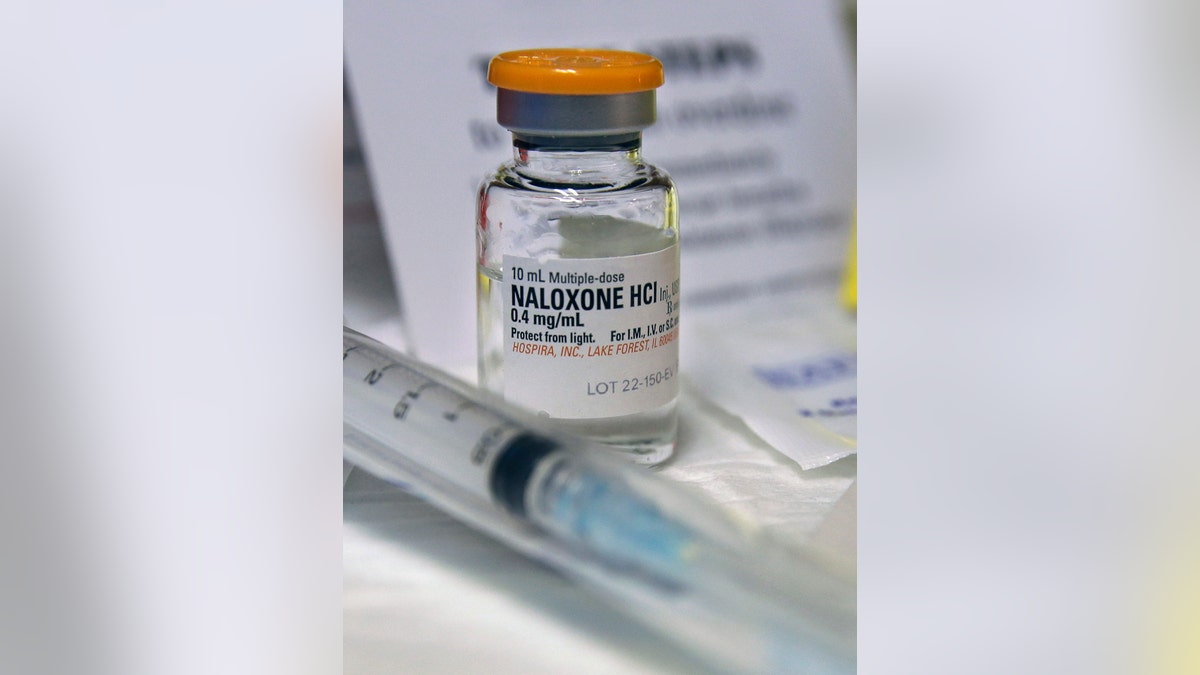

(AP Photo/Mel Evans,file)

NEW HAVEN, Conn. – It’s been 10 months since pharmacist Edmund Funaro Jr. completed a training program to be able to prescribe the opiate overdose reversal medication naloxone, and yet he has not written one prescription for the drug.

“I haven’t had anyone come in and ask for it,” Funaro said. “I’ve dispensed a few for people who got prescriptions from their doctors, but as far as someone coming in and asking for it, there’s been none.”

Funaro is the director at Visels Pharmacy, at Dixwell Avenue and Bassett Street, just a few blocks away from where several people recently overdosed on the potent synthetic drug fentanyl. They were just a few of the 17 opioid overdoses in the city June 23 that left three people dead and forced the city into a health emergency.

The lives of the victims that did survive were saved by first responders who used naloxone, often referred to by the brand name Narcan, to treat the overdoses.

Last July, state legislation was passed that allowed pharmacists who have been trained and certified, like Funaro, to prescribe Narcan to users of both legal and illegal opioids, their caregivers, and loved ones.

Michelle Seagull, deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection, said the program is growing. Pharmacies are one of the components of health care that people have the most contact with, and while doctors can write prescriptions to naloxone, too, giving pharmacists the ability to prescribe the drug made it more accessible.

“It’s just a place people are more comfortable with to be able to pick up a product,” Seagull said. “If you have to go to the doctor, you have to make an appointment, there’s that added barrier to do it. There’s a lot more pharmacists available than doctors’ offices. This is a product maybe people don’t need for themselves so they may not even need the doctor.”

