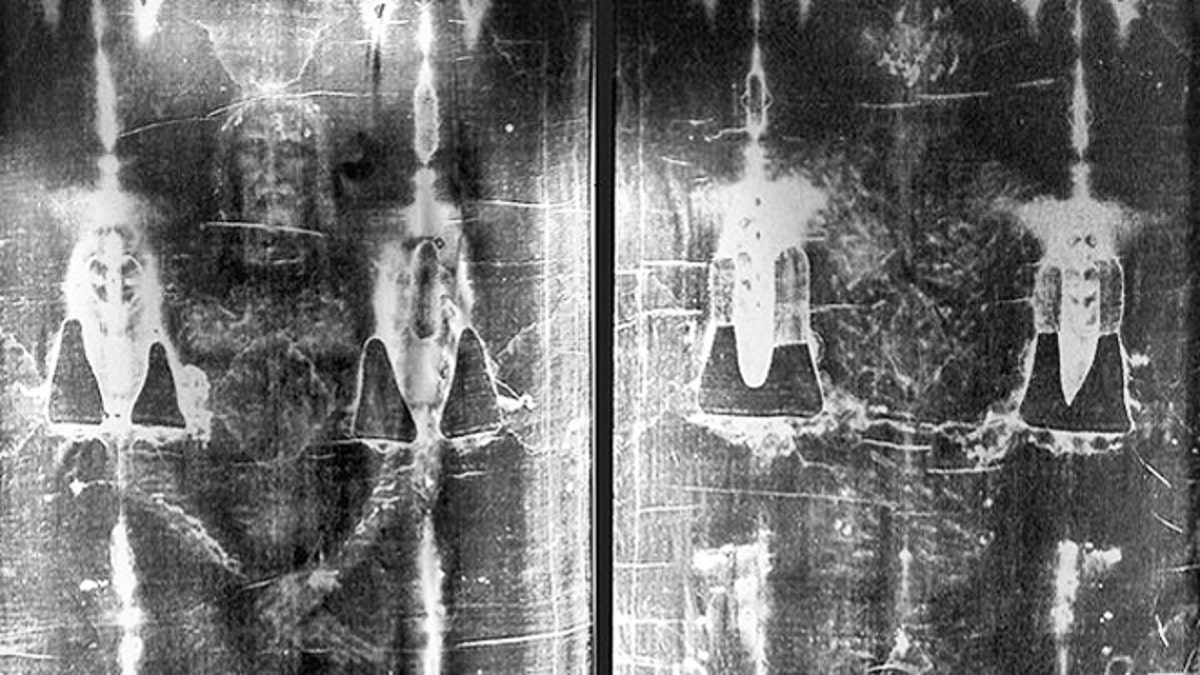

Full-length negative photograph of the Shroud of Turin.

For centuries, believers and skeptics have played tug of war with Shroud of Turin, a 14-foot strip of ivory-colored linen bearing the reddish-brown, bloodstained image of a crucified man. It’s the world’s most famous relic, revered by millions as the burial cloth of Jesus.

It’s also a lightning rod, sparking thorny questions of science and faith.

If the Shroud is genuine – 2,000 years old – can science prove its authenticity and miraculous origin (and thus prove the existence of God)?

If, on the other hand, it’s a clever forgery, how does science explain it – an image that’s highly detailed yet is so faint and barely-there that doesn’t even penetrate the surface of the fibers?

I pondered these questions while researching and writing "The Inquisitor’s Key," a crime thriller set in Avignon, France, the home of the Popes for most of the 14th century.

The book plays the ultimate game of forensic “What If?”: What if an ancient skeleton were found in Avignon’s Palace of the Popes, along with an inscription hinting that the bones were Christ’s? And what if a forensic facial reconstruction – an artist’s rendering of the face that once lived atop the skull – bore a striking resemblance to the face on the Shroud of Turin?

The scenario is surprisingly plausible, turns out.

The Shroud made its first indisputable appearance in 1357—not in Turin, Italy, but in Lirey, France, a town due north of Avignon.

The Middle Ages were the heyday of religious relics, too – artifacts (often human bones and body parts) intended to inspire devotion—and to draw pilgrims to the churches that possessed them.

The relics trade was brisk and bogus-laden. A partial list of medieval relics includes two heads of John the Baptist; three corpses of Mary Magdalene; six—count ‘em, six—foreskins from the circumcised penis of the baby Jesus; 30 “holy nails” used in the crucifixion; and enough wood from the True Cross to build a small armada.

The Shroud is the one relic that seems to defy modern skepticism and science – seems to thrive on them, in fact.

Its reputation got a big boost from science in 1898, when a glass-plate photographic negative revealed an eerie black-and-white face, far more dramatic and lifelike than the faint image on the cloth itself. Was the negative high-tech proof of an age-old miracle? Or was it a primitive precursor to Photoshop: image processing that retouched reality in a powerful way?

The Shroud is no newcomer to controversy. In the 14th-century, a French bishop wrote the pope in Avignon to warn him that the relic was a cunning fake. And the Vatican itself has never asserted that the Shroud is genuine. But ever since that 1898 photographic negative, believers (including some scientists) have sought more high-tech proof of the Shroud’s miraculous nature.

Occasionally that strategy has backfired. In 1988, tiny snippets of the Shroud were sent to three scientific labs for carbon-14 dating. All three labs reported that the fabric was only seven centuries old.

Disappointed devotees – who’d counted on the C-14 tests to prove that the Shroud was 2,000 years old – suddenly scrambled to attack the testing. The fabric samples, they charged (and still insist), were cut from an “invisible” repair made in the 1500s.

Even more credulity-straining is one scientist’s assertion that the image was created, at the moment of Jesus’s resurrection, by an intense flash of radiation (a hypothesis later dismissed as impossible even by other scientists who believe in the Shroud’s authenticity).

Skeptics can sound equally absurd. Shortly after Dan Brown’s bestselling novel "The Da Vinci Code," a sensationalist book claimed that the man on the Shroud is actually Leonardo Da Vinci, posing for the world’s first primitive photograph (this despite the fact that Leonardo wasn’t yet born in 1357, when the Shroud debuted.)

But the Shroud’s mysterious image has a simple explanation, according to two credible investigators: professional skeptic Joe Nickell, and Dr. Emily Craig, a forensic anthropologist with years of experience as a medical illustrator.

Working independently, Craig and Nickell have both demonstrated that a medieval artist could have created the image with materials and techniques that were common in the 1300s.

How?

By applying a faint dusting of red ochre (a pigment made from ferrous oxide – an artist’s version of rust) to the linen.

Red ochre and dust-transfer were used 30,000 years ago, to make cave paintings in Spain and France, so it’s reasonable to think that a 14th-century artist in France could have used them. What’s more, a respected microscopist, Dr. Walter McCrone, detected red ochre in the image on the Shroud; he also found vermillion (a brighter red pigment) in the Shroud’s “bloodstains.” But the work of McCrone, Craig, and Nickell has been ignored or shouted down by those who disagree with them, or who don’t want to hear what they have to say.

I don’t expect "The Inquisitor’s Key" to settle the centuries-old debate about the Shroud’s authenticity. And maybe that’s just as well. Maybe, by provoking thought and discussion about faith and science – about the miraculous and the mundane – the Shroud is doing exactly what its creator intended.

Jon Jefferson is a New York Times bestselling writer, whose new crime novel, "The Inquisitor’s Key," (HarperCollins 2012) scrutinizes the Shroud of Turin through a forensic lens.