also encountered Dr. George Kelsey, Morehouse College’s Director of the School of Religion. Sitting in his classroom, the youngster was awed by the power and depth of Kelsey’s Bible teaching.

For a teenage Martin Luther King, Jr., the combination of Mays’ soaring oratory with Kelsey’s substantive lectures on race and faith convinced him that preaching could be both “mentally stimulating and emotionally satisfying.” Spiritually moved, King abandoned his original career plans and instead committed to the ministry, enrolling in seminary following graduation in 1948.

According to the late civil rights leader himself, absent the influence of Mays and Kelsey, he never would have dedicated his life to working towards a day when people would “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Like Mays and Kelsey for King, there are quiet but forceful mentors in almost every life, with many of them often fading from the forefront of our memories, sometimes only thought about when we dust off a yearbook, look thru an old file drawer or flip thru a tattered and frail family album. And while very few of us will ever ascend to the heights of Dr. King’s renown or be called upon to champion a cause as sweeping as the eradication of a nation’s racism, it would be impossible to overstate the impact of these seemingly anonymous influencers on our own lives.

All of us have been significantly shaped by people that most outside our intimate circle will soon forget and that the rolls of history will likely never record.

In my own life, I’m reminded of all the pastors, teachers, neighbors and coaches who patiently shepherded me through awkward adolescence and my anxious early adulthood. None of them are etched in marble but all of them left their mark on me in ways big and small.

In my early childhood of the late 1970s, I was oblivious to the racial tensions simmering around our white neighborhood on the South Shore of Long Island. But then came a knock at the door one summer night, and my father welcomed in a man from just down the street. As I recall, he had a grave look on his face and informed my father that a black family was planning to purchase an adjacent house. Holding out a clipboard, he wanted my dad to sign a petition objecting to the transaction. I’ll never forget my father’s response.

“I won’t do it,” he said, his voice breaking and his head shaking. “That’s not right.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Forty years later, I remember nothing else about that warm evening, but I’ll never forget the profound lesson about racial equality that my father taught me in his short but pointed seven-word response.

It was the poet John Donne who famously wrote that, “No man is an island, entire of itself,” but rather “every man is part of the continent, a part of the main.” And so it goes with a legend as large and consequential as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He was a man of many gifts and many talents, but he was not self-made – nor are we. You and I are in significant ways the product of the lives that have touched ours – and let’s never forget that our lives are also regularly touching others, too.