(AP)

We know that young people have the power to swing elections. 49 million young people, ages 18-29, are eligible to vote, compared to roughly 45 million seniors who are eligible. In 2012, if young people had split their votes equally in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Florida, instead of overwhelmingly supporting President Obama, Governor Mitt Romney would have won those states and would be president today.

Since 1972, every Republican candidate had to win the youth vote in order to win the presidency, with one exception: George W. Bush won in both 2000 and 2004 despite the fact that young voters supported his opponents Al Gore and John Kerry, respectively.

In his victory speech in Nevada last month, Donald J. Trump said, “We won with young. We won with old.” But the fact is, Mr. Trump did not win with voters under 30 in Nevada. He garnered 31 percent of young voters there, trailing Senator Marco Rubio’s 37 percent. That result reflects a wider trend so far in 2016: no Republican candidate, including the frontrunner, has managed to consistently capture the youth vote.

In the early state contests, young Republican voters supported Senator Ted Cruz in Iowa and South Carolina, Mr. Trump in New Hampshire, and Senator Marco Rubio in Nevada.

On Super Tuesday, the story was similarly mixed. In three states—Arkansas, Texas (where Senator Cruz won), and Virginia—young voters supported candidates other than Mr. Trump. In Alabama and Georgia, youth did support Mr. Trump, but by the smallest margin of any age group. Young people supported Trump at about the same level as the overall electorate in only two Super Tuesday primaries (Arkansas and Tennessee).

On March 5, young people divided their support fairly evenly across different candidates in Michigan, where Mr. Trump got 31 percent of young votes, Governor John Kasich 29 percent, and Senator Ted Cruz 25 percent. Mississippi, however, was a different story, as Trump received an estimated 45 percent of young votes. This outcome, combined with earlier results, may suggest that in the Southern states young Republican voters are starting to coalesce around Mr. Trump.

At the same time, youth participation in Republican contests has been historically high. And this is an emerging story of 2016: young Republicans continue to turn out in historic numbers, but have been slower to unite behind any one candidate, including the frontrunner.

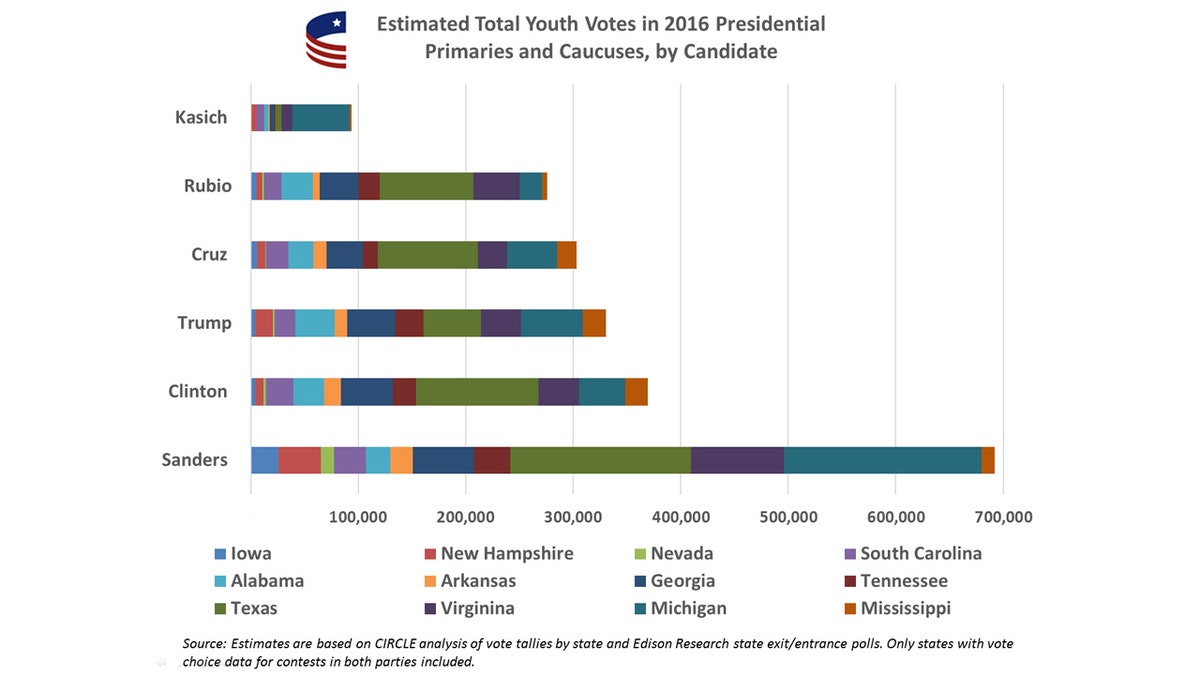

A similar, more widely reported narrative is playing out on the Democratic side: Secretary Hillary Clinton garnered an average of only 15 percent of young voters in the first three Democratic contests. And despite her campaign’s increased effort, youth, by and large, continue to support Senator Sanders.

On Super Tuesday, an aggregate total of 62 percent of young Democratic primary voters supported Senator Sanders compared to 37 percent for Secretary Clinton. However, the youth support for Senator Sanders ranged from more than 80 percent in Vermont and Oklahoma, to 54 percent in Georgia, to only 40 percent in Alabama. Secretary Clinton won 61 percent of the total Black youth vote but lost the Latino youth vote on Super Tuesday.

On March 5, in Michigan, young Democratic primary voters (ages 18-29) showed overwhelming support for Senator Sanders: 81 percent to 19 percent, giving him the votes to propel him to victory. In Mississippi, Secretary Clinton won young voters 62 percent to 37 percent, which was significant but tighter than the overall margin of her victory.

In recent years, even as young people have become increasingly politically engaged in other ways, they have voiced a growing distrust in voting and political parties. Now, with strong support for Senator Sanders, they may be declaring their intention to fundamentally shift the way our democracy operates. Meanwhile, on the Republican side, they may not be coalescing around Mr. Trump, certainly not as quickly as older voters are.

This year, if either party nominates a candidate who has been unable to unify the support of young voters, he or she will face the difficult task of engaging and inspiring youth in time to win the White House in November.

It is certainly not an insurmountable challenge, but it is an urgent one. If neither party succeeds at that task, we risk continuing the downward trend in voting by young people. That is worrisome, not just for our next president, but for the future of our country.

For the Republican Party, the situation could be even more acutely dire, as there are signs of generational gaps on key issues. Surveys consistently find young Republicans are more socially progressive than older Republicans. In addition, our analysis of Pew Research’s 2014 data indicates that 63 percent of young Republicans believe that “immigrants strengthen our country with their hard work and talents,” while 54 percent of older Republicans instead believe that “immigrants are burden” because they take jobs and resources.

Historically, young voters have generally chosen presidential candidates whose positions on major issues reflect their own, whether Ronald Reagan in 1984 or Barack Obama in 2008.

Right now, young Republicans have been slower to embrace Mr. Trump, and yet young Republican voters have not rallied around one of his opponents the way young Democrats are supporting Senator Sanders.

For years, young people have been a largely dormant political force, unengaged by candidates and parties who often ignored them or took their vote for granted. With high turnout in the primary season so far – particularly among young Republicans – and a lack of enthusiasm for both parties’ frontrunners, America’s youth may be sending a message that they’re done waiting, that they stand ready to assert their influence and shape the future of our democracy.

Both parties should get serious about listening.