Funaro is one of more than 700 pharmacists in the state that have received certification.

“If a person did come in to my store and asked for Narcan I have the kits here ready. I would sit down with them and teach them how to use it, answer any questions they have,” Funaro said. “That’s the most important piece of this; we’re not just giving the drug, we make sure they know how it works and how they can save a life with it.”

There are several options of naloxone available, but Funaro recommends the Narcan nasal spray for families because he said it is more user-friendly, especially in emergency situations. Health professionals across the state encourage anyone at risk for having or witnessing a drug overdose to carry Narcan with them at all times, the same way people with asthma would carry an EpiPen.

Connecticut’s Insurance Commissioner Katharine Wade sent a reminder to health insurers last month that FDA-approved opioid abuse deterrent drugs, like Narcan, associated with drugs prescribed for pain management purposes, must be covered if medically necessary.

“Individuals should check their own insurance policies because there could be a co-pay associated, or cost-sharing, but we’re supporting that they should have direct access to Narcan,” Wade said.

However, the reality is that many people are not taking advantage of the pharmacy prescription service.

Allison Fulton, of the Housatonic Valley Coalition Against Substance Abuse, said she believes the lack of participation from the public comes from misunderstanding, misconceptions, and also being unaware of the drug’s availability.

“Family members don’t even know that they are allowed to carry it. We’re trying to raise awareness about that as long as the pharmacist is trained, you can get Narcan directly from the pharmacist,” Fulton said.

The statewide coalition meets monthly and has been trying to raise awareness by having individuals in the group reach out to their own communities.

“We’re doing what we can at a very grass-roots level,” she said. “We’re still in that stage of building up the best practices.”

A doctor in the group, according to Fulton, even initiated a “co-prescription” program in his own office. When the doctor prescribes opioids to patients, he also informs them of the possibilities of overdose, offers to prescribe them the naloxone and the training that goes along with it.

“A very low percentage of people said ‘yes’ and went through the training,” Fulton said. “We’re still finding that even patients themselves are still leery of the process.”

All of patients suffering from addiction and their families are offered Narcan prescriptions at the South Central Rehabilitation Center, 232 Cedar St., according to Program Director Benjamin Metcalf. While some people accept the prescription, there are still those who are not comfortable going to the pharmacy to obtain Narcan.

“There’s still a stigma associated with it. They’ll get these prescriptions from the doctor, but they won’t go to the pharmacy to get it because they don’t want people to think they have a drug problem,” Metcalf said.

Funaro said when he has a patient come in for a prescription, that’s the last thing on his mind.

“I’m not here to judge people. Whether you’re a drug use or not, the more Narcan we can get in people’s hands the more lives we can save, that’s the bottom line,” Funaro said.

The pharmacist said he is well aware that there are people in the neighborhood suffering from drug addiction and that’s why he thought it important to be trained. That’s also why he sells syringes in his store, with the goal of reducing the spread of HIV and hepatitis C among drug users. While Funaro said some people think offering Narcan and needles encourages drug use, he sees it as a public service.

“You have to serve the people where you’re located. We know what people are doing, and you may not agree with that lifestyle, but as a health professional, you have to make sure they are doing it as safe as possible and with the least amount of harm to the community overall,” Funaro said.

Fulton said people who oppose the drug have also said drug users will see it as a safety net, that they can throw caution to the wind and use as much opioid as they want and still have the Narcan just in case of an overdose.

“It’s not about that. Our whole thing is to get people to recovery at some point in their lives. It might take them several overdoses and several Narcans to get them there, but at least they’re still alive and able to make the decision to turn things around, no matter how long it takes. That’s what’s important,” Fulton said.

She and other healthcare professionals like Metcalf and Funaro said there is still a lot of work to be done in the battle against drug addiction, and giving access to Narcan is just one piece of it.

“We’re really trying to get people to see that it’s very safe, it’s important to have, and it can give someone another chance for recovery,” Fulton said. “We have a long road ahead of us and we need people to be informed and to take action.”