(AP)

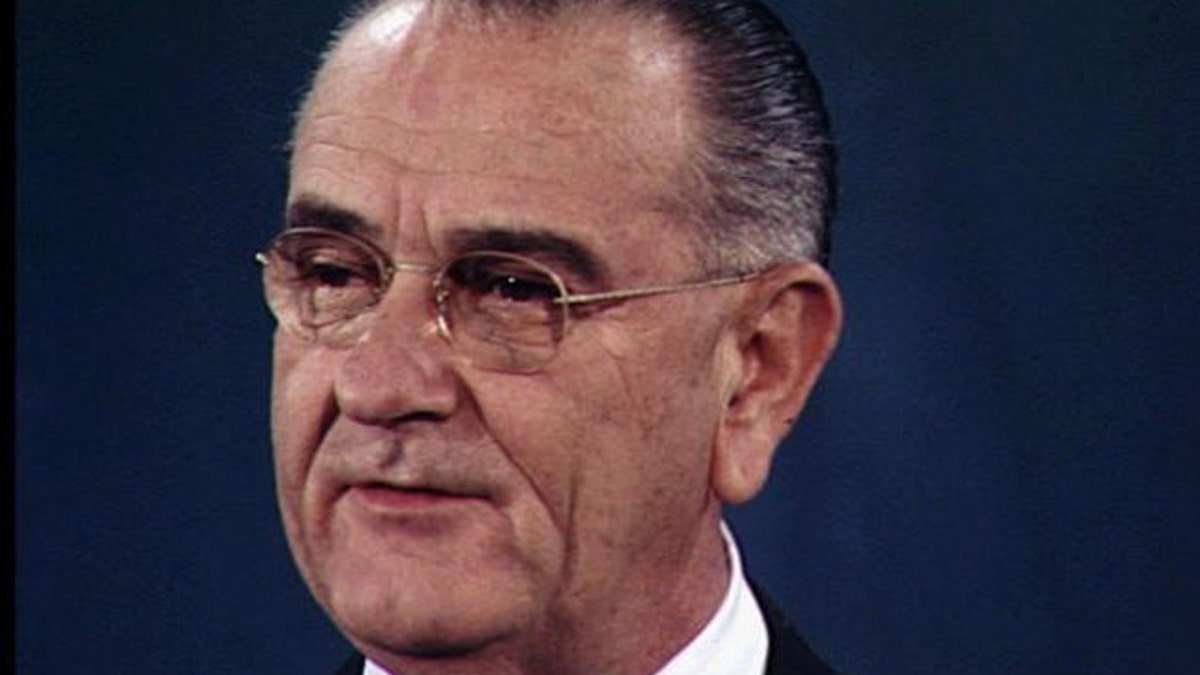

Fifty years ago today, President Lyndon Johnson delivered his first State of the Union address, promising an “unconditional war on poverty in America.” Looking at the wreckage since, it’s not hard to conclude that poverty won.

If we are losing the War on Poverty, it certainly isn’t for lack of effort.

In 2012, the federal government spent $668 billion to fund 126 separate anti-poverty programs. State and local governments kicked in another $284 billion, bringing total anti-poverty spending to nearly $1 trillion. That amounts to $20,610 for every poor person in America, or $61,830 per poor family of three.

[pullquote]

Spending on the major anti-poverty programs increased in 2013, pushing the total even higher.

Over, the last 50 years, the government spent more than $16 trillion to fight poverty.

Yet today, 15 percent of Americans still live in poverty. That’s scarcely better than the 19 percent living in poverty at the time of Johnson’s speech. Nearly 22 percent of children live in poverty today. In 1964, it was 23 percent.

How could we have spent so much and achieved so little?

It’s not just a question of the inefficiency of government bureaucracies, although the multiplicity of programs and overlapping jurisdiction surely means that there is a lack of accountability within the system. Rather, the entire concept behind how we fight poverty is wrong.

The vast majority of current programs are focused on making poverty more comfortable – giving poor people more food, better shelter, health care, etc. – rather than giving people the tools that will help them escape poverty. As a result, we have been successful in reducing the worst privations of poverty. Few Americans live with out the basic necessities of life, yet neither do they rise out of poverty. Moreover, their children are also likely to be poor.

Our goal should not be a society where people struggle along in poverty, dependent on government for just enough to survive, but rather a society where as few people as possible live in poverty, and where every American can reach his or her full potential.

It would make sense therefore to shift our anti-poverty efforts from government programs that simply provide money or goods and services to those who are living in poverty, to efforts to create the conditions and incentives that will make it easier for people to escape poverty.

And what would such a policy look like? We actually have a pretty solid idea of the keys to getting out of and/or staying out of poverty: (1) finish school; (2) do not get pregnant outside marriage; and (3) get a job, any job, and stick with it.

An effective War on Poverty, therefore, would reform our failed government school system to encourage competition and choice. High school dropouts are roughly three and a half times more likely to end up in poverty than those who complete at least a high school education, while few college graduates are poor for any extended period of time.

This doesn’t mean throwing more money at failing schools—we know that there is no correlation between education spending and achievement. Rather it means putting the interests of children before those of the teachers unions, and giving parents more control over where and how their education dollars are spent.

We should also recognize that too many of our current welfare programs actually subsidize out-of-wedlock birth. In 1964, just 6.4 percent of children were born out-of-wedlock. Today, nearly 41 percent are. Among African-Americans, more than 70 percent of children are born to single mothers.

Children growing up in a single parent family are almost five times more likely to be poor than children growing up in married-couple families. Roughly 63 percent of all poor children reside in single-parent families. Yet, as Charles Murray demonstrated years ago, the overwhelming body of research shows that the increased availability of welfare benefits is directly correlated with an increase in out-of-wedlock births. A successful War on Poverty would change these incentives.

Finally, if we want to win the War on Poverty, we should end those government policies — high taxes and regulatory excess — that inhibit growth and job creation. After all, the best route out of poverty remains a job.

Fewer than three percent of full-time workers are poor, compared to nearly 25 percent for those without a job. Even an entry level, minimum-wage job can be the first step on the road out of poverty.

Einstein is reported to have said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Throwing more and more money at more and more government programs doesn’t work. In the War on Poverty, it is time to try a different approach.