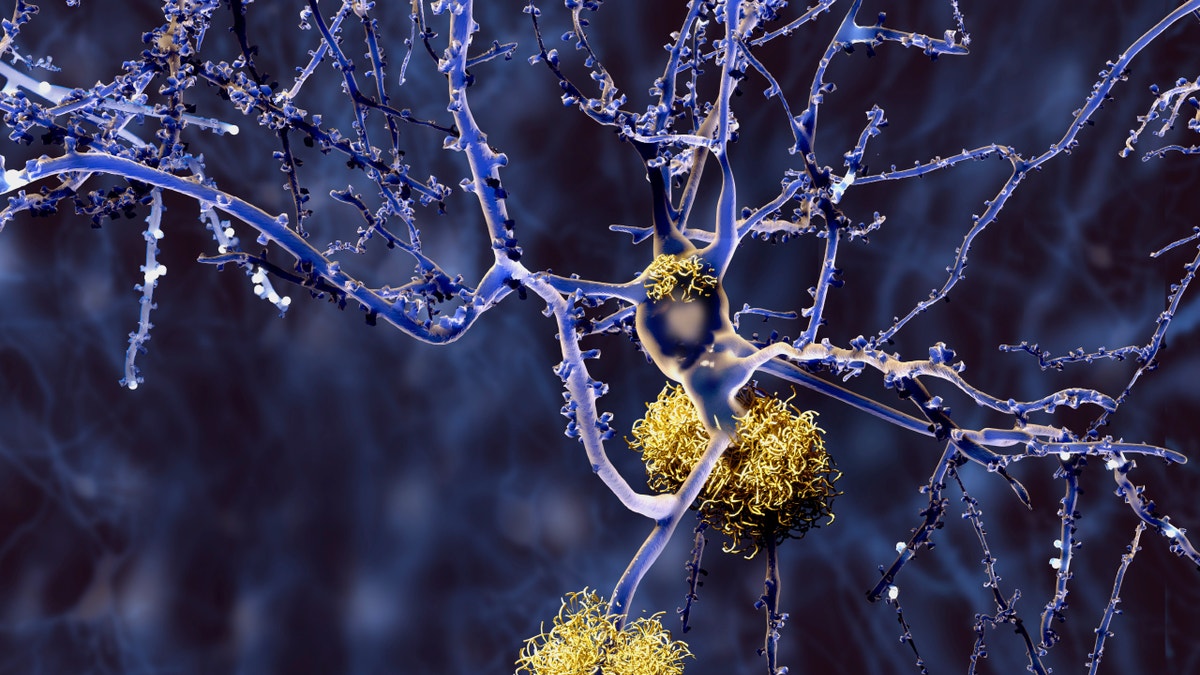

An image of amyloid plaques. (iStock)

Alzheimer’s remains one of the costliest yet most mysterious conditions in the United States, where an estimated 5.1 million Americans are living with the incurable, progressive disease. But researchers at The Rockefeller University have found that manipulating a protein pathway linked with Alzheimer’s helped improve memory impairment in mice— a finding that offers hope for new treatment in humans. Memory loss is the hallmark symptom of the disease.

Scientists with the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University used a complex set of imaging technologies and experiments to identify an early trafficking protein pathway (COPI) that affects amyloid precursor protein (APP), which precedes the formation of amyloid plaques. Previous research on Alzheimer’s have targeted this plaque, but scientists haven’t successfully identified a way to halt its progression. There is currently no cure or effective treatment for the disease.

Through two separate studies published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences— involving biochemical models and an animal model— researchers observed that manipulating this pathway to moderate COPI helped reduce amyloid plaques, resulting in improved memory function in mice.

“These findings are significant as they provide further explanation of the creation of amyloid plaques, a primary symptom of the disease, and that the manipulation of this pathway leads to improvement of some memory impairments, which can lead to future Alzheimer’s treatments that slow the progression of the disease,” Nobel Laureate Dr. Paul Greengard, director of The Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research, said in a news release. The Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research, a nonprofit that’s aiming to find a cure for Alzheimer’s, funded the study.

Study author Marc Flajolet, an associate professor in Greengard’s lab, told FoxNews.com that APP must go through several processing steps to release the toxic peptides amyloid beta, which then aggregates and forms the plaque that’s problematic in Alzheimer’s disease. He said his team’s findings differ from previous studies on this progression because they focused on interfering with the pathway at an early rather than late stage.

“Most studies carried out till now were targeting the very late steps of this whole multi-step process, and we thought, ‘Let’s look at the very early steps and maybe we’ll have more chances to modulate this pathway,’” Flajolet said. “We found that was not only the case for amyloid plaques, but that it also worked in this animal model for memory.”

A promising improvement by targeting COPI earlier rather than later is now, potential treatments in clinical trials may be less inclined to induce cancer— an effect that some studies suggest may occur during later interference with the pathway, he said.

“[Researchers] were solving one problem and introducing cancer on the other side,” Flajolet said. “We hope with this new approach we won’t have those kinds of problems, or at least they won’t be as bad or as strong.”

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia and according to the Alzheimer’s Association, the number of new annual Alzheimer’s cases and other dementias is projected to double by 2050. The estimated value of care for patients, $217.7 billion in 2014, is expected to nearly triple by 2050.