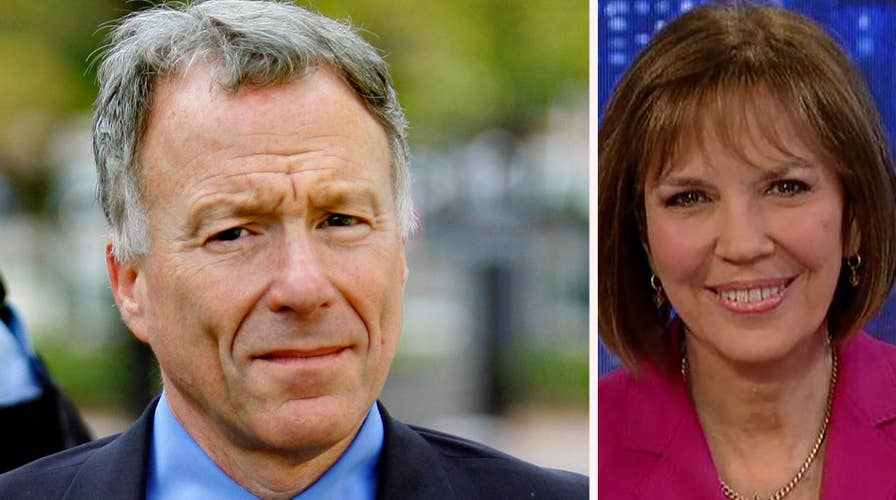

Judith Miller 'very delighted' by Scooter Libby's pardon

Judith Miller spent 85 days in jail for refusing to reveal Scooter Libby as her source; she shares her reaction on 'The Story' after Trump pardons Libby.

Justice deferred may be justice denied. But for I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby – former Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, who was convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice in 2007 – President Trump’s pardon on Friday, however belated, was welcome. For me, too.

Thirteen years ago, as a New York Times reporter, I went to jail to protect the identity of my news sources, and one source in particular – “Scooter” Libby.

In 2007 I had testified against Libby, saying that I thought he and I had discussed Valerie Plame, a CIA agent whose identity he was said to have leaked to the media to punish her husband for challenging intelligence about weapons of mass destruction that President George W. Bush had cited to justify the 2003 war in Iraq.

Critics of the war were outraged and demanded an independent investigation of the leak by a special prosecutor. While Libby was never charged with leaking Plame's name, he was convicted of lying to the FBI and a grand jury and of obstructing justice in the leak investigation.

At a news conference after Libby's conviction, Patrick Fitzgerald – the special prosecutor appointed by then-Deputy Attorney General James Comey (who later became FBI director) – called my testimony crucial to the verdict.

So why would I be pleased with Libby's pardon? Because after leaving jail and investigating the case, I unearthed information that convinced me not only that my testimony was in error, but that Libby was the victim of an overzealous prosecutor whose investigation should have ended before it began.

I described my findings in a 2015 memoir about high-stakes journalism, “The Story, A Reporter’s Journey.”

The first thing I learned was that John Rizzo, the CIA’s former general counsel and an agency lawyer for over 30 years, disputed prosecutor Fitzgerald’s assertion that Valerie Plame had been a super-secret covert agent who was not well known outside of the intelligence community and that the leak of her name had caused grave, if unspecified, harm to America’s national security.

Rizzo told me in an interview and subsequently wrote in his own book that “dozens, if not hundreds of people in Washington” knew that Plame worked for the CIA. Even more significantly, he said, a CIA damage assessment of the leak had produced “no evidence” that her outing had harmed any CIA operation, any agent in the field, or “anyone else, including Plame herself.”

I also learned that the CIA assessment had been finished in late 2003 or early 2004, long before Libby was indicted or I went to jail. Although prosecutor Fitzgerald knew this, Rizzo's crucial CIA finding became public only after his book was published. But if the leak had caused no national security harm, why had Fitzgerald continued the inquiry?

Fitzgerald refused to discuss the case with me after the trial. Nor would he say why he pursued Libby after learning early in the inquiry that the source of the leak was not Libby, but Richard Armitage, an aide to Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had argued against the war. But Armitage was never punished for releasing classified information.

Then I learned that Fitzgerald had withheld exculpatory evidence not only from me but also from Libby's lawyer that might surely have jogged my memory and prevented me from unwittingly giving false testimony against him. Finally, the prosecutor opposed letting the jury hear information about how often memories of such conversations fail.

I hoped that President Bush might pardon Libby. But while he commuted Libby’s sentence of 30 months in jail, he refused to issue a full pardon despite repeated pleas from Vice President Cheney, who argued that Libby was a de facto scapegoat for public fury over and opposition to the war.

In retrospect, it is clear that Libby’s prosecution marked the beginning of the criminalization of policy differences – a dangerous trend that continues to this day. In light of all this, I'm pleased that Libby has finally been pardoned.

The ink on the pardon was barely dry, however, when critics began saying that President Trump pardoned Libby to signal those facing charges in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe that he will pardon them as well if they are convicted. The pardon was intended to persuade those facing the special prosecutor’s scrutiny not to cooperate or to lie, they said.

Since I never discussed a pardon for Libby with any White House official, I have no idea what motivated President Trump’s decision. In its announcement, the White House said that my book’s recantation of my testimony had helped persuade the president that Libby had been treated unfairly.

But Fitzgerald's and Robert Mueller's probes are not the same. The targeting of Libby was baseless, since the prosecutor knew early on that no crime had been committed and that Libby was not the source of the initial leak of Plame's name.

Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, by contrast, was real, whether or not it succeeded, and efforts to determine whether President Trump or senior members of his campaign conspired with the Russians to enable such meddling clearly warrant an independent probe.

The Libby investigation was not prompted by a national security threat, whereas Russian meddling in a presidential election was an attempted assault on a pillar of American democracy. It must not be ignored.

And efforts to understand the depth and scope of Russian disinformation campaign cannot be dismissed as a "witch hunt." Any tweeted signal to obstruct it imperils not only the investigation, but democracy itself.