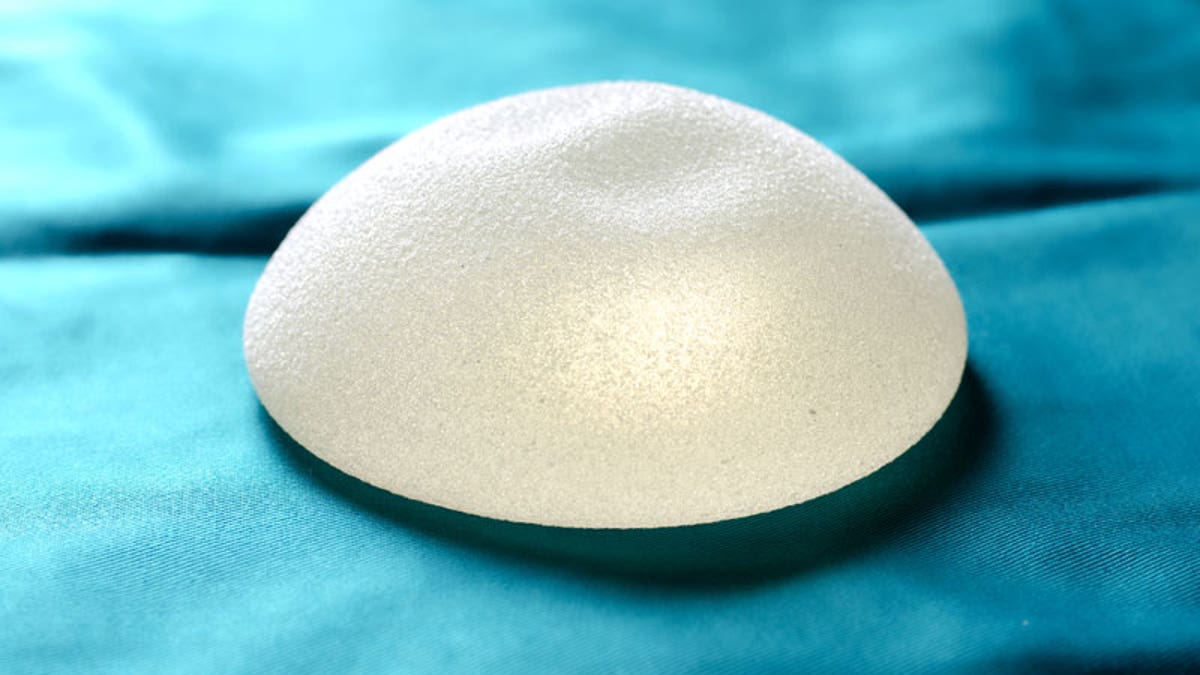

Women with breast implants are at increased risk of developing a rare type of cancer, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said. (iStock)

Women with breast implants are at increased risk of developing a rare type of cancer, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said. But how do these implants increase the risk of cancer?

On Tuesday (March 21), the FDA said that, in light of new data, the agency now recognizes that a rare type of cancer called anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) can develop after a person receives breast implants. ALCL is not breast cancer; rather, it is a type of lymphoma , which is a cancer of immune system cells, the FDA said in a statement. In the cases that were reported to the FDA, the cancer typically occurred in the scar tissue around the implant, the agency said. So the cancer occurs in the immune system cells around the breast implant, but not in the breast tissue cells themselves.

From June 2010 to Feb. 1, 2017, the agency received more than 350 reports of this cancer linked to breast implants, including nine cases of patients who died from the cancer. Some of the women in these reports were diagnosed with the cancer as early as 1996.

Still, the risk of this cancer is low; one study from the Netherlands estimated that there were about one to three cases of ALCL per 1 million women with implants per year. In the United States, about one in 500,000 women is diagnosed with ALCL each year, although the incidence of this cancer specifically among U.S. women with breast implants is not known, according to the FDA.

More From LiveScience

"All of the information to date suggests that women with breast implants have a very low but increased risk of developing ALCL compared to women who do not have breast implants," the FDA said. [ 7 Plastic Surgery Myths Revealed ]

Exactly how breast implants might cause cancer is not known. But studies have suggested that chronic inflammation — which is considered a precursor of many cancers — may play a role in these cancers, said a 2016 paper published in Aesthetic Surgery Journal . Some studies have found markers of chronic inflammation in the scar tissue around breast implants, suggesting that an immune response to the implants might trigger ALCL, the paper said.

Another idea is that the bacteria that colonize the area around the implant might trigger an immune response that, in turn, increases cancer risk. A 2016 study examined the community of bacteria around tumor samples in people with ALCL that was linked to breast implants. The study found that these bacteria were significantly different from the community of bacteria around samples from people with breast implants who did not develop cancer.

Studies have also found that ALCL occurs more commonly in women who receive breast implants that have a textured surface, compared to people who receive implants that have a smooth surface. Of the 231 reports of this cancer that the FDA received that included information about the implants' surface, 203 cases involved textured implants, while 28 involved smooth implants, the FDA said.

It's not clear why the risk of this cancer would be higher for those who get textured implants, but the body appears to react differently to textured implants than to smooth ones, The New York Times reported .

The median time that elapsed between the implant surgery and the cancer diagnosis was seven years, but in at least one case, it was 40 years, the FDA report said. Women who developed the cancer ranged in age from 25 to 91, the report said.

The FDA said that people who are considering getting breast implants should talk with their doctors about the benefits and risks of textured implants versus smooth implants. People who already have breast implants should continue to see their doctors for follow-up care as they otherwise would, the FDA said.

The agency stressed that this cancer is rare, and so removing breast implants in people who don't have symptoms related to ALCL is not recommended. Patients should contact their doctors if they notice pain, swelling, or any changes in or around their breast implants, the FDA said. Many cases of this cancer resolve after removal of the implant and the tissue surrounding it, according to a 2014 paper in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Original article on Live Science .