The NFL players kneeling during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in football stadiums across the country are engaging in protests based on false claims and misleading media reports that give the impression that police are killing African-Americans at a rate greater than they are killing whites.

In addition, my own research shows that contrary to some claims, blacks have good relations with police they deal with in their neighborhoods.

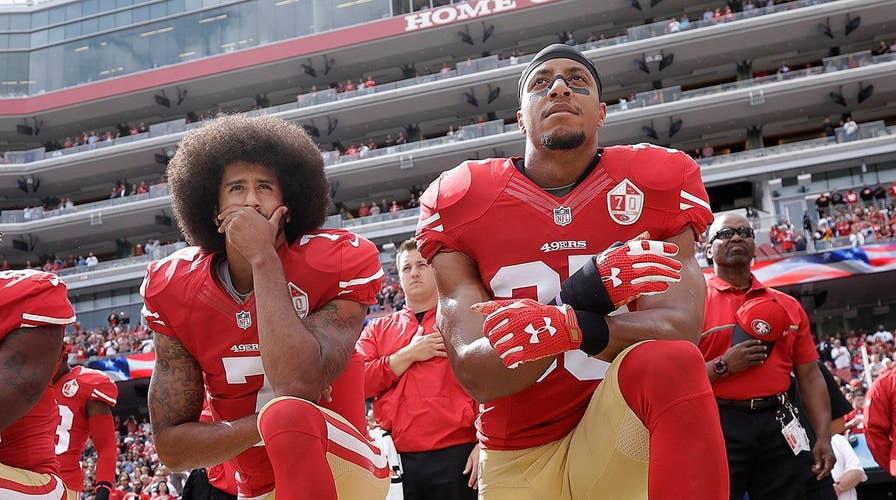

After Colin Kaepernick, then a quarterback with the San Francisco 49ers, started kneeling during the playing of the national anthem 13 months ago, he said: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color…. There are bodies in the street and people (police) are getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

However, a study last year by Harvard Economics Professor Roland Fryer, who is black, concluded that for the Houston police department: “On the most extreme use of force – officer-involved shootings – we find no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are taken into account.” Unfortunately, he doesn’t have the race of the officer doing the shooting and the data for just one police department doesn’t allow the investigation of police policies.

Using four national databases of crime statistics representing confrontations between police and civilians in many parts of the U.S., the study did find that blacks were more likely than whites to be treated with some lower level of force by police during confrontations – such as being handcuffed, pushed to the ground or pepper-sprayed. That is a legitimate issue that merits further study. But it’s not the same as saying racist white cops are – to use Kaepernick’s inflammatory phrase – “getting away with murder” of African-Americans.

A July poll in New York City found that blacks strongly support the cops in their own neighborhoods – 62 percent approve compared to just 35 percent who disapprove. That rating is 11 percent higher than blacks give the New York City Police Department as a whole.

Last Sunday, Hillary Clinton joined the debate, saying the player protests that have spread across the league “demonstrate in a peaceful way against racism and injustice in our criminal system.” She added that President Trump’s tweets denouncing players who kneeled during the anthem were “very clear dog-whistles” to his base, implying an appeal to anti-black racism.

The media have helped create a biased perception that is far from reality on police shootings. In a new study, the Crime Prevention Research Center (where I serve as president) finds that when a white officer kills a suspect, the media usually mention the race of the officer. This is rarely true when the officer is black.

As a result, many people incorrectly believe the police are racist. But when it comes to the cops who African-Americans deal with personally, they often have a different view.

For example, a July Quinnipiac University poll in New York City found that blacks strongly support the cops in their own neighborhoods – 62 percent approve compared to just 35 percent who disapprove. That rating is 11 percent higher than blacks give the New York City Police Department as a whole, where perceptions are far more likely to be influenced by media reports.

Data also show that blacks don’t hesitate to reach out to police and report crime. Indeed, from 2008 to 2012, blacks were actually more likely than whites, Hispanics or Asians to report violent crimes committed against them to the police.

How do we know this?

The Department of Justice conducts an annual survey that asks people if they have been the victim of a crime. That’s how we know how much crime there is in each neighborhood. Then, the Crime Prevention Research Center study compares that crime rate with how often people actually reported crimes to the police.

What we find is that blacks were 9 percentage points more likely than whites (54 percent to 45 percent) to report a crime to the police. Blacks are 16 percent more likely than Hispanics and 12 percent more likely than Asians to report a crime.

It's not just that blacks report more crime because they experience more of it. This higher rate of reporting even holds true in areas where other groups face higher violent crime rates than blacks do.

More importantly, this trust in local community police appears to be well-placed. This is because despite what Kaepernick and others falsely claim, white police officers aren’t killing defenseless blacks just because they can. Blacks also are a smaller percentage of people killed by police than the black share of murderers and other violent criminals.

Through extensive research, we found 2,699 police shootings across the nation from 2013-2015. That’s far more than the FBI found – its data is limited to only 1,366 cases voluntarily provided by police departments.

The FBI data has other problems, too: It disproportionately includes cases from heavily minority areas, giving a misleading picture of the frequency at which blacks are shot.

Our database also keeps track of characteristics of both the involved suspect and the officer in each shooting, local violent crime rates, demographics of the city and police department, and many other factors that help determine what causes police shootings.

Here’s what we found:

Black officers were at least as likely as their white peers to kill black suspects.

When more police are present at the scene of a confrontation with a civilian, suspects face reduced odds of being killed. The difference is about a 14 to 18 percent drop in the chances of being killed for each additional officer. Officers feel more vulnerable if they are alone at the scene, making them more likely to resort to deadly force. By the same token, suspects can be emboldened and resist arrest when fewer officers are present.

Police unionization has a harmful effect. Despite the success of the unionized NYPD, which has a good track record on shootings, our study finds that in general, police unionization has had the largest harmful effect, making suspects at least 65 percent more likely to be killed. This could be due to the fact that unions shield their officers from scrutiny with rules that delay prosecutors questioning officers. This may make officers more willing to shoot when their own safety feels at all jeopardized.

Body cameras don’t make a difference. Many people support having officers wear body cameras. But we surveyed 900 police departments, 162 of which reported their officers used body cameras. We found that police did not change their behavior when they started wearing the cameras.

It is a dangerous fiction that prejudiced white officers are going out and disproportionately killing black men. But that doesn’t mean that measures can’t be taken to reduce police shootings. The most obvious step would be to increase the number of officers, in the hopes that more will be present at the scenes of these incidents.