Over the summer, Americans were embroiled in fierce debates about NSA surveillance, Syria, and—of course—ObamaCare. Attorney General Eric Holder’s August 12th address on criminal justice reform, however, hardly made a blip on the national radar.

Observers who were surprised by this fundamentally misunderstand conservative views on criminal justice. Indeed, Holder himself quite possibly misunderstands conservative views on the subject. Three bits of conventional wisdom on this topic are completely wrong.

1. The conservative position on criminal justice is simply “lock ‘em up and throw away the key.”

Prominent conservatives like Jeb Bush, Newt Gingrich, and Ed Meese are committed to reducing the incarceration of many nonviolent offenders while also enhancing public safety through effective community corrections and law enforcement. After Holder’s August policy address, Grover Norquist and Richard Viguerie essentially asked, “What took you so long?”

Increasingly, conservatives argue that prisons are necessary to incapacitate violent and career criminals but sometimes grow excessively large and costly like other government programs.

In 2010, Americans spent $80 billion on corrections, a 150% increase since 1992. Over the last thirty years, prisons are the second-fastest growing component of state budgets (behind Medicaid). When conservatives talk about cutting the size and scope of government power, prisons are not exempt.

Conservatives appreciate the role that prison expansion has played in reducing crime, but they also recognize that incarceration has diminishing returns.

Criminologists credit increased incarceration with only 25-33% of the national drop in crime rates over the last two decades. For non-violent offenders who are not career criminals, incarceration is often counterproductive.

Citing recidivism rates of around 66% in some states, Newt Gingrich and Mark Earley observed: “If two-thirds of public school students dropped out, or two-thirds of all bridges built collapsed within three years, would citizens tolerate it?”

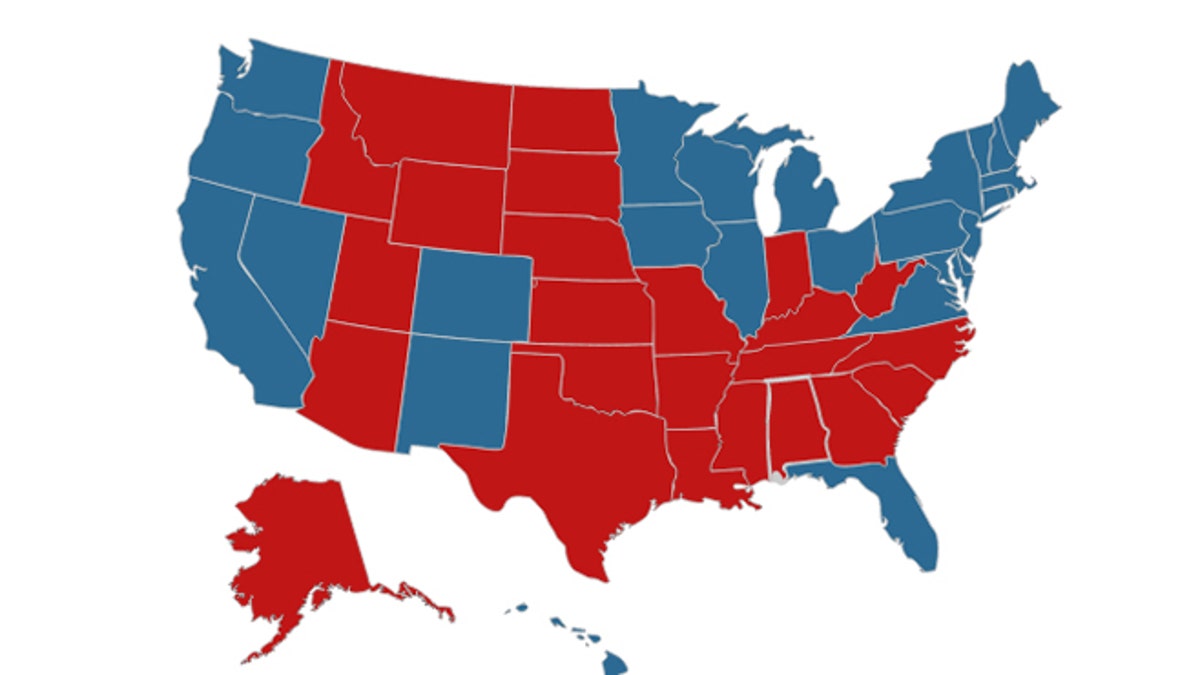

2. “Red states” are resistant to criminal justice reform.

The results of the 2012 presidential election. (FoxNews.com)

In just the last three years, conservative legislatures and governors in Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and South Dakota enacted major reforms to avert future prison growth that redirect some nonviolent offenders to drug courts, electronic monitoring, and strong probation with swift and certain sanctions to promote compliance.

In 2012 and 2013, Georgia’s conservative legislature and Republican governor, Nathan Deal, passed perhaps the nation’s most sweeping adult and juvenile correctional reform bills. In 2011, an important prison reform bill was signed by John Kasich, the Republican governor of Ohio.

Texas, in particular, is a national reform model. A 2007 legislative estimate projected that over 17,000 new prison beds, at a cost of $2 billion, would be needed in Texas by 2012. State legislators instead expanded community-based options like probation, accountability courts, and proven treatment programs—for a fraction of the cost of prison expansion.

Since Texas shifted towards alternatives in 2007, crime has dropped 25%, and Texas correctional facilities are thousands of beds below capacity. Since 2013, Texas has actually authorized three prison closings.

The leader of these reforms in the Republican-dominated Texas House of Representatives was a conservative named Jerry Madden, and it was Governor Rick Perry who signed the budgets and related legislation into law.

3. Conservative prison reforms are just a response to deficits and will be reversed once budgets are flush again.

(Reuters)

Prison reform makes fiscal sense, especially in the wake of a recession that severely tightened state budgets, but this is not the only motivation behind conservative reform efforts.

Texas, for example, began its reforms when it enjoyed a budget surplus.

Conservatives are principally concerned with public safety. Troubling recidivism statistics suggest that some low-level, nonviolent offenders who are incarcerated actually emerge from prison more dangerous than when they entered.

Conservatives want to ensure that non-violent offenders amenable to rehabilitation can resume their lives as law-abiding citizens, productive employees, and responsible parents.

They are particularly concerned about the effect of sentencing policies on families, the bedrock institution of society. Overwhelming social science evidence—and common sense—indicates that children of incarcerated parents are more likely to perform poorly in school, engage in juvenile crime, and be incarcerated themselves.

Addressing this problem means using prison less for some nonviolent offenders and using community supervision more—but tough supervision that requires offenders to provide restitution to their victims, get drug treatment, keep stable jobs, and support their families